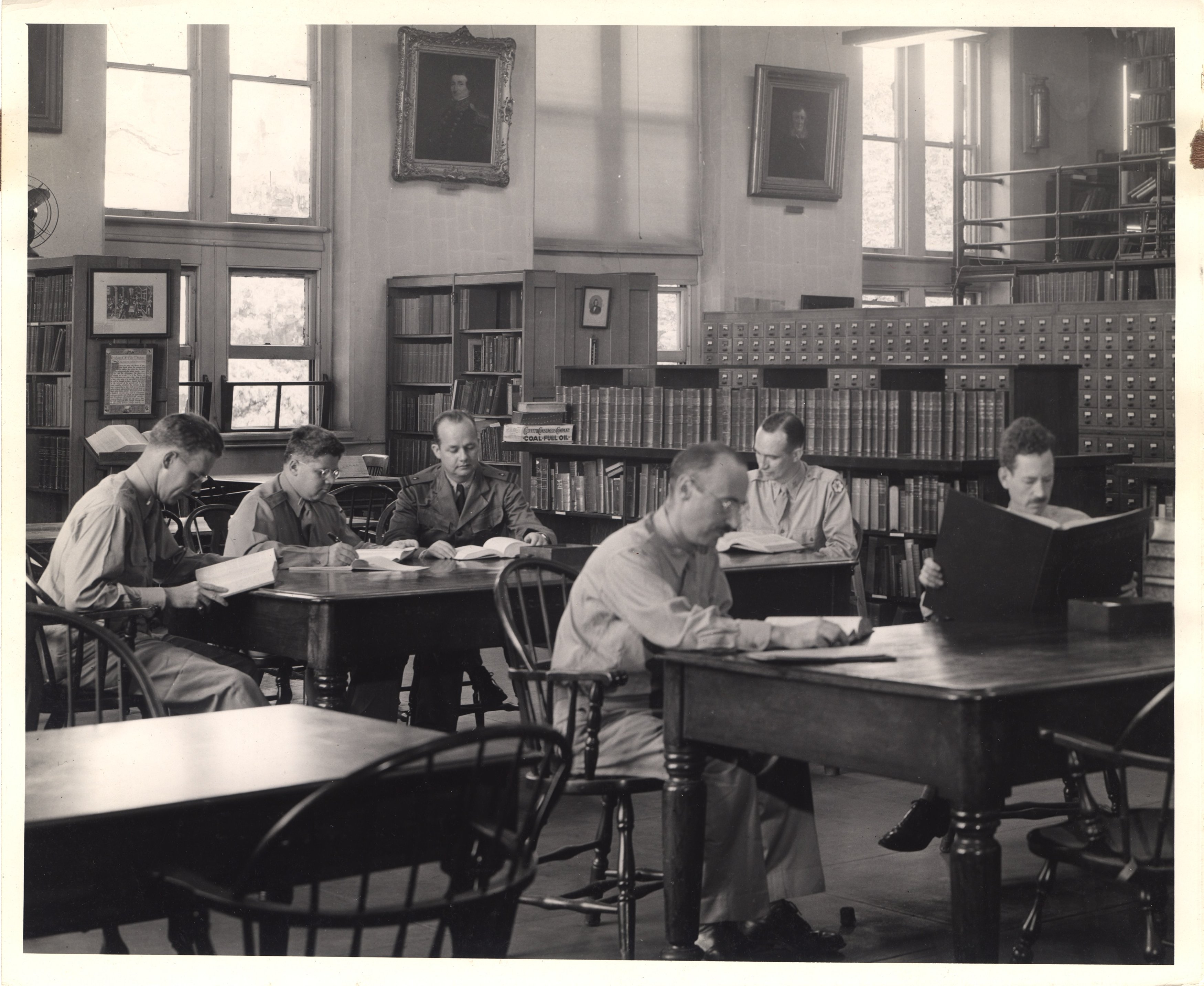

Image: Medical men use the library reading room, 1940. Retrieved from the National Library of Medicine.

Benjamin Gagnon Chainey

Reminiscence of Georges Canguilhem:

A review of l’Homme sans fièvre, by Claire Marin

Perhaps is there a need to think the future of medicine

in a new horizon, not so much that of healing, but that of diminishing

human suffering [1].

Sometimes, Western medicine exacerbates suffering as it strives to heal. This is the paradox French philosopher and writer Claire Marin uncovers in l’Homme sans fièvre – the title may be roughly translated as The Man Without Fever. The author, a researcher at the Georges Canguilhem Center for the History and Philosophy of Science, in Paris, interrogates the kind of care we could provide as an alternative to our society’s obsession with healing. Marin seeks to unravel the myth of “perfect health” that burdens contemporary medical and ethical discourse on care. She asks: ‘Can we cure without healing?’ (CM, p. 9).

Marin’s Man Without Fever is afraid of death, because he has forgotten how to suffer from the inevitable violence of disease, violence of life [2]. He dreams of becoming the ‘man without disease’ (CM, p. 21). As she tends to him, Marin attempts a remedy: a philosophical and literary essay that combines the resilient empathy of her autofiction Hors de moi [3] (‘Out of Myself’) with a critique of the almighty medical and scientific postures that refuse to give up on the project of healing at any cost, even in light of its persistent limitations in the cases of cancer, Alzheimer’s, or AIDS, to name a few. Marin dismantles the well-establish equation between care and healing. In doing so, she lays out some ‘directions for a new biopolitics’ (CM, p. 19). These, she suggests, are twofold: first, we must ‘be attentive to human complexity as much as to more technical medical skills’; second, there is a need to ‘respond in a more appropriate and efficient manner to the essential question of human suffering’ (CM, p. 18).

To materialize this ‘truly political ambition’ (CM, p. 18), Claire Marin’s Man Without Fever must first agree to abandon the ‘new utopia’ of healing. This utopia drives the over-medication of the social body as it promises a ‘living body [that] is but strength, reproduction and growth’ (CM, p. 21). However, it also leaves aside ‘neglected or invisible forms of care’ (CM, p. 65). Marin, in contrast, suggests accepting and, more importantly, better accompanying vulnerability, instead of waging a therapeutic war against it. In doing so, she complements the work of philosopher Georges Canguilhem, who in the middle of the 20th century published pioneering work in the philosophy of science and medicine. In his Writings on Medicine, he notes:

Contemporary medicine is founded, with an efficacy we cannot but appreciate, on the progressive dissociation of disease and the sick person, seeking to characterize the sick person by the disease, rather than identify a disease on the basis of the bundle of symptoms spontaneously presented by the patient [4].

Claire Marin takes as a springboard Canguilhem’s critique of the patient’s reduction to his or her disease, and extends it to interrogate the relationship between bodies and suffering. She also opens up the scene to the healthy bodies that attempt to cure suffering bodies, as well as to the bio-psycho-social and cultural elements that make the relationship complex. Marin therefore displaces the critical accent from the ‘suffering body’ to the ‘healthy individual’s relationship to their body’ (CM, p. 31). This displacement serves as a discomforting reminder to the healthy, who prefer eluding their own rapport to the Other’s suffering, and avoid experiencing it.

Marin builds on Sartre’s ‘disgust of the body’ [5] (CM, p. 32) to flip around the current consensus that places illness as the source of suffering. Indeed, ‘medical orthodoxy’ is torn between ‘a cult of the body and a hatred for the organic body’ (CM, p. 32). The disgust for the body, and for nature more broadly, is a ‘cultural disgust, construct[ed] over the last decades’ (CM, p. 33), which means that it is also through culture that it may be overcome. As Canguilhem notes, already in the Middle Ages, illness was culturally embedded: “naming the disease would aggravate its symptoms, because the disease entailed social exclusion as much as organic consumption [6].”

It is therefore through medical humanities, which are ‘extensions of the field of care’ (CM, p. 65), that we may hope to find a different kind of remedy to our relations to suffering. For Marin, it is indeed in philosophy and literature that we may find a ‘pedagogy of suffering that would allow understanding, and perhaps experiencing, its violence’ (CM, p. 14). She therefore offers a welcome counterpoint to Georges Canguilhem’s question: “Is a pedagogy of healing possible? [7]”

Yet, as we follow Claire Marin’s argument, it seems the integration of medical humanities into medical and ethical debates has yet to permeate the political field. Marin suggests a few reasons for this difficulty: for instance, the current temporal compression of care attributable to hospital bureaucracy – which is an absurdity, according to Marin – and the contemporary mantra of the patient’s autonomy, as it ignores that autonomy is precisely what may be at stake in suffering, poses ‘epistemological obstacles’ [8] (CM, p. 71). Marin’s argument rests on the metaphor of the ‘actor’s performance that must be directed,’ as an alternative to autonomy’s domination of the care relationship:

The idea that patients participate to a care process is perhaps more just, according to their desire and their capacity to do so. Like actors, in any case – and this is perhaps where the metaphor operates – they must be directed, and like actors, they are attributed a role that they have not chosen, and, in the circumstances, they could have done without (CM, p. 85).

While Marin’s essay stops at the threshold of the political, it also introduces elements that suggest a few avenues on how to take that last step. The most encouraging, perhaps, consists in engaging in a genuinely interdiscursive and interdisciplinary analysis of the discourses that interact around the question of suffering. Indeed, by borrowing, for example, from interdiscursivity theories (such as canonical Bakhtin, Eco and international followers), and the very rigorous (and primarily applied) field of Bioethics, one could push further Marin’s illustrative use of literary works – for example her references to J. M. Coetzee – to ask what precise conduits connect philosophy and literature in their joint attempts to offer a re-articulation of medical and ethical discourses.

The political, in that sense, may lie exactly in those efforts to re-articulate multiple voices and in the toil of finding passageways between discourses. Only then can philosophy and literature hope to offer medicine and ethics an opportunity to learn a different language besides that of conventional healing. For, as George Canguilhem tells us: “To learn to heal is to learn the contradiction between today’s hope and the defeat that comes in the end—without saying no to today’s hope. Is this intelligence, or simplicity? [9]” Claire Marin reminds us that ‘we still have a lot to learn. The first lesson being undoubtedly to learn not to heal’ (CM, p. 185).

Notes and references

[1] Claire Marin (2013). l’Homme sans fièvre. Paris: Armand Colin. p. 15. (Hereafter referred to as CM in the text. I translate all the quotes from Claire Marin)

[2] Claire Marin (2008). Violences de la maladie, violences de la vie. Paris: Armand Colin. This book was awarded in 2010 with the Prix Éthique et société Pierre Simon.

[3] Claire Marin (2008). Hors de moi. Paris : Éditions Allia. Awarded with the French Académie de médecine’s literary prize in 2008.

[4] Georges Canguilhem (2012). Writings on medicine. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 35.

[5] See Sartre’s Nausea. Marin does not fully explore the notion’s existential underpinnings, though.

[6] Georges Canguilhem (2012). Writings on medicine. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 59.

[7] Ibid. p. 53.

[8] According to care theories, including recent renewal efforts by philosopher Joan Tronto.

[9] Georges Canguilhem (2012). Writings on medicine. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 66.