Anna Fenton-Hathaway

When Ursula Le Guin’s 1973 “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” appears on a Science Fiction and Bioethics syllabus, what should medical students think? First, they might reasonably ask, is this even science fiction? bioethics?

“Omelas” has been called a “psychomyth” by its author (254); a “descriptive work of philosophical fiction” by Wikipedia; and by a colleague of mine—aptly and not at all unadmiringly—“ghastly.” It is an ingenious nine pages.

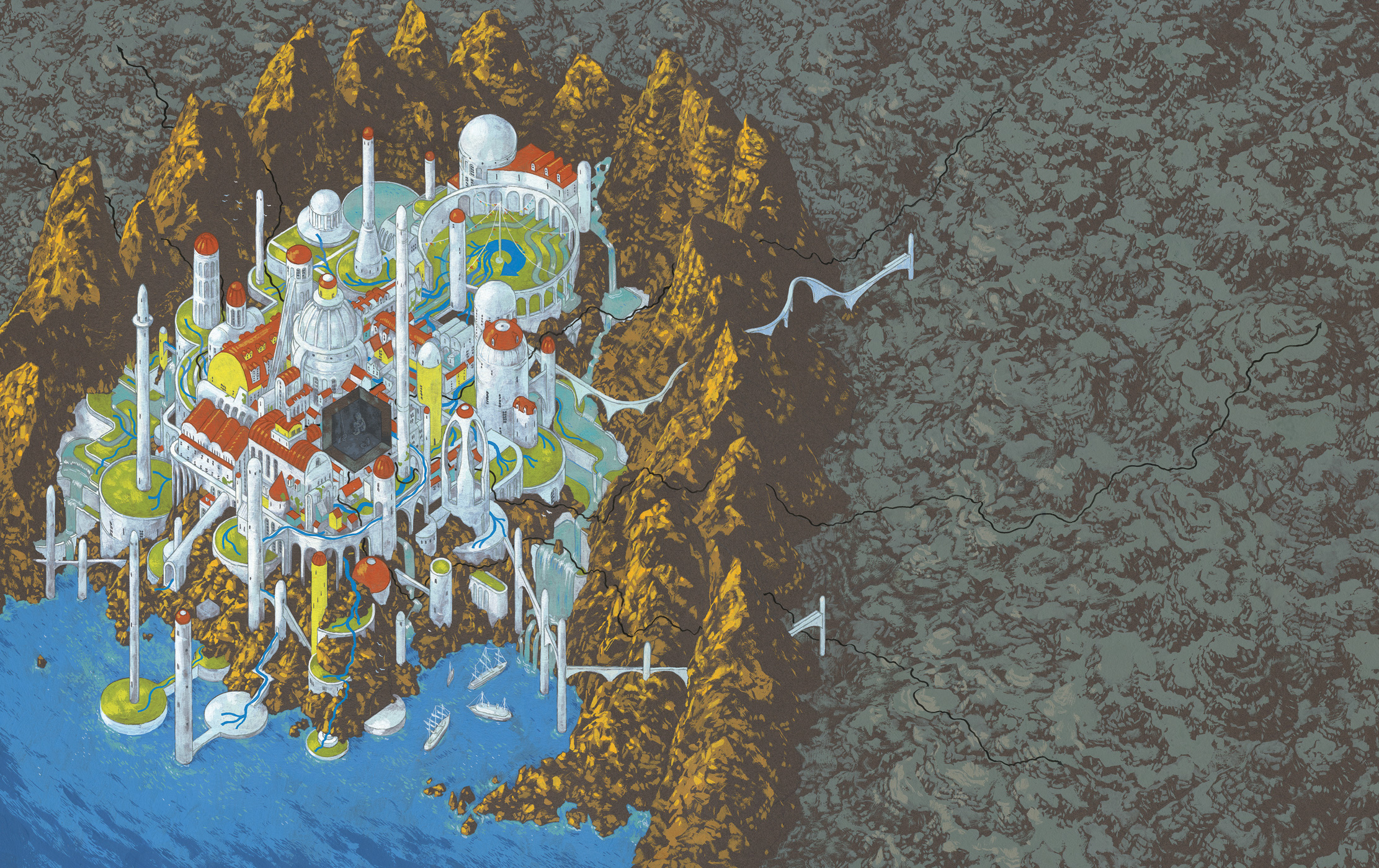

The premise: Omelas is a vaguely medieval but not-at-all-primitive society filled with “mature, intelligent, passionate adults” whose lives are happy ones. “[T]hese were not simple folk,” the narrator insists, “not dulcet shepherds, noble savages, bland utopians. They were not less complex than us.” To convince the reader of this, the narrator packs in unusual details—the society has music and Festivals, but (may) also have “floating light-sources,” subways, and central heating. Staple figures like merry women and master artisans appear, but also geography with the mark of specificity (“Eighteen Peaks,” the “Green Fields”). Eventually, the narrator seems to cry uncle. “Perhaps it would be best if you imagined it as your own fancy bids, . . . for certainly I cannot suit you all” (256–57).

To combat the reader’s skepticism—“Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy? No?”—the narrator asks to describe “one more thing.”

In Omelas there is also a child kept underground, against its will. The room is dark, musty, cramped; in one corner there are “a couple of mops, with stiff, clotted, foul-smelling heads, stand[ing] near a rusty bucket. . . [The child] sits haunched in the corner farthest from the bucket and the two mops. It is afraid of the mops. It finds them horrible. It shuts its eyes, but it knows the mops are still standing there; and the door is locked; and nobody will come.” (The narrator uses “it” to describe the nine-year-old because, she says, the child “could be a boy or a girl.”) Food and water are intermittently brought to the room, but the child “sits in its own excrement continually” (259–60).

So why don’t any of Omelas’s mature, passionate adults—or even the adolescents who are brought to see the child when they are eight or nine themselves—free the child? Even as it is calling out, wretchedly, “Please let me out. I will be good!”? Because, the narrator tells us, “they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery” (260). The ones who cannot make themselves “understand” this perverse paradox are those named in the title; they will not abide this utilitarian limit case, and so they walk away.

My concerns about teaching this? That neither complicity nor exile gets the child out of the basement. That the sophisticated student (and her instructor) may know that the fact of suffering, of exploitation, of ghastly inequities indeed, cannot be denied—but what then is to separate that “knowledge” from acquiescence, or acceptance? (“Suffering is inevitable, especially for others…”) Is this a worldview that should be decked out in such vivid, potent form for future physicians? Or to people who might one day weigh in on concrete questions about resource allocation, health care access, or biomedical ethics?

* * *

Le Guin has acknowledged her debt to different iterations of this notion in literature (Dostoyevsky’s 1879–80 The Brothers Karamasov) and in philosophy (William James’s 1891 address, “The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life”), that the fulfillment and happiness of some is predicated on others’ suffering.

I’ve quoted so much of “Omelas” to show how deftly the author has taken what was once, in those earlier contexts, a question—if you could secure happiness for yourself and some large number of others by subjecting an innocent to “abominable misery,” would you?—into a flexible, timeless given. After all, the only time the narrator is unequivocal (no “or” statements, no “as you like it”s) is when she insists that were the child to be gently led out of its prison, bathed, held close in someone’s arms, “in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms” (261; italics mine).

Compare that proclamation to The Brothers Karamasov, where Ivan puts the matter to his devout brother Alyosha this way: “Tell me yourself, I challenge you—answer. Imagine that you are creating a fabric of human destiny with the object of making men happy in the end, giving them peace and rest at last, but that it was essential and inevitable to torture to death only one tiny creature—that baby beating its breast with its fist, for instance—and to found that edifice on its unavenged tears, would you consent to be the architect on those conditions? Tell me, and tell the truth” (269).

Tell me, I challenge you, answer, would you consent? Those are the phrases in Ivan’s thought experiment. In Le Guin’s, consent is a foregone conclusion. The ones who remain in Omelas “feel anger, outrage, impotence, despite all the explanations. They would like to do something for the child. But there is nothing they can do. . . . Their tears at the bitter injustice dry when they begin to perceive the terrible justice of reality, and to accept it. Yet it is their tears and anger, the trying of their generosity and the acceptance of their helplessness, which are perhaps the true source of the splendor of their lives. Theirs is no vapid, irresponsible happiness. They know that they, like the child, are not free. They know compassion” (261–62).

The transformation from open question to inescapable fact is disturbing, provocative, and resonant. It recalled for me a scene in Mountains Beyond Mountains, Tracy Kidder’s book on Paul Farmer and Partners in Health, when Farmer chides Kidder for musing incorrectly that Haiti and Paris occupy “parallel universe[s].” Oh, Farmer inquires sharply, so there’s “no relationship between the massive accumulation of wealth in one part of the world and abject misery in another”? (218). Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, too, links the violence Coates experienced as a boy in Baltimore to the simultaneous comfort of suburban white youth: “Fear ruled everything around me, and I knew, as all black people do, that this fear was connected to the Dream out there, to the unworried boys, to pie and pot roast, to the white fences and green lawns nightly beamed into our television sets” (28–29). But while both books convey powerful descriptions of suffering, they do so specifically, in non-mythic time, with an eye to historical causes and with ample attention to the responses (intellectual, medical, political, personal and collective) to injustice. Maybe the answer, then, is to teach these other incarnations alongside Le Guin’s parable. Maybe we’ll start with W. S. Merwin’s “Thanks.”

The image above is Andrew DeGraff’s illustrated map of “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” from Plotted: A Literary Atlas (Zest Books, 2015).

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2015.

DeGraff, Andrew. Illustrated map of “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” In Plotted: A Literary Atlas (Zest Books, 2015). http://www.andrewdegraff.com/plotted/.

Dostoyevsky, Fyodor. The Brother Karamasov. Translated by Constance Garnett. New York: Lowell Press, 1912. Project Gutenberg eBook released February 12, 2009. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28054/28054-h/28054-h.html.

Kidder, Tracy. Mountains Beyond Mountains: The Quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, A Man Who Would Cure the World. New York: Random House, 2004.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Wind’s Twelve Quarters and The Compass Rose. London: Orion Publishing, 2015.

Merwin, W. S. “Thanks.” From Migration: New and Selected Poems (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2007). https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/57937/thanks.

Wikipedia. “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” Revised November 20, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ones_Who_Walk_Away_from_Omelas.