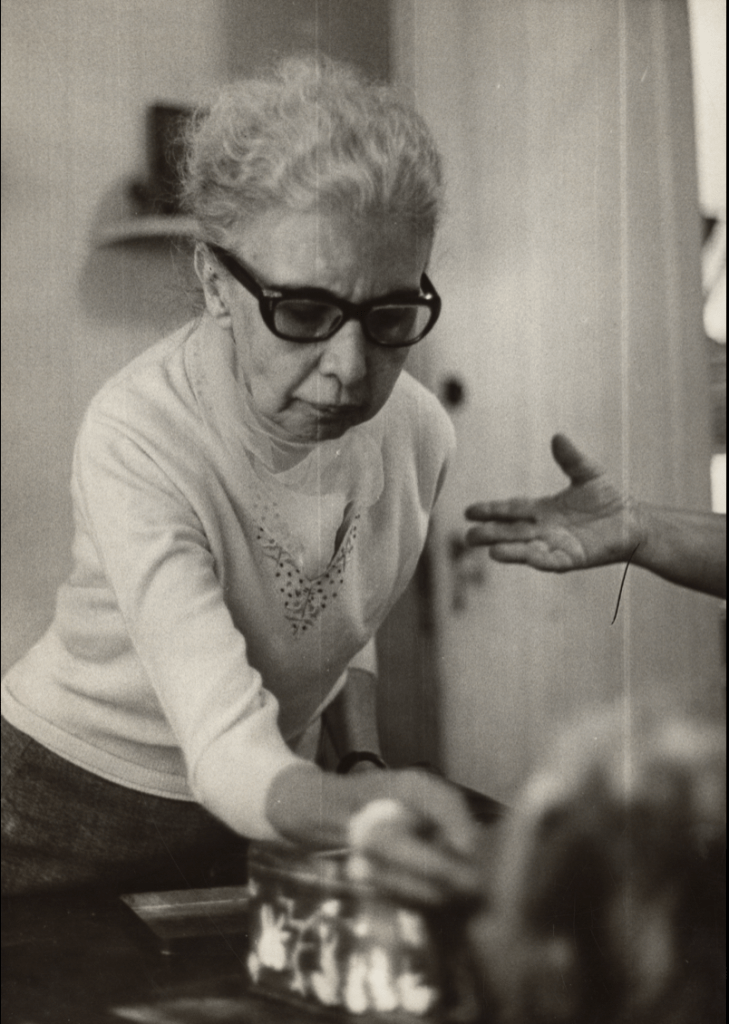

Image retrieved from WikiMedia Commons.

Marcela Costa

If creativity, rebellion and innovation are indispensable vehicles to bring about change, Brazilian psychiatrist and health humanities pioneer Nise da Silveira was a shining example of these qualities. Born in the impoverished Northeastern region of Brazil in 1905, she was the first woman to graduate from her medical school, among 157 men (Frayze-Pereira, 2003). She was incarcerated in the Brazilian Uprising of 1936 by the fascist dictatorship, alongside protesting artists, writers, and political personalities; and she went on to face political and personal resistance to her ideas from a stoic, unchanging protocol of mental health care for schizophrenic patients (Frayze-Pereira, 2003).

Nise da Silveira began her work as the director of occupational therapy at Pedro II Psychiatric Centre in Rio de Janeiro in 1946, encountering a vastly different model of care from the one she would leave behind upon her retirement in 1975 (Silveira, 1981). As Paulin and Turato (2004) describe, the psychiatric hospitals of mid-century Brazil were “mostly exclusionary in function, isolating the patient from the community, guarding them from the supposed danger they represented.” Ambulatory care was only present as a medication dispensary, and social determinants of mental health and illness were largely ignored (Borba, 2011). Non-pharmaceutical therapy was also chiefly available through psychosurgery (i.e. lobotomy) and insulin therapy – approaches that are all controversial (at best) in today’s medicine (Paulin and Turato, 2004).

On September 9th, 1946, Silveira founded the painting workshop at Pedro II along with three young artists. The workshop was supposed to be a regular part of the department of occupational therapy, but the diagnostic, therapeutic and artistic qualities of the artwork it produced turned it into something much larger. The instructors — artists with no mental health training — would bring patients into the workshop and allow them to create free and unprompted paintings, using materials that ranged from acrylic and oil paints, to crayons, to colored pencils, pens and markers (Silveira, 1981).

Silveira’s vocal critiques of the care model she encountered were consistent from the beginning of her directorship in the 1940s until the early 1980s, when Brazilian psychiatry underwent a nation-wide reform that shifted hospital-based models of care into individualized regimes and used extra-hospital resources as much as possible (Paulin and Turato, 2004). Most impactful among the psychiatric reforms were the steps taken towards the de-stigmatization and social rehabilitation of formerly institutionalized psychiatric patients (Bill 10.216/02).

Nise da Silveira had a strong influence upon Brazilian psychiatric reform. Her book, Images of The Unconscious, was published in 1981, and recounted her experiences instilling an arts-based model of therapy into Pedro II. In facing the difficulties of inhumane and outdated care, Silveira sought help outside of medicine, “in art, in myth, religion, [and] literature, where the most profound human emotions can always find forms of expression” (Silveira, 1981). In this article, I will discuss how art played a role in informing, illustrating and guiding Nise da Silveira’s psychiatry, inspiring the largest revolution ever undergone in Brazilian mental health care.

“Images of the Unconscious”: Art as Diagnosis

Nise da Silveira’s endeavor to unite the arts with clinical psychiatry came from the realization that a purely clinical language fares poorly in communicating the intricacies of psychological symptoms between patient and doctor, especially in her specialty, schizophrenia. As early as 1952, Brazilian psychiatrist Iracy Doyle corroborated Silveira’s conclusions, drawing attention to the need to comprehend the “emotional colorfulness, of which scientific terminology is devoid.” After early experiences in occupational therapy, Silveira soon realized that the easiest way to access the riches of the unconscious of schizophrenic patients was through free painting, drawing and sculpting (Silveira, 1981).

Silveira also used the arts to inform a critical look at the psychiatric examination techniques of the time. She understood the “orientation questions” — what’s your name? where are you? what day is it? — as superficial and of limited reach, writing, “A patient who correctly answers orientation questions may reveal in the painting workshop a completely subverted spatial experience.” Through symbolism, color and imagery, freely created paintings expressed an arsenal of inner turmoil. Silveira customarily referred to her patients’ artwork as the entryway to the unconscious (1981).

Moreover, the artwork, as Silveira later realized, had not only diagnostic but prognostic value. One of the most prolific artists at Pedro II, Emygdio de Barros, created a series of paintings in which geometric shapes, at first chaotic, followed a pattern of continuous organization over time. Silveira postulated that the organizing and sequencing of figures in Barros’ paintings reflected a progressive controlling of internal space and correctly predicted his approaching recovery and discharge. (Silveira, 1981)

“Heightening of Imaginary Creativity”: Art as Therapy

The therapeutic value of the arts at Pedro II was first apparent in the satisfaction expressed by the patients and, above all, their sorrow when they couldn’t pay their daily visits to the inks and canvases. A patient, Fernando Diniz, famously described the feeling as “an acid spilling on his life” when he spent 30 days away from the workshop because of an instructor’s leave of absence (Silveira, 1981).

Silveira also made clinical observations on the behavior of schizophrenic patients as they were painting. Her first observation was the abundance of paintings created by patients who had otherwise low activity and interaction levels (Silveira, 1981). Crucially, these patients had never painted before, but manifested what the psychiatrist described as an “intense heightening of imaginary creativity” (Silveira, 1981). She postulated that reason for such creative expression was the mentally demanding, active nature of painting. In the words of Fernando Diniz: “The images take over a person’s soul.” Painting would thus become a defense against the inundation of the pathological contents of the unconscious (Silveira, 1981).

It was not only the act of painting itself, but the contents of the paintings that were therapeutic: art by schizophrenic patients tends to favor abstract and geometric shapes over objects or human figures. These symbols start off as chaotic, but later move on to becoming more organized. Most commonly, patients painted circles, around which they would place symbols, some even creating intricate mandalas, in an attempt to garner control over their inner mental spaces. Silveira described this phenomenon as the attempt for “auto-cure” (Silveira, 1981).

“True works of art”: Art as Legacy

The first art exhibition at Pedro II took place only a year after the opening of the workshop. Prominent art critics noticed the aesthetic qualities of the paintings created by the patients: “These images are […] harmonious, seductive, dramatic, alive and beautiful, constituting, in and of themselves, true works of art,” wrote art critic Mario Pedrosa in 1947. The critical praise only helped highlight a contradiction in the world of art and psychiatry: while critics understood the artistic value and beauty of the works from Pedro II, most psychiatrists insisted on looking into these paintings only for their clinical importance (Silveira, 1981). Even now, a better look at the artistic capabilities of schizophrenic patients may motivate doctors and the world at large to reconsider stigmatized thinking about schizophrenia and to recognize the prowess and creativity that, if not triggered by the illness, persists even in so-called “illness states.” For instance, Mario Pedrosa commented that the patients enjoyed unusual artistic freedom in their paintings, defying the academic rules and conventions of traditional art in a type of aesthetic liberty he called “Virgin Art”(Silveira, 1981).

Perhaps because of its extraordinary creative freedom, the art created by the patients at Pedro II has become part of Brazil’s artistic heritage. In 1952, Silveira founded the Museum of Images of the Unconscious in Rio de Janeiro. The Museum now holds over 350 thousand works of art by psychiatric patients, making it the largest collection of its kind in the world. It also functions as a center for research on art and mental health, and it has been named as part of the official national artistic patrimony (Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente, 2016). Meanwhile, some of the patients who began painting at the workshop of Pedro II went on to become nationally renowned. As recently as 2012, Rio de Janeiro hosted a 3-month exhibit of one hundred paintings by patients Emygdio de Barros and Raphael Domingues (Estadão, 2012).

“A message of appeal”: Art as Change

“Biography en lieu of case,” says Luiz Carlos Mello (1981), Silveira’s close friend and collaborator, of her modus operandi, “and the psychiatrist, the co-author or reader.” Here, Mello captures Silveira’s desire to place a patient’s thoughts, personality, and expressions at the front and center of psychiatry.

Silveira considered the paintings created by her patients as proof that intelligence and sensitivity remain intact even after years of schizophrenia. This new realization heightened her urgency to change the inhumane treatments and conditions in psychiatric hospitals, and she described the exhibitions of the artwork as “messages of appeal” for this change to come sooner rather than later (Silveira, 1981). She attempted to enact this change by providing a critical perspective and commentary on the current structure of psychiatric care, starting with her adamant advocacy for a higher prestige of the arts, both in medicine and in society at large (Silveira, 1981).

Attending anew to the spatial and aesthetic dimensions of mental health care, Silveira observed the rigid, cool architecture of the hospital itself and listened to patients’ complaints about feeling locked within the hospital walls. “The hospital mirrors the prison,” she writes when critiquing psychiatrists’ disregard for spatial issues in mental health care. By contrast, she situated the artistic workshop in an spacious room, with large windows surrounded by trees, grass and hills. The room itself has been the theme of several paintings by Pedro II artists (Silveira, 1981).

Despite her criticisms of older practices of psychiatry, Silveira demonstrated an extraordinary faith in her profession, particularly when medical practice was coupled with the power of artistic interventions to produce a more sensitive approach to caring for schizophrenic patients. She writes in 1981: “Psychiatrists keep repeating that schizophrenia is a very severe disorder, nearly impossible to cure… But they forget the that conditions for an effective treatment are also nearly impossible to assemble within a psychiatric hospital.”

Brazilian author Graciliano Ramos wrote of Silveira, whom he met when they were both in prison for political protest: for her, it was “not enough to be woman and Northeastern, doctor and psychiatrist; but [also an] early antipsychiatrist and communist in the fascist State” (Frayze-Pereira, 2003). There is no question that her example of innovation and rebellion through patient artistic expression guided a medical revolution; her contribution remains a model for the improvement, humanization and interdisciplinarity of health care in the future. Nise da Silveira passed away at the age of 94 in Rio de Janeiro and has been the subject of countless articles, books and a feature film, Nise – The Heart of Madness (dir. Roberto Melo, 2015). The Pedro II Psychiatric Hospital is now named The Nise da Silveira Municipal Institute (Estadão, 2012).

Marcela Costa is a fifth-year medical student at the Federal University of Pernambuco, in Brazil. She was an exchange student at the University of Toronto Scarborough, where she was introduced to the Health Humanities. Her research interests include women’s sexual and reproductive health, mental health and medical education.

References:

- Frayze-Pereira, João A. “Nise da Silveira: Imagens do inconsciente entre psicologia, arte e política.” Estudos Avançados, 17, issue 49, pp. 197-208, 2003.

- Silveira, Nise da. Imagens do Inconsciente. Vozes, 1981.

- Paulin, Luiz Eduardo and Turato, Egberto Ribeiro. “The prelude to psychiatric reform in Brazil: the contradictions of the 1970s.” História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos, 11, issue 2, pp. 241-258, 2004.

- Borba, Taiane. “O dispositivo ambulatorial de saúde mental no contexto da reforma psiquiátrica.” Portal Educação https://www.portaleducacao.com.br/conteudo/artigos/cotidiano/o-dispositivo-ambulatorial-de-saude-mental-no-contexto-da-reforma-psiquiatrica/67488 Accessed January 2018.

- Bill 10.216/02 Brazilian Constitution. 2003. Print.

- Doyle, Iracy. Introdução à Medicina Psicológica. Casa do Estudante do Brasil, 1952.

- Pedrosa, Mario. “Art Criticism.” Correio da Manhã, February 2nd 1947.

- Pedrosa, Mario. “Art Criticism.” Correio da Manhã, March 19th 1950.

- Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente. Sociedade Amigos do Museu de Imagens do Inconsciente. http://www.museuimagensdoinconsciente.org.br/#index Accessed in January 2018.

- Filho, Antônio Gonçalves. “Emygdio de Barros e Raphael Domingues ganham exposição no IMS.” Estadão, http://cultura.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,emygdio-de-barros-e-raphael-domingues-ganham-exposicao-no-ims-imp-,905787 Accessed January 2018.