Daisy Butcher // Content warning: Sexual violence and female genital mutilation

In both Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) and Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘Carmilla’ (1872), men from medical backgrounds slay wayward, sexual vampiresses. The nineteenth century saw the general encroaching of male doctors over female patients: while midwives had traditionally held authority in managing women’s health and childbirth, these domains were now firmly in the control of the new field of gynaecology, managed by a male-dominated medical establishment. The texts I examine in this piece theorize the female vampire as a reflection of this encroachment. I argue that the female vampire symbolizes historical anxieties surrounding female bodies, specifically “diseases” such as hysteria, chronic masturbation, and nymphomania. The causes for these “diseases” in women led back to the clitoris: as Robert Mighall has argued, nineteenth-century novelists used vampires to symbolize the demonized portrayal of onanism during this period (cited in Mulvey-Roberts 99). In the medical literature of the time, the clitoris was either a source of evil and depravity, or omitted altogether. It was both ever-present and never-present, a monster hiding under the marital bed that preyed on innocent women who needed to be liberated from its lascivious clutches.

This pathologized view of the clitoris is a uniquely nineteenth-century phenomenon in Western thought, as thinkers of previous centuries believed that male and female orgasms worked together during intercourse to create life. The female clitoral orgasm, believed to be reproductively necessary, was therefore encouraged and celebrated. Kirsten Bell reveals how it was not until Theodor Bischoff’s 1843 discovery that “ovulation in dogs occurs independent of sexual intercourse” that specialists conceded that “the female orgasm serves no reproductive purpose and was therefore unnecessary to the perpetuation of life” (133). The clitoris was rendered a superfluous anatomical appendage. This new belief that the clitoris served, at best, no purpose in the production of life, and, at worst, brought on diseases both physical and moral, led to the rise of clitoridectomy—or as we now call it, female genital mutilation.

The pioneer of the clitoridectomy was Dr. Isaac Baker Brown (1811-1873), who advocated the procedure as a near cure-all for women’s “nervous disorders.” Brown’s case notes help to establish the symbolic link between cliterodectomy and vampirism: one patient, an Irish hysteric, attacked the surgeon, tried to bite the matron, lost and then regained consciousness, and finally declared her thirst for blood, especially child’s blood (Mulvey-Roberts 101). The horror of such stories notwithstanding, physicians like Baker Brown saw themselves as heroes vanquishing evil, and they relied on a romance tradition in their brutal attempts to rescue what they saw as fallen womanhood. As the critic Jill Raitt asks, “How many of our own fairy tales and chivalrous legends portray an eager hero who must go through many perils and eventually kill the dragon (pull the teeth) in order to win the fair young maid and her treasure (the brimming bowl)?” (Raitt 426). In this tradition, the feminine is both the monster and the prize.

This association between the feminine and the monstrous is made explicit with Laura and Carmilla in Le Fanu’s tale, and Lucy and Mina in Dracula. A first, and literal, instance of this attempt to “pull the teeth” occurs in “Carmilla,” when a peddler arrives at Laura’s schloss to sell protective talismans to both the girls. Noticing the vampire Carmilla’s unusually sharp tooth, the peddler suggests filing it down for her—in effect, attempting to pull the teeth of the vagina dentata, or to excise the corrupting clitoris from the female.

Addressing Laura, the peddler comments, “[y]our noble friend, the young lady at your right, has the sharpest tooth—long, thin, pointed, like an awl, like a needle; ha, ha!… here are my file, my punch, my nippers; I will make it round and blunt, if her ladyship pleases; no longer the tooth of a fish” (Le Fanu 269). Naturally, Carmilla is offended and indignant towards him and his quackery. The role of the peddler seeking to extract her unsightly and dangerous tooth emblematizes the patriarchal aim of sexual surgery. This reading is further reinforced by Jill Raitt’s use of the pulling of teeth as a metaphor for clitoridectomy: “From the primal fear expressed in the vagina dentata stories has come the cruel treatment of women by which their teeth were pulled (clitoridectomy, both actual and psychological). After such an operation, women become tractable, tamed, obedient daughters and faithful wives” (Raitt 423). Using Raitt’s symbolic reading, we can see that the peddler attempts not only to force Carmilla to conform to conventional beauty ideals, but also to domesticate, disempower, and, effectually, castrate her.

The peddler’s attempt to file down Carmilla’s teeth is the first instance of symbolic clitoridectomy. The second instance is the staking and decapitation of the vampire Carmilla in her coffin, a ritual act performed by Baron Vordenberg:

The two medical men, one officially present […] the leaden coffin floated with blood, in which, to a depth of seven inches, the body lay immersed. Here, then, were all the admitted signs and proofs of vampirism. The body, therefore, in accordance with the ancient practice, was raised, and a sharp stake driven through the heart of the vampire, who uttered a piercing shriek at that moment, in all respects such as might escape from a living person in the last agony. Then the head was struck off, and a torrent of blood flowed from the severed neck. (Le Fanu 315-316)

This death scene is violent and rapacious; importantly, it is superintended by “two medical men,” suggesting the complicity of the Victorian medical establishment in the brutal treatment of women.

Dracula revises and elaborates the imagery of staking and beheading in “Carmilla.” While Le Fanu’s novel was written contemporaneously with the peak of clitoridectomy, Stoker’s later book is steeped in the procedure’s legacy in medical thought. Dracula manifests the interconnectedness of the clitoridectomy, the pathologization of the feminine, and the figure of the vampire. Bram Stoker came from a medical family and was familiar with contemporary advances in medicine, and his work blurs the boundaries between the supernatural and medicine. In addition, three of Stoker’s four brothers were doctors. The eldest, Sir William Thornley Stoker, was a celebrated surgeon specializing in gynaecology, and he made history by performing the first successful hysterectomy in Ireland (Mulvey-Roberts 96). Thornley, who lived with Bram, had a profound influence on the writing of Dracula. In her analysis of the surgical tropes of Dracula, Marie Mulvey-Roberts explains how “Thornley kept an eye on the accuracy of surgical instruments in Dracula and, shortly before the novel went to press, corrected his brother’s references to operating knives by changing them to post mortem knives” (Mulvey-Roberts 97). Thornley’s surgical influence extended to the gynaecological theory of Dracula. The elder Stoker brother was an advocate of female sexual surgery, and even performed a clitoridectomy himself in June 1885 (Mulvey-Roberts 96). Mulvey-Roberts documents that “Thornley excised the clitoris of a lunatic woman, after she confessed to being a masturbator. This was nearly two decades after clitoridectomy had been discredited as an operation in Britain following Brown’s downfall, though it was still being carried out in lunatic asylums” (Mulvey-Roberts 118).

With this evidence of Thornley Stoker and his influence on the writing of Dracula, one can view the sexually charged nature of Lucy’s staking as unrivaled by any other death in the novel and saturated with sadism and medical terminology and themes. It encapsulates sexual violence, orgasm, and subjugation of the wayward woman in a symbolic clitoridectomy. Stoker’s description relishes in eroticism:

he struck with all his might. The Thing in the coffin writhed; and a hideous, blood-curdling screech came from the opened red lips. The body shook and quivered and twisted in wild contortions; the sharp white teeth champed together till the lips were cut, and the mouth was smeared with a crimson foam. But Arthur never faltered. He looked like a figure of Thor as his untrembling arm rose and fell, driving deeper and deeper the mercy-bearing stake, whilst the blood from the pierced heart welled and spurted up around it…. And then the writhing and quivering of the body became less, and the teeth seemed to champ, and the face to quiver. Finally it lay still. The terrible task was over… (Stoker 201-202).

The symbolic staking and removal of the head later in the text corresponds to Victorian clitoridectomy intended to produce the ultimate passive female, the pretty corpse. In psychoanalysis, decapitation is similar to losing teeth in its castration symbolism, which strengthens the ties to clitoridectomy imagery surrounding Lucy’s slaying. Dehumanized to the status of “Thing,” Lucy is further rendered the passive recipient of male force as Arthur strikes her repeatedly with the stake, maiming her with symbolic rape in order to desexualize her. (The killing is carried out on what would have been Lucy and Arthur’s wedding night—a significant time, since clitoridectomy was often done to improve marital relations by “correcting” unruly wives.) In Lucy’s final moments she reverts back to her former self, with soft, innocent features and “her face of unequalled sweetness and purity” (Stoker 202). As Mulvey-Roberts summarizes, “Lucy undergoes an angelic transformation through the destruction of her body” (109). The same transformation is documented by Victorian sexual surgeons, who advocated and defended their surgeries as saving marriages and protecting women from themselves.

Lucy’s bloody mouth points to another conflation of vampirism with disease: as he was preparing the manuscript of Dracula in 1896, Stoker read in the New York World that “symptoms of consumption were sometimes mistaken for vampirism.” In the nineteenth century, a diagnosis of tuberculosis (phthisis), which caused the sufferer to spit blood, was freighted with moral weight, since the disease was supposed to arise from onanism. In this historical context, Lucy Westenra’s bloody mouth signifies her heightened sexuality through a matrix of pathological associations (Mulvey-Roberts 95).

Finally, the vampire slayer and the clitoridectomy surgeon shared tools of the trade, carrying similar instruments and practicing similarly brutal methods. Observing Dr. Isaac Baker Brown, a medical student commented on his “hooked forceps” and “cautery iron,” which he used to “effectually destroy” the genitals (Scull and Favreau 251-252). Just as Arthur strikes the stake with over-enthusiastic fervor, the medical student describes Brown as excessively and obsessively destroying the female genitals. In Dracula, Van Helsing uses the same set of tools in preparation to meet the vampire: he “Took out a soldering iron and some plumbing solder, and then a small oil-lamp, which gave out, when lit in a corner of the tomb, gas which burned at fierce heat with a blue flame; then his operating knives, which he placed to hand.” As Mulvey-Roberts notes, these tools were also used for clitoridectomies. But it is striking how useless the operating knives and soldering iron prove to be in Van Helsing’s meeting with the vampire—in fact, they are there for symbolic purposes only.

Ultimately, the clitoridectomy fell into ignominy as a medical procedure, and Isaac Baker Brown was disgraced in 1866 for performing clitoridectomies without consent of his patients (Mulvey-Roberts 107). But the legacy of his practice survives in Dracula with Van Helsing’s masterminding of the nonconsensual operations on Lucy Westenra; Dr. Seward initially objects to “mutilating the body of the woman whom I had loved” when he hears the plan for the rapacious staking of Lucy (Van Helsing himself refers to the staking as an “operation”) (Stoker 154). By driving the stake through Lucy, Arthur will “strike the blow that sets her free”—but this “setting free” is a euphemism for destroying a woman who has deviated from the desirable norm (Stoker 200). Thus, even as they challenge the strictures of conduct for nineteenth-century women, the vampiresses of Victorian fiction are products of the medical male gaze. Lucy and Carmilla offer hyperbolic personifications of the threat of female sexuality, and, these novels show, the medical establishment used such personifications to justify a torturous surgery as a putative “cure.”

Works Cited

Bell, Kirsten. “Genital Cutting and Western Discourses on Sexuality,” Medical Antholopology Quarterly, Vol.19, Issue 2, 2005.

Le Fanu, Sheridan. In a Glass Darkly, “Carmilla,” Oxford University Press, 1993.

Mulvey-Roberts, Marie. Dangerous Bodies: Historicising the Corporeal, Manchester University Press, 2016.

Raitt, Jill. “The ‘Vagina Dentata’ and the ‘Immaculatus Uterus Divini Fontis,'” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 48, No.3 (1980), 415-431.

Scull A., and D. Favreau. “The Clitoridectomy Craze”, Social Research, Summer, Vol.53, Issue 2, 1986, 251-252.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula, Oxford University Press, 2011.

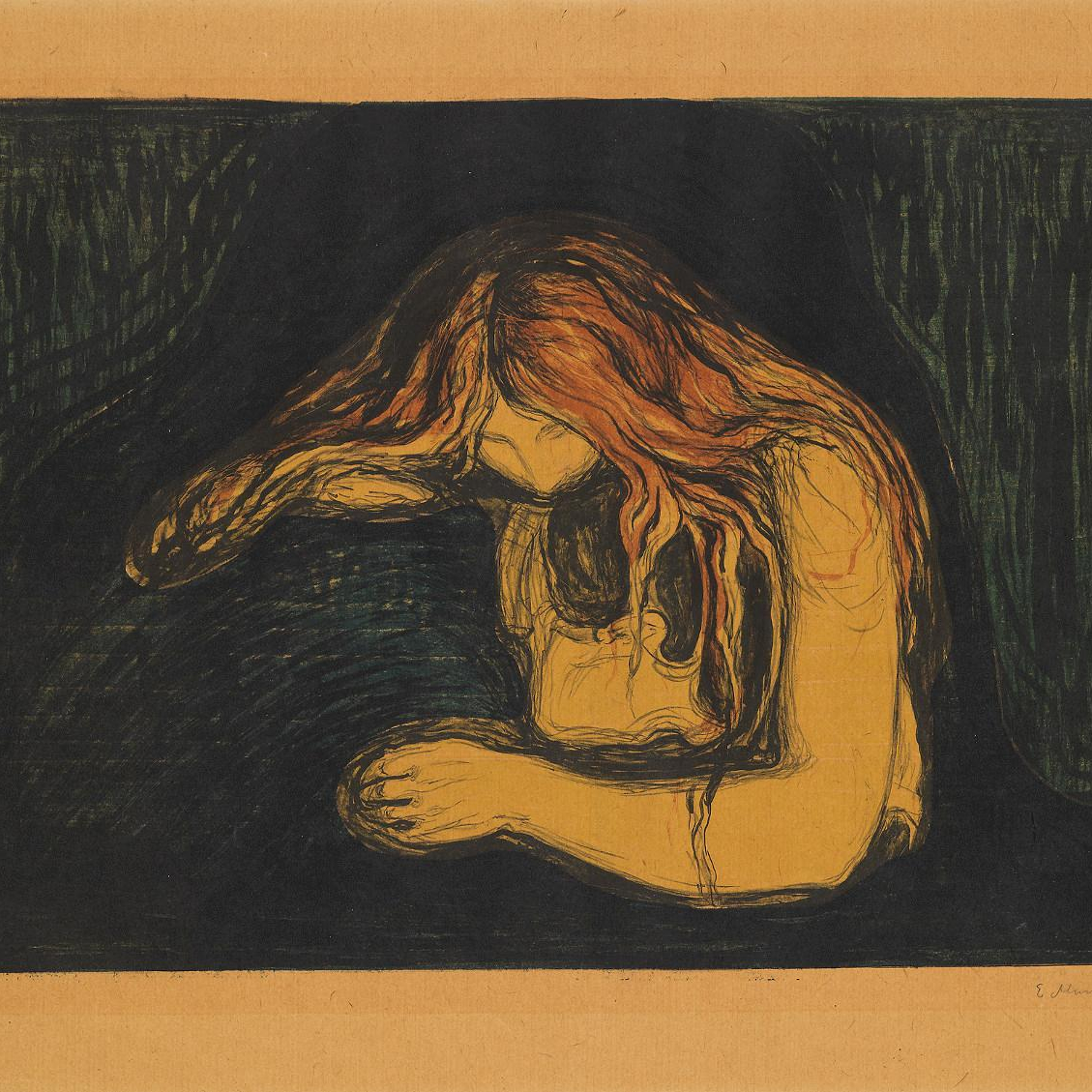

Image source: Edvard Munch, Vampire II (1902), from the Nasjonalmuseet collection.

Daisy Butcher is a doctoral student at the University of Hertfordshire, where she has just begun a thesis attached to the Open Graves, Open Minds project on vagina dentata in popular monsters with chapters on vampires, mummies and killer plants . She has presented papers at multiple conferences across Europe and the UK, most recently

at the Universities of Hertfordshire, Bishop Grosseteste, Aston, Manchester, Oxford and she also attended ‘Athanatos’ The World Mummy Congress, Santa Cruz, Tenerife in May 2018. She was awarded best student paper at the “Reimagining the Gothic” Gothic Networking Day in 2016 and won 2nd Place at the University of Hertfordshire’s Vision and Voice Research Award 2018.