Sneha Mantri // Between the late seventeenth century and the early nineteenth century, Europe canonized a new scientific order, based on experimentation and logic rather than the empiricism and introspection that characterized traditional analytical thought since Aristotle. This dramatic paradigm shift, now well established as the scientific method, led to astonishing leaps of knowledge. For medicine, in particular, new theories rapidly replaced the Hippocratic/Galenic tradition. Specifically, the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw the development of the nervous disorder, both as a description of physical symptoms and as a way of wresting power back from the increasingly mechanistic worldview of early modern medicine. In the first part of this three-part essay, I take a look at the social and medical structures that led to the rise of invalidism. Part 2 will examine the flourishing—and criticism—of the cult of the invalid against the backdrop of the Industrial Revolution and the World Wars; Part 3 will bring invalidism into the present era of computer-aided diagnosis and ICD-10 codes.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, traditional medicine adhered to the principles of Hippocrates and Galen, a Greek physician and Roman surgeon, respectively, who had between them set down the basic rules for the practice of medicine. For example, ancient medicine and its early modern descendant relied on the analogy of illness as an imbalance in humors. Four bodily fluids (black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm) controlled the patient’s health; the physician devoted his energy to restoring the proper balance between the four fluids via purgation and blood-letting. Illness, for the pre-moderns, also had a spiritual or psychological component. The traditional association of the four humors with the four temperaments (melancholic, choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic) directly linked illness and personality. Because health was associated with rational balance of these elements, and illness with irrational imbalance, physicians and patients did not look for external causes of disease, such as germs and toxins[1]. Instead, the patient was presumed to be completely responsible for his own lack of health, either through angering the gods or because he failed to follow certain rules for maintaining his own humoral balance.

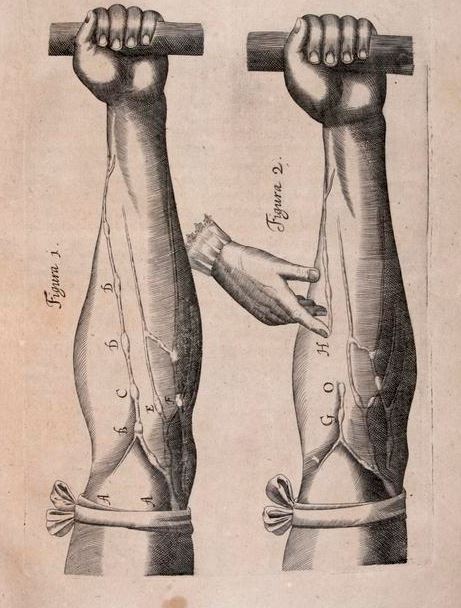

With the Enlightenment, however, increased scientific and mechanistic scrutiny on disease processes began to reveal fractures in those traditional metaphors of illness. In 1628, Sir William Harvey published De Motus Cordius, which explained the circulation of the blood in mechanical rather than humoral terms. Harvey’s proposal that venous and arterial blood both stemmed from the heart and flowed into two separate but connected loops of vessels was backed by thousands of vivisection experiments and clashed with the accepted Galenic model, which theorized that blood diffused throughout the body. This landmark paper directly confronted ancient medicine with experimental proof. Similar challenges soon followed, including Thomas Willis’ 1664 Cerebri anatome which described for the first time key structures in the brain and spinal cord, including the crucial circle of arteries at the base of the brain that bears his name. By the latter half of the seventeenth century, Galenic medicine had fallen out of favor, replaced by iatrochemistry, the idea that the body is subject to the same physical, mechanical, and chemical laws governing inanimate objects.

In spite of—or perhaps because of—this increasingly rational approach to disease states, nervous illnesses burst onto the scene. In the early eighteenth century, an alarming epidemic of “nerves” among upper-class Englishwomen, estimated as high as two in three, led George Cheyne to call invalidism “the English Malady.” Cheyne associates nervous illness with the “Wealthy and Voluptuous,” forever linking invalidism with its sociocultural milieu: the poor, the enslaved, the disenfranchised, did not have the luxury of nervous illness. Invalidism took many forms, but the core belief was that the subject’s nerves were too refined, too subtle, to bear the weight of ordinary existence. Even as experimentalists like Luigi Galvani[2] and Jean-Pierre Flourens[3] championed new ways of knowing, invalids drew on established cultural ideas of sensibility and sentimentality. In some ways, the cult of invalidism was a subversion of the earlier cult of sensibility, which was developed in the eighteenth century both to indicate refinement of character and also to reinforce cultural boundaries about the roles of women. Moreover, because nervous illness could not be cured by administration of a traditional purgative or elixir, physicians could do little more than advise rest and relaxation. “Nerves,” therefore, were a culturally acceptable means by which physically healthy but socially constrained people, usually women, might gain all the social benefits of illness with very few of the physical inconveniences.

The early modern invalid, however, did not emerge from oppression into total freedom. He or she might be subjected to dangerous medicines as physicians tried their best to effect a cure. Socially, the invalid had little time to himself or herself, having to endure inquisitive neighbors’ “sick visits” which grew in popularity during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Satirists like Jane Austen attacked invalids as manipulative (e.g. Mrs Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, Mr Woodhouse in Emma); James Gillray and other cartoonists portrayed them as merely grotesque. The truly insane, who in pre-modern times were believed to be touched with divinity, were now institutionalized in newly created asylums,[4] because they posed a threat to the order and rationality of the Enlightenment. Sufferers from nervous illness, therefore, had to tread a very fine tightrope between the agency that invalidism provided and the physical and social dangers it posed.

Invalidism also made a profound statement about the role of medical science in lay culture. As the eighteenth century turned into the nineteenth, the skepticism with which William Harvey and his intellectual descendants examined Hippocrates and Galen was applied to early modern medicine itself. In a world that was rapidly changing, many expressed their uncertainty and apprehension not through words but through their bodies. In the next segment of this three-part essay, I will examine the ways in which the invalidism responded to the social upheaval of the Industrial Revolution and the World Wars.

Featured Image: Self-propelled wheelchair of paralyzed watchmaker Stephan Farffler from 1655 built by him at the age of 22, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] The germ theory of disease was developed after Louis Pasteur definitively disproved the theory of spontaneous generation (the idea that microorganisms are created by air and inanimate matter) in the 1860s. Even so, germ theory was not accepted widely until the turn of the 20th century, and basic principles like handwashing remain a major challenge for hospitals seeking credentialing by the Joint Commission.

[2] Galvani’s 1791 treatise, in which a dead frog is made to jump after application of electrical stimulation, later inspired Mary Shelley’s examination of the moral and ethical implications of re-animation in Frankenstein.

[3] Flourens’ 1815 demonstration that cortical ablation produces predictable deficits in behavior, movement, or sensation paved the way for modern neurologists to localize the lesion and proved Thomas Willis’ declaration that the brain is the “seat of the soul.”

[4] The asylum at London’s Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam) was the most famous of a series of quasi-public demonstrations of the theatre of the insane. Public visiting was a popular holiday activity from the 1680s until the financially-motived introduction of a paid ticket system in 1770; visitation was finally curtailed with the passage of the Lunacy Act in 1845.