Sarah L. Berry // Keep your politics out of my uterus. I can’t breathe. My Body, My Choice. Current social justice movements proclaim that not all bodies are free in the twenty-first-century United States. Demonstrators use public spaces to stage die-ins, march on Washington, D.C. and state capitols, and gather support over social media. Founded by women, movements like Black Lives Matter and reproductive justice underscore ties among politics, racism, misogyny, and health, and they protest the vulnerability of the bodies of women as well as children and adults of color to many forms of institutional violence. While these movements seem ultra-modern because of their social media launchpad, their roots are in nineteenth-century waves of reform leading up to the Civil War. This 4-part series will examine the vital role of health reform in social justice movements at pivotal moments in U.S. history from abolition to the Affordable Care Act.

The first social justice movements linked health, individual liberty, and spiritual well-being.[1] In 1776, the Declaration of Independence denounced the debauched, “tyrant” King George III at the same time as “The Destroyer Displayed,” an anti-alcohol pamphlet by Quaker Anthony Benezet, launched the temperance movement. In the new republic, health was inextricably linked with liberty for all. Reform was spurred by churches—the earliest common peoples’ networks—and Evangelical emphasis on public speech and conversion. Quaker churches were closed to the public, but the emphasis on doing no harm to others fostered the abolition movement. In general, the church gave women as well as people of color opportunities to speak publicly and to participate in social affairs through religious work.

At the same time, in the wake of the Revolutionary War, professional medicine expanded, pushing out traditional midwives and home healthcare provided by women. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who became something like a one-man Surgeon General/CDC office for the new nation, endorsed “heroic” treatment methods like mercury purges and bleeding with lancets or leeches, remedies that often made patients worse.

To health reformers in the 1830s, liberty meant freedom from diseases caused by intemperate living—a lack of self-government, fittingly enough—and from physicians’ expensive and painful treatments. Gurus from Sylvester Graham (of cracker fame) to Amelia Bloomer (of ladies’ pants fame[2]) preached liberty and the pursuit of happiness through a regimen of healthy diet, dress, sexual hygiene, and exercise. Others started their own patent medicine systems; Samuel Thompson’s was based on botanical medicines such as lobelia and cayenne pepper, which were milder, safer versions of heroic therapies that could be administered without doctors. Thompsonianism cultivated a network of subscribers to purchase the product (a home medicine chest) and trainers taught patients to diagnose and medicate themselves.

While Evangelicalism took on health reform, it also provided the platform for underground antislavery activists to form a public movement. Antislavery agents, particularly Quakers, had established secret networks running from south to north to assist freedom seekers since the 18th century.[3] But the public anti-slavery movement gained steam with the founding of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, when health reform was underway.

As wave after wave of reform swept the new nation, they all had something in common: they allowed women to attend meetings and often participate. The kind of women who attended Graham’s lectures or anti-slavery meetings saw social injustice such as slavery as a public health threat. One abolitionist network in upstate New York demonstrates these connections well.

Rochester residents Amy and Isaac Post were Quakers who ran a stop on the Underground Railroad and labored for half a dozen movements; their zeal, connections, and hospitality led Frederick Douglass to the city to publish The North Star. Their local Western New York Anti-Slavery Society was the first in the nation to include women and people of color.[4] Post befriended Harriet Jacobs, a freedom seeker who had spent seven years in a crawl space before making it to the north. Jacobs had come from a North Carolina community in which several generations of women—free, enslaved, and slave-owning—worked together to support Jacobs in fleeing sexual abuse from her enslaver by hiding her, doctoring her with homemade and alternative medicines, and helping her protect her children.

At this time in Rochester, Amy Post, also a mother, shared a lively exchange of healthcare information with her many female relatives and friends.[5] Wary of physicians, they coached each other in difficult births and exchanged recipes that favored common field plants and other effective ingredients at hand. In these mirrored women’s worlds, a collaboration for reproductive justice emerged when Jacobs met Post. Post encouraged her to write her life story for the cause of abolition. Jacobs wrote one of the only full testimonies by a woman of slavery’s sexual and psychological harms for girls, women, and mothers. Moreover, she created an intersectional narrative revealing the compounded effects of race and gender on bodily and mental health. Her enslaver, a physician, links individual with institutional violence and Jacobs calls free Northern women to remedy this “blight” of slavery. The confessional space between women in which Jacobs could “whisper her cruel wrongs into the ear of a very dear friend”[6] shored up women’s cross-racial alliance as agents of change.

The first U.S. social justice movements linked the individual’s pursuit of happiness and health to a moral, equitable social structure. Abolition took its mission and campaign tactics from temperance and health reform, and its leading female activists next launched the women’s rights movement. Part 2 will explore the ways in which women organized social reform from the margins and the center of medicine in the 1850s.

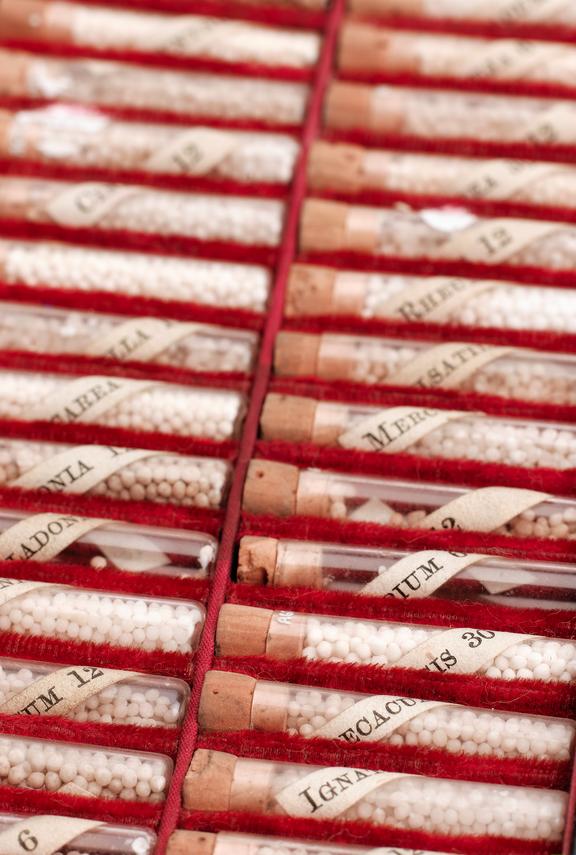

Featured Image: Small black leather covered medicine chest, lined with red velvet, containing small scoop and 30 labelled glass phials of homoeopathic medicines, prepared by W. Headland, chest inscribed Dr. Malan’s Family Medicine Chest, English, 1870-1930. Close up detail, oblique view. Science Museum, London. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

[1] There’s an established literature that situates social justice movements in terms of political and civil rights scholarship. The essays in this series reframe this history by bringing medical and health history to the foreground.

[2] Bloomers were first created by Elizabeth Smith Miller in 1851 and almost immediately popularized by Amelia Bloomer, the first woman to edit her own newspaper, The Lily (a temperance organ). See Hewitt, Radical Friend, p. 183.

[3] Larson, Kate Clifford. Bound for the Promised Land: Harriet Tubman, Portrait of an American Hero. Ballantine, 2004.

[4] Hewitt, Nancy A. Radical Friend: Amy Kirby Post and Her Activist Worlds. UNC Press, 2018.

[5] See the Post Family Papers Project, a cache of manuscript letters digitized by the University of Rochester (NY).

[6] Harriet Jacobs to Amy Post, June 21, 1857. In Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Edited by Jean Fagan Yellin. Harvard UP, 1987, p. 242.