James Belarde //

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Both this article and Part 1 discuss a short play written by the author that can be found in its entirety here.

“I don’t trust anyone who doesn’t laugh.” -Maya Angelou

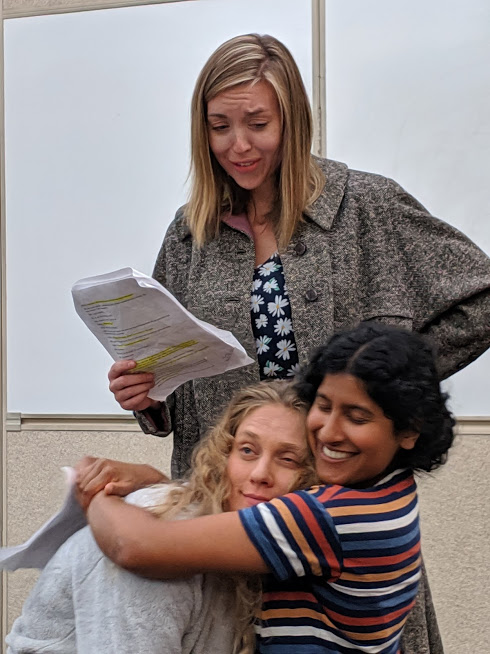

In my last article, I discussed a comedic (and tragic) play I wrote that was produced by my fellow students on Columbia University’s medical campus last summer. Using this, I examined how artistic collaboration allows each member of the creative team to escape the limits of their individual perspectives and express experiences with audiences more fully than they might be able to alone. In this way, an absurdist play based on my feelings of powerlessness in medical school became a performance expressing the conflicted emotions surrounding nostalgia, memory, dementia, nursing home care, loss of identity, and loneliness as my classmates plunged deeper into the text.

But while this example illustrates an important obstacle in rendering one’s personal pain as art, it doesn’t entirely answer the question a patient once asked me disappointedly: “Why don’t my doctors laugh with me?” In her case, trying to share her experiences and pain through jokes, it wasn’t the “performer” that was hesitant to open her perspective to an audience. Rather, it was her audience, the healthcare team, that was struggling to explore this perspective with her.

Of course, appreciating the humor of a sufferer can be a difficult process for anyone, from family and friends to professional caretakers. But why is this so? Does it stem from a concern that the humor is a denial mechanism, one that shouldn’t be encouraged? Are there worries about appearing insensitive by laughing at jokes founded in pain? Or does this struggle suggest a more fundamental difficulty in empathizing with a suffering body? To explore these questions, I again turned to the spirit of collaboration and interviewed the director and cast of my play about how their own experiences with health and medicine informed their performances last summer.

One of the recurring themes in the conversation that immediately struck me was that just as comedy is a subjective art form sensitive to shared experience, the perception of illness can vary depending on one’s relation to it. Phyllis Thangaraj (an MD/PhD student who played the energetic child) suggests this not only depends on whether one is the person suffering, but also one’s specific relationship to the sufferer. This idea came from her memory of being chastised as a child by her grandfather for occasionally finding the forgetfulness of her grandmother with dementia humorous. Both she and her grandfather were loving family members. But as a child, Phyllis was a more passive observer and could laugh at times, while her grandfather was more closely invested in a caretaker role and found this rude.

While one could argue the above example is simply a product of children being less sensitive toward illness, another personal story from the director, Eduardo Perez-Torres (an MD/PhD student), provides evidence that there is a deeper conflict at play when finding humor in the context of illness. Drawing on significant personal experience with Alzheimer’s and dementia in his family, Eduardo remembers a time when his grandmother wouldn’t recognize him. Instead, she would readily chat and joke with him about whatever was on her mind, happy that a young man was willing to pleasantly engage with her. Sometimes Eduardo’s parents tried to get his grandmother to remember him, disappointed with her forgetfulness. But Eduardo wondered if it might not be better to let her enjoy this interaction as it was rather than distress her with something she couldn’t remember. Again, here is a clear divide between discomfort with an illness and a willingness to exist with it, sometimes lightheartedly.

This conflict is seen in many other medical problems as well. Kelsea Breder (a nursing PhD student who played the lonely, forgetful Godot) raised the point that for many patients, the symptoms they would prefer to have treated often differ from what their caretakers see as important. Using the example of autism spectrum disorders, she explained that while many medications have been developed to reduce repetitive behaviors seen in these disorders (such as hand-flapping or rocking), many patients would prefer research to focus on treatments that improve their communication deficits. In fact, these patients frequently regard the repetitive behaviors as calming when they feel overloaded. But because these unusual visible symptoms often make non-autistic observers uncomfortable, there is an assumption that these are the priority for treatment. In approaching illness this way, who are we trying to comfort? The patient or the caretakers and observers who are using their own judgment rather than the sufferer’s lived experience? And which should be the goal of medicine?

This brings us back to the subjectivity of illness and humor. Is a similar conflict responsible for the disconnect that led my patient to ask why her doctors wouldn’t laugh with her? Perhaps some caretakers can’t find a patient’s attempts to poke fun of their illness funny because they can only imagine the distress they would feel if they were suffering similarly. It would thus be easier to assume the humor stems from denial than acknowledge that, from the perspective of the patient’s lived experience, there is still room for laughter despite the pain.

Clara Wellons, a student in the Mailman School of Public Health who played the goat, offered some observations on her performance that show how much more audiences laugh when this experiential gap between the sick and the healthy is narrowed. Interpreting the goat character as a nursing home patient with late-stage dementia, Clara notes that her biggest laughs came when her character showed moments of increased self-awareness, something dementia patients do experience. It was almost as though, through the mysterious veil of illness, the “goat” was winking at the audience and saying, “It’s okay to laugh. I’m still here. There’s humor even here.” But the audience needed an assurance it wasn’t all unimaginable pain. This was still a relatable human being with a full range of emotions, including humor.

Perhaps this is the psychological leap healthy observers in life and the comedy arts must make to genuinely enjoy humor from illness. One must empathize with the sufferer in such a way that they acknowledge not only the pain, but also the continued capacity for feelings beyond that pain. Aili Klein, an MD/PhD student who played the unseen but ever-present narrator, stressed this idea when discussing how comedic creations founded in pain can be effective without being insensitive. For her, it requires two closely related approaches: an awareness of how much suffering goes into comedy, and a willingness to treat that suffering with more respect. And this respect includes appreciating that a body in pain is still a complex, complete human. “After all,” she summed up, “I feel that comedy and tragedy are really just two sides of the same coin.”