At left: an image of a lottery machine, half-filled with numbered balls. Housebound citizens watch anxiously on televisions, waiting for their birth date to be called, disappointment mounting as it becomes clear their vaccination will now be happening fairly late in the process. The lottery itself is overseen by a military official in the precincts of the CDC, seemingly conferring upon the operation an air of order and efficiency. After a moment of spinning action generating suspense amongst the viewing audiences both within and outside the film, the ball drops from the basket, its number causing jubilation for a few, and dashing the hopes of millions more.

The scene described above appears towards the end of Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion (2011), a film that has become increasingly relevant since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and informs popular opinion of how a vaccine rollout in these circumstances should work. The film’s resolution both assumes an unquestionable pro-vaccination stance and presupposes that pandemics foster compliance in the general population. The lottery at the end of the film stands in for neoliberalism and its illusions of equity. Its mechanical impartiality affords an impression of fairness, calculated to mollify a desperate public and allay the doubts of cynics looking for signs of cronyism and preferential treatment. Beneath this façade lurks the crushing reality of a lifetime of neglect, lack of access, and denial of resources that someone from a racialized background in North America is far more likely to have experienced.

This is not to say that a COVID-19 vaccine rationing by lottery will necessarily take place in North America. However, as a metaphor for the myth of distributive justice and the way public health response often papers over structural inequalities, the lottery is worth considering more closely. As medical ethicist Harald Schmidt notes in an important article recently published in The Hastings Center Report, a vaccine lottery presupposes that each of us enjoys the same health benefits and is beginning from a position of equality. When one looks at the ways our health system (in both Canada and the United States) systemically disadvantages BIPOC, it becomes clear that citizens are beginning from very distinct places of inequality. A lottery that ignores this reality will inevitably reproduce the very inequalities it seeks to avoid. So what is the solution?

According to Schmidt, a program of vaccine rationing that takes social justice as its starting point must organize itself differently; rather than taking “remaining life years” as an important consideration (one that obviously discriminates against the elderly), for instance, one must give priority to society’s most vulnerable. Ideally, Schmidt argues, lotteries should “be weighed to reflect levels of underlying disadvantage so that worse‐off population groups stand higher chances than better‐off ones. A normatively superior approach would go further by directly prioritizing residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods.” Such a move would be consistent with the call from Madison Powers (a philosopher of ethics) and Ruth Faden (a biomedical ethicist) to center social justice in relation to public health, in a study that deals with the historic failures of health campaigns in the past. As the race for a COVID-19 vaccine accelerates, obstacles to vaccine confidence become increasingly apparent, as do ethical questions dealing with the delivery and distribution of the vaccine. A recent article published in The Conversation notes that vaccine nationalism has already emerged as a significant threat to worldwide rationing and access, particularly to those in the developing world well acquainted with what Paul Farmer characterizes as the “pathologies of power” undergirding the distribution of health resources (162).[i]

As data released by the CDC have confirmed, the coronavirus has followed the pattern of other health crises in disproportionately affecting Black and Latinx Americans. Indeed, subsequent analyses have found that members of these demographics are “three times as likely as white people to become infected with COVID-19 and twice as likely to die.” Despite heightened vulnerability to infection, these groups historically are left out of clinical trials of vaccines, a neglect that groups in the United States are trying to redress by pushing for increased representation of BIPOC in studies. In Canada, where neo-colonial policies continue to inform public health interference and neglect, we need only look to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic for evidence on how Indigenous peoples suffer disproportionately during health crises. While it remains to be seen how underserviced Indigenous communities will fare through the current pandemic, any consideration of vaccine rationing should address these historical imbalances; as numerous experts in the field are beginning to acknowledge, racial injustice is indeed a public health matter.

Domestically, social determinants like gender will also need to be addressed. Since social distancing measures began last spring, innumerable publications have sounded the alarm on how COVID-19 has laid bare persistent gender inequities in our society. Because of gendered expectations or grim realities like the wage gap, many women in heteronormative households have opted or been forced to leave the workforce in order to care for children. With the future unclear, many women have no sense of whether their leaves will be temporary or assume a more permanent nature as the pandemic continues. The implications for gender equality cannot be overstated. In households in which both parents continue to work from home, mothers statistically assume the bulk of childcare responsibilities. With another school year set to begin, working parents contemplate a division of labor that looks increasingly binary.

However, for many of us, the power to choose is itself a function of privilege, which is why an exclusively gender-based approach to vaccine distribution can be problematic. As Nessa Ryan and Alison El Ayadi explain, “Women are not a homogenous, static group, and utilising a gender lens alone without understanding of other structural factors can obscure the various other forms of oppression that intersect to create multiplicative disadvantage” (3). An intersectional analysis attentive to the interlocking axes of oppression individuals face illuminates how racialized women, or those who belong to the LGBTQ community or have disabilities, are particularly affected by the gender inequality that inflects their lived experience of the pandemic. In this respect, Harald Schmidt’s call for social justice considerations to drive COVID-19 vaccination campaigns makes a good deal of sense, but centering gender issues through this intersectional lens seems particularly urgent.

Of course, much of this discussion presupposes that vaccine confidence will be firmly in place by the time a vaccine becomes available, but there is no indication that this will be the case. Drawing upon a well-established anti-vaccination movement, resistance to an as-yet-hypothetical vaccine (or multiple vaccines) for SARS-CoV-2 has solidified in recent months, gathering strength from protests of mandatory mask wearing. Rallies outside capitol buildings across North America afford a preview of what COVID-19 vaccine rejection in its most extreme form might look like. The carnivalesque spectacle that typifies these gatherings prevents us from seeing (or gets wrongly conflated with) a milder form of skepticism that circulates amongst certain segments (often white, middle-classed and university educated) of the population. This hesitancy is often identified with mothers who retain responsibility for medical decision-making in the family. In her work on the rise of contemporary vaccine skepticism in the United States, Elena Conis illustrates how twentieth-century feminist medical activism fought hard for the rights of mothers to control what went into their children’s bodies. Even though women opposed to vaccination often aligned themselves with more traditional lifestyles and expressions of femininity, there is a palpable sense in which the complexities of self-determination and bodily autonomy are entangled with vaccination discourse. If the anti-vaxxer rhetoric swaying the hesitant is to be countered, these ideological entanglements need to be parsed and addressed.

A complicating factor is the skepticism around public health that centuries of medical experimentation on diasporic Africans has inevitably helped cultivate. In Canada, distrust of the medical establishment also has deep colonial roots; our hideous equivalents of the Tuskegee and Henrietta Lacks experiments were perpetrated on Indigenous children in the Residential School System and on reservations. Vaccine hesitancy in marginalized communities has received relatively little attention given the high profile of white women amongst those who are hesitant or hardened anti-vaxxers. The trend towards “Karening” the vaccine-hesitant on social media denies visibility to Black and Indigenous people and effaces the legitimate grounds that many in these communities have for mistrusting public health. Recently, volunteers for COVID-19 vaccine trials have expressed a hope that their involvement might help counter vaccine hesitancy in their communities and render more visible the complexities of this stance.

For the reasons outlined above (and others we haven’t begun to consider), we should be wary of assumptions that the same people disadvantaged by prevalent structural inequities will embrace a vaccine putatively enabling them to re-enter the workforce or regain a degree of autonomy. A two-pronged approach will be needed, involving:

1) a concerted effort to address vaccine hesitancy (which has already been exacerbated by the hyperbolic branding of vaccine operations in the US as “Operation Warp Speed”) in a way that addresses responsibly and compassionately concerns of those who identify themselves already as hesitant.

2) a subsequent vaccination campaign that takes social justice as its core principle and offsets the structural inequities built into our healthcare systems.

How are the two intertwined? In the public imagination, vaccination does not equate with social justice. As an arm of the biopolitical regulation of bodies, public health campaigns raise hackles in a culture as steeped in individualism as that of the US (and to a lesser extent, Canada). Choice is often understood as the power to abstain, to opt out of a medical intervention with unquestionable benefits for Big Pharma. For this reason, people must see the value of choosing vaccination, both for themselves and in the spirit of collectivism. The role that popular culture and social media might play in shifting these perceptions aligning public health with the dissolution of individuality and freedom of choice cannot be overstated. Films like Contagion, with which I began this discussion, inform our public health literacy and expose our assumptions about health equality (Kendal).

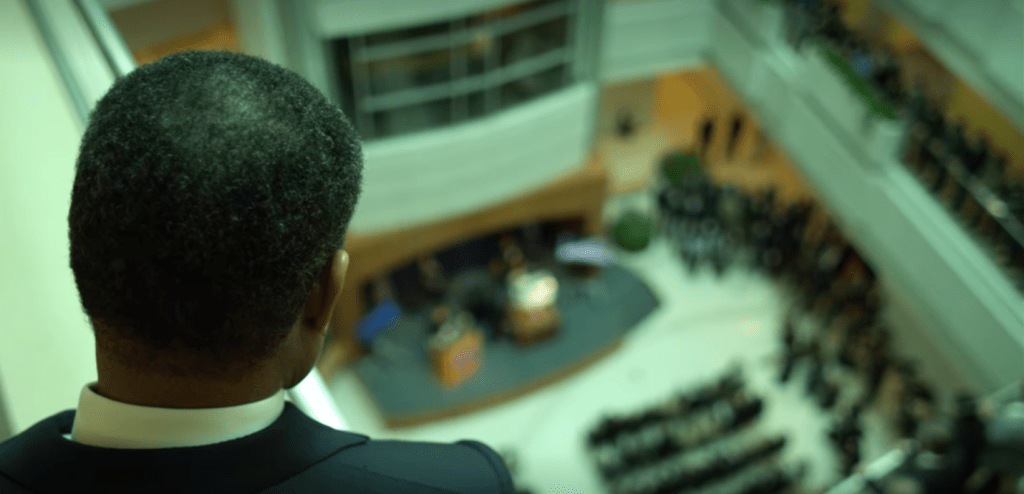

In closing this discussion, I would like to return to the film. Despite the assumptions of vaccine compliance that govern its resolution to the pandemic (the sole objector is portrayed by a white male character ultimately exposed as a profiteering opportunist), Contagion does call attention to problems of access created both on a global scale by nationalistic vaccine rationing and domestically by entrenched intergenerational poverty. A closer look at the film reveals ways its narrative at times subverts the system of the lottery. Towards the conclusion, Dr. Cheever, the CDC official (played by Lawrence Fishburne) who earlier in the narrative violates public health protocol by privately warning his fiancée of the impending lockdown, once again goes rogue by giving his own intranasal vaccine to the son of a custodian working in his CDC building. An act that cuts across class and racial lines, the sacrifice demanded of the racialized character—Dr. Cheever is a Black man while the custodian and his family are white—sits somewhat uneasily. At the same time, as a gesture made by a high-ranking member of a preeminent institution of public health, Cheever’s gift of the vaccine questions the system from within. In fact, his action is on a continuum with other heroics on the part of the film’s scientists, including Dr. Hextall’s self-injection of an experimental vaccine and Dr. Orantes’s sacrifice of her freedom to ensure her captors receive a vaccine that is not a placebo. This persistent rule breaking suggests that the air of efficiency surrounding the vaccine lottery is simply a façade, and that social justice is carved out by the infractions of individuals refusing to comply with a system whose shortcomings they know intimately. Ultimately, however, these transgressions leave the system intact when what is called for is an overhaul of public health systems that do not serve people equally.

[i] According to Karina Gould, the Canadian international development minister, Canada is trying to push back against vaccine nationalism while trying to secure its own supply.

Works Cited

Conis, Elena. “A Mother’s Responsibility: Women, Medicine, and the Rise of Contemporary Vaccine Skepticism in the United States.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 87, no. 3 (2013): 407-35.

Farmer, Paul. Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor: with a New Preface by the Author. University of California Press, 2005.

Greenberg J, E. Dubé and M. Driedger. “Vaccine Hesitancy: In Search of the Risk Communication Comfort Zone.” PLOS Currents Outbreaks. no. 1 (Mar 3, 2017) doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.0561a011117a1d1f9596e24949e8690b.

Kendal E., “Public health crises in popular media: how viral outbreak films affect the public’s health literacy.” Medical Humanities. 19 January 2019. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2018-011446

Powers, Madison and Ruth R. Faden. Social Justice: The Moral Foundations of Public Health and Health Policy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Ryan, Nessa E, and Alison M El Ayadi. “A Call for a Gender-Responsive, Intersectional Approach to Address COVID-19.” Global Public Health, July 7, 2020, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1791214.

Contributor bio: Kelly McGuire is an Associate Professor at Trent University and Chair of Gender & Women’s Studies. Her book project is on gender and the medicalized body, and an internal grant funds her current research exploring debates forming around the COVID-19 vaccine through the lens of history and gender

Images: Stills from Contagion, directed by Steven Soderbergh (2011).