Lakshmi Krishnan and Anna Reisman //

Soon after our universities went virtual due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a medical student approached one of us to talk about Dr. Bernard Rieux, the doctor-protagonist in Albert Camus’ The Plague (La Peste, 1947). “Do you relate to him?” she asked. Rieux describes fighting the plague as an act of “common decency” and labors stoically to reverse its devastating progress in his Algerian town of Oran; many of us caring for patients with COVID in the earliest weeks were, in contrast, perturbed, anxious, and anything but calm.[1]

Although Camus’ depiction of placid epidemic doctoring might not resonate with everybody, we find his rendering of the pandemic’s dramaturgic form as a social—not just biomedical—phenomenon to be deeply compelling.[2] Camus traverses accustomed territory—early disquiet, ubiquitous denial, increasing fear, and the struggle to conquer oncoming waves. There’s enough that’s relatable, both psychologically and socially (as when the pandemic curve veered upward in New Haven and Washington, DC/Maryland in spring, and now once more). The emotions are familiar, as are enduring concepts like food shortages and profiteering, worsening spread in prisons and other vulnerable spaces, quarantines and social isolation, urgent searches for a cure, hospitals shutting their doors to visitors, truncated funerals, and essential workers at increased risk. This very familiarity renders The Plague a useful framework for assembling our own interpretation of current events, events unlike anything that most of us have experienced before this year. As Oran’s citizens proceed through rhetoric and reluctant admission, explanation and etiology, and collective response and organization, The Plague also helps us to navigate uncertainty and anticipation of a potentially more devastating future while providing a glimpse into one way the pandemic might end.

If pandemic fiction such as The Plague and other novels like Mary Shelley’s Last Man, José Saramago’s Blindness, Ling Ma’s Severance, and Colson Whitehead’s Zone One can speak so powerfully to our present moment, this invites a further question. Can the humanities, particularly the medical humanities, play an essential role in our response to a pandemic? The novel coronavirus is spurring necessary action in the scientific and medical communities, but much less has been published in the clinical medical literature about the “applied” humanities. Biomedicine may be overlooking the global repository of historical, contextual, and creative knowledge and skill that live in the humanistic disciplines. With burgeoning technical and scientific requirements, undergraduate and graduate medical education contain little curricular room. In this context, we often mistakenly view the humanities as a “bench science” divorced from our “translational” realities, or an indulgence lacking clinical relevance.

But as COVID-19 forcefully demonstrates, health crises are also transdisciplinary ones. They uncover social ills with precision, as our national reckoning with racism, income inequality, and health disparities continues to reveal. Without attention to the intersections and contingencies driving their outcomes, biomedical interventions are incomplete. Take, for example, the anticipated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The technical acumen and scientific skill required to produce, safely administer, and deliver it are substantial. Nonetheless, these efforts will be meaningless unless we enable its implementation and equitable distribution. In minority communities, for example, distrust of public health interventions is founded upon a chronicle of unauthorized experimentation and unethical research practices.[3] Critic Fredric Jameson remarked, “History is what hurts.”[4] This history is alive and enduringly painful. It will tangibly inform the ways vulnerable populations respond to the novel coronavirus vaccine. Without a grounding in medical humanities topics, such as the history of racism and ableism in medicine, constitutive of and contributing to health disparities, as well as research and clinical ethics, this bioscientific intervention is limited from the outset.[5] But with acknowledgement and careful explication of specific histories, context, and the nuanced outcomes of past interventions, there is great potential to offer thoughtful public health communication and dictate relevant policy.

This is just one example of how the humanities are fundamental to our pandemic response, from shaping health policy and health communication to allocating resources, alleviating health disparities and caring for vulnerable communities, fighting xenophobia and racism, understanding experiences of illness and suffering, providing a source of comfort, and imagining and creating a post-pandemic world together.[6]

In a plague, our destiny is both collective and not collective. The medical student who wanted to discuss The Plague was particularly struck by Camus’ whitewashed portrait of colonial French Algeria. Where were the Arab citizens of Oran? Why were the named characters all European? What implicit structures of data collection and interpretation does that reinforce, even in a fictional outbreak? Who experiences Camus’ plague? Whose stories are elided? And who gets to tell the story of Oran and its people? What started as a conversation germinated research questions, intellectual exchange, reflection, and a critique. This critical aspect, to us, is at the heart of the medical or health humanities, and precisely what allows the field to be pragmatic and collaborative.[7]

Beyond problem-solving, the humanities provide a way to envision alternatives and imagine distinct futures. We are overloaded with information and disinformation. Hungry for ways to interpret our experience, we turn to the humanities as a means to record and metabolize it, as well as shape it. Octavia Butler once described discovering Robert Heinlein’s categories of science fiction stories: “what-if,” “if-only,” and “if-this-goes-on.”[8] Captivated by the third, she drew on her growing concern about contemporary events—racial injustice, ecological ruin, a rampant carceral system, and corporate might—to write Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). They imagine an “if-this-goes-on” America in 2024, violent and profoundly imbalanced, told through the perspective of a preternaturally bright and capable teenager, who projects a world of “what-if”: what could be. Clinical medicine is also imaginative: when we diagnose and treat, recommend preventive health, investigate and plan large-scale clinical trials, we seek a better future. Aspiring to health for all people and imagining a more just world are central to our mission.

Other speculation assumes myriad forms. Like Dr. Sayed Tabatabai, a nephrologist who has become well known for his storytelling about a post-pandemic world, many health care workers have turned to social media, micro-stories, audio diaries, visual and performing art—narratives across genre and media, in order to conjure meaning and possibility out of these overwhelming events.[9] [10] A Yale School of Medicine elective for medical, nursing, and public health students assembled historians of medicine and clinicians to explore and create within this crisis: projects included multimedia journals, “a-day-in-the-life” videos, the history of racism toward Asian-Americans, fictional accounts of contact tracers, and records of living as a Black person during the pandemic.[11] At Georgetown, undergraduates and medical students are co-enrolled in a Pandemics medical humanities course, sharing their perspectives as a generation coming of age during a historic pandemic.[12] [13]

COVID-19 has challenged our medical expertise and laid bare the transdisciplinary nature of our problems. Through reflecting upon and interrogating processes and practices that we take for granted, the humanities can offer specificity and critique that is invaluable for the biomedical sciences. As a means of examining ourselves, our profession, and the broader social context, they shed light on issues traditionally pushed to the sidelines. They also allow us to imagine alternate futures. Collaborating with and learning from humanists can help us carve innovative pathways through the problems which face us, not only as healthcare providers, but as a society.

Author bios:

Lakshmi Krishnan, MD, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Medicine and Affiliate Joint Faculty in English at Georgetown University, where she directs the Georgetown Medical Humanities Initiative. Her work appears in The Lancet, Annals of Internal Medicine, Literature and Medicine, Modern Language Review, and elsewhere.

Anna Reisman, MD, is Professor of Medicine at Yale School of Medicine where she directs the Program for Humanities in Medicine, the Yale Internal Medicine Residency Writers’ Workshop, and co-directs the Program for Art in Public Spaces. Her essays and articles have been published in The New York Times, Washington Post, Slate, Discover Magazine, the Atlantic, New England Journal of Medicine, JAMA, and elsewhere.

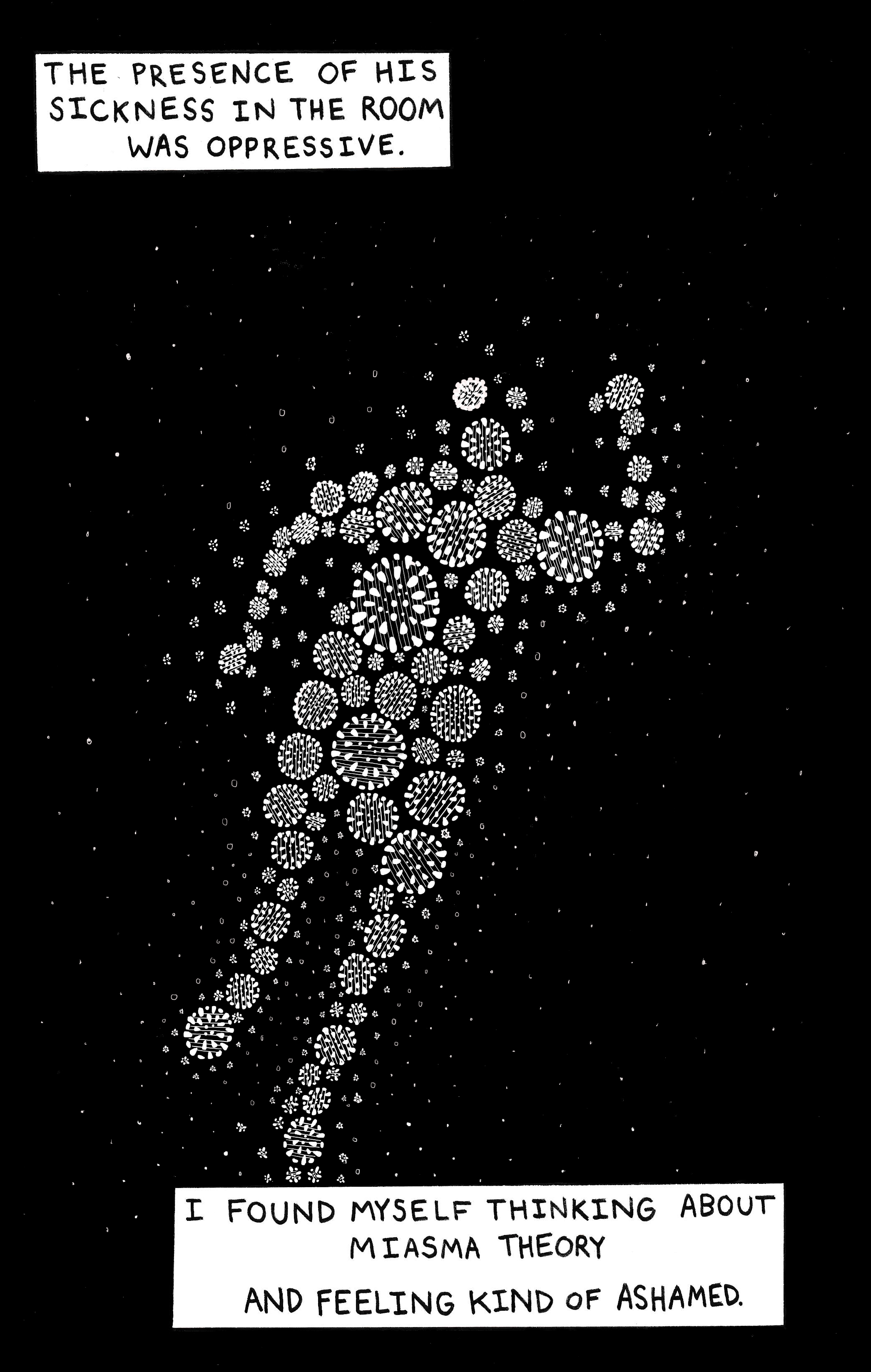

Artist bio: Simone Hasselmo is a Yale medical student and comics creator. Her work First Spring can be downloaded in full for a $5 donation to New Haven mutual aid at seshcomix.bigcartel.com.

Image source: Panel from Simone Hasselmo’s graphic memoir First Spring, shared with permission of the artist.

[1] Camus, Albert, 1913-1960. The Plague. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

[2] Rosenberg, Charles E. “What Is an Epidemic? AIDS in Historical Perspective.” Daedalus 118, no. 2 (1989): 1-17. Accessed July 29, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20025233.

[3] Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Doubleday, 2006; Owens, Deirdre Cooper. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017; Reverby, Susan M., Examining Tuskegee : The Infamous Syphilis Study and Its Legacy. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

[4] Jameson, Fredric, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as Socially Symbolic Act. New York: Cornell UP, 1981.

[5] Krishnan, L., Ogunwole, S. M., & Cooper, L. A. (2020). Historical Insights on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, and Racial Disparities: Illuminating a Path Forward. Annals of Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-2223.

[6] Peckham, R. (2020). COVID-19 and the anti-lessons of history. Lancet (London, England), 395(10227), 850-852. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30468-2; Sinha A. King Lear Under COVID-19 Lockdown. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1758–1759. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6186

[7] Adams, Zoe; Reisman, Anna MD Beyond Sparking Joy: A Call for a Critical Medical Humanities, Academic Medicine: October 2019 – Volume 94 – Issue 10 – p 1404 doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002871.

[8] Butler, Octavia. “The Devil Girl From Mars”: Why I Write Science Fiction. Discussion at MIT, February 19, 1998. https://www.blackhistory.mit.edu/archive/transcript-devil-girl-mars-why-i-write-science-fiction-octavia-butler-1998. Accessed Online Aug 7 2020.

[9] https://www.npr.org/2020/07/19/892757810/texas-doctor-tells-story-depicting-a-future-after-covid-19

[10] http://thenocturnists.com/podcast

[11] https://medicine.yale.edu/news/yale-medicine-magazine/history-of-the-present/

[12] https://gufaculty360.georgetown.edu/s/course-catalog/a1o1Q000003MZb0QAG/idst13501?id=0031Q000021akncQAA

[13] Pandemics Course Blog: https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/pandemics-fall2020/; Class Twitter: @Pandemics20