Timothy Kent Holliday //

“Dying is an art, like everything else” (Plath 245). With these words twentieth-century poet Sylvia Plath alluded to her own suicidal ideation. Death wishes of a different kind entwined in cities like Philadelphia in the 1830s, a century before Plath’s birth: the dying dreams of a patient, and the nineteenth-century anatomist’s desire to study the dead. That year, a terrifying and largely incomprehensible disease ravaged much of the Eastern Seaboard, having already wreaked its havoc from Sunderland to the Sunda Islands—that is, England to Indonesia—and, years before, the Gangetic Plain of the Indian subcontinent.

The disease was cholera. Or, put another way, cholera was the disease. In the 1830s, it was often called by physicians the epidemic, Asiatic, malignant, or spasmodic cholera, to distinguish it from cholera morbus, or gastroenteritis. What made cholera so horrifying can be summarized as a combination of three factors: the unpredictability of its geographic spread, the totality of its influence over the body, and the rapidity of its progression in each individual case. There was no telling where cholera might pop up. Cholera sprung grasshopper-like from city to city, first appearing in Basra the same year it reached Beijing. Dr. Samuel Jackson of Philadelphia likened cholera to a scald that covered the entire skin: it affected first and foremost the alimentary organs, which Jackson compared in surface area to the skin itself. The alimentary organs were linked to the bronchial organs, as well as the cerebro-spinal and ganglionic nervous systems. It was anatomists like Jackson who most elegantly articulated the frightening totality of cholera’s effects on the body. Cholera was “gastritis, duodenitis, enteritis, and colitis,” Jackson wrote, “at one and the same moment” (Jackson 341). Disturbing as it did the entire digestive system at once—and, by extension, the lungs, brain, and spine—cholera took over the patient’s body. Finally, a cholera case could progress with shocking swiftness. To wrest control of the body back to the patient required the utmost diligence of the caregiver. Cholera time was measured in hours, even minutes. Constant vigilance was compulsory.

But, of course, not every patient could be saved. In fact, cholera’s mortality rate was staggering, apparently hovering somewhere between one-third and one-half. In the burned-over psyche of the Second Great Awakening, cholera inspired holy terror. Worldlier accounts read like body horror. “I speak of it as gallons,” wrote physician Hiram Corson, of patients’ diarrhea. “Dr. Jackson said he had seen bucketfuls discharged in a few hours from the bowels alone” (Corson 5). One patient told Jackson that “he felt as thoug[h] his whole body was coming through his bowels” (Jackson 315).

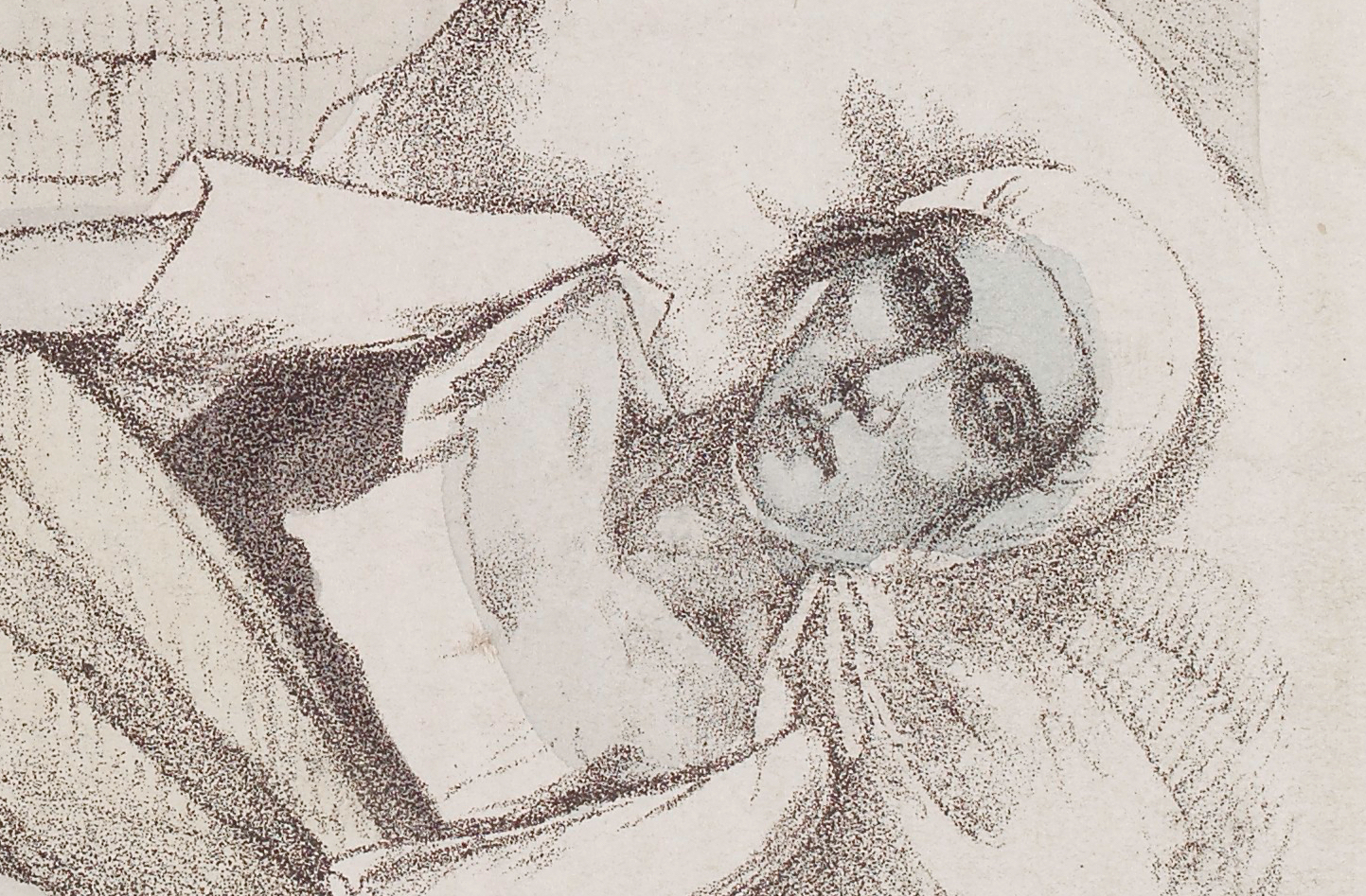

Oftentimes a patient’s condition became more intimately known only when, as a medical student put it ten years before cholera’s appearance in Philadelphia, “elucidated by the scalpel,” following the patient’s death (Jones n.p.). The same was true during the time of cholera. “Having taken a piece of intestine home and hardened it in alcohol,” wrote southern-born Philadelphia physician William Horner in 1835, he could prove “beyond controversy” that its membranes had thickened. (Horner, Anatomical Characters, 13). Satisfied, he placed the jejunum with the rest of his anatomical specimens. An image accompanies Horner’s description of the piece of intestine, preserving the violence of Horner’s careful curiosity like soft tissue in formaldehyde. Horner took the piece of intestine from the body of Jacob Myers, “a black man, aged thirty-six years, of a make somewhat robust,” who died of cholera in Philadelphia’s Blockley Almshouse in September of 1834 while being treated for a scrofulous tumor (Horner, Anatomical Characters, 13). In the early 1830s, physicians like Horner used the bodies of living and dead patients like Myers to better understand the terrifying new disease of cholera. Medical knowledge production during the time of cholera thrived on the violent methodologies of early clinical epidemiology.

Myers was but one of countless of Horner’s patients, always already specimens-in-waiting as Horner busied himself with the task of amassing a vast collection of anatomical specimens while cholera beset Philadelphia. Just a couple years prior to his theft of Myers’s jejunum, Horner had served as the presiding physician over Cholera Hospital #3, located close to the banks of the Delaware River. Hospital #3 accommodated some twenty-seven patients between July 25th and August 20th, 1832. At any given time, there were only about three or four patients in the hospital, though at times as few as one and as many as seven. One of the patients, a thirty-five-year-old Black man named Littleton Tacle, entered the hospital on August 6th. That evening, thirty-three-year-old white man Anson Evans, who worked as a waterman and was the hospital’s only other patient at the time, died. No other patients entered the hospital for the remainder of Tacle’s time there. This might have been the closest thing to private care that Tacle had ever received from a white physician.

Horner’s case notes for most of his patients in Cholera Hospital #3 are remarkably detailed, and his careful attention to the particularities of Tacle’s case is perhaps ultimately unsurprising, especially since there were no other patients in Hospital #3 at the time. Nevertheless, it is striking that, less than five hours before Tacle’s death, Horner noted that Tacle “says he was dreaming when I awoke him, of home in Va &c.” (Horner, “Case Book,” 13). What prompted Horner to make note of this? The association between cholera and Blackness refracted intimacy between caregivers and patients through a racial lens. Scrutinizing case notes to establish the relationship between a white physician and his Black patient requires, to some degree, speaking in the frustrating language of perhaps. Horner himself had grown up in Virginia; maybe he felt some connection to Tacle due to their shared home state. Whatever other thoughts he may have had, Horner likely interpreted some sort of clinical significance in Tacle’s dream. Maybe it was evidence of Tacle’s lucidity: he “says he was dreaming,” and thus distinguished his dreams from reality. Or maybe “dreaming” was Horner’s word—maybe Tacle believed himself to be back home in Virginia—and the note was meant to show Tacle’s delirium as he approached death. Since Horner was an anatomist and an avid collector of wet and dry anatomical specimens, there is no reason to categorically deny the possibility that Horner took a portion of Tacle’s body and put it in his Anatomical Cabinet, just as he later would with Jacob Myers. This was the upshot of nineteenth-century anatomical science. Its logic, to paraphrase artist and social theorist Johanna Hedva, required that some patients die. (Hedva n.p.)

WORKS CITED

Corson, Hiram. Reminiscences of the Cholera Epidemic of 1832: And Notes on the Treatment of the Disease at That Time. Philadelphia, Pa.?: np, nd. Reprinted from The Philadelphia Medical Times, 9 Aug 1884.

Hedva, Johanna. “Sick Woman Theory.” Mask Magazine, 2016.

Horner, William E. “Case Book: August 1832.” 10a 355. Historical Medical Library. College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, Pa.

Horner, W[illiam] E. On the Anatomical Characters of Asiatic Cholera, with Remarks on the Structure of the Alimentary Canal. Philadelphia, Pa.: Joseph R. A. Skerrett, 1835.

Jackson, Samuel. “Personal Observations and Experiences of Epidemic or Malignant Cholera in the City of Philadelphia.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 22 (Feb 1833): 289-345.

Jones, Samuel. “The Causes, Nature, Symptoms, and Treatment of the Endemic Fever Which Prevailed in the City of Philadelphia During the Summer of 1820, Exhibiting a Pathological Division of the Yellow Fever into Four Distinct Classes, with the Diagnostic Signs, & Treatment, Appropriate to Each” (1822). 378.748 POM 16.1. Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts. University of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, Pa.

Plath, Sylvia. The Collected Poems. Ed. Ted Hughes. New York, N.Y.: HarperPerennial, 1992.

Image source: Blue stage of the spasmodic Cholera of a girls who dies in Sunderland, November 1831 [Cropped]. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)