Sara Press//

Every person pictured has consented to having their portraits shared publicly.

In 2009, Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie gave a TED Talk on “The Danger of a Single Story.”[1] In her talk, Adichie advocates for the importance of storytelling, but cautions against homogenizing complex humans and situations into a single narrative. She explains, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.” Adichie’s warning reflects her own experience of moving to the U.S. at age 19 and realizing that people had pigeonholed her based on reductive stereotypes about people from Africa. Adichie’s TED Talk speaks to the danger of a single story, but also to the power of being in control of one’s own narrative. Through storytelling, we can dispel stereotypes based on signifiers like class, gender, race, and illness, which diminish the richness of our lives.

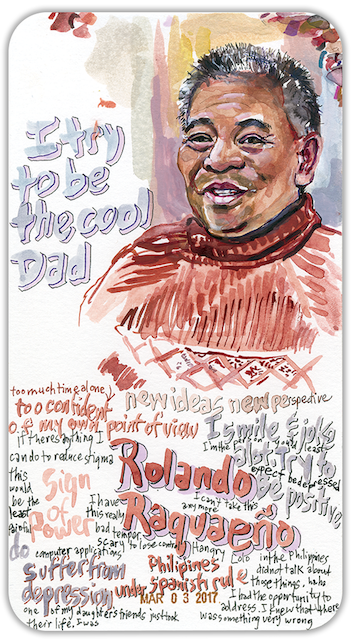

Although her own story is quite different from Adichie’s, Canadian-born performance artist Charmaine Wheatley is equally invested in showcasing the multiplicity of human experiences and identities. Wheatley’s art confronts the consequences of a single story by using drawings and watercolors to animate life. Her compositions reflect intimate moments between Wheatley and her sitters, capturing physical likenesses and fragments of conversation. Wheatley’s pocket-sized portraits offer a glimpse into the struggles and joys that each individual carries with them.

Wheatley holds a life-long residency at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston and is an Artist-in-Residence at the University of Rochester Medical Center and the University of Buffalo, both in the state of New York. Her work in Rochester and Buffalo has involved sitting with over two hundred people from vulnerable communities, predominantly those affected by mental illness and HIV/AIDS. “De-stigmatizing happens through humanizing,” Wheatley explains.[2]One of her former sitters described the experience of being painted, saying simply, “She heard me.”[3] For many of those who are medically marginalized, Wheatley’s portraits offer a unique opportunity to be seen as a person rather than a disease or statistic.[4]

Wheatley and I met at a Health Humanities Conference in Chicago in March of 2019. Approaching the conference sign-up table, I was distracted by a large poster with bright watercolor portraits surrounded by words. A television positioned beside the poster showed an exuberant artist painting and listening attentively to her sitter. That artist was Charmaine Wheatley, and she happened to be standing right beside the image of herself on screen. We immediately fell into conversation and have stayed in touch since.

In February of 2020, COVID-19 hit the U.S., and by March, the country—and most of the world—was in lockdown. Confined to our respective quarantines, Wheatley and I talked over Zoom about some of the big questions we were both grappling with: How had the pandemic affected peoples’ lives differently? How could we share those experiences through art? Throughout this discussion, it turned out, Wheatley was painting a portrait of me. I suggested having another Zoom call where Wheatley paint herself while I propose fragments of our conversation to be incorporated into her self-portrait.

During Wheatley’s self-portrait session, we decided to reach out to people online to do more Zoom portraits. This could be a way of making new social connections in quarantine, to hear from people whose stories of the pandemic may not yet have been heard. We began to reach out to people through our networks to find individuals we had never met, but with whom we were somehow connected.

Wheatley held virtual portrait sittings over the summer of 2020, during which she talked to sitters about how their lives had been affected by the pandemic. New York City native Kerim Eken contracted COVID-19, along with his wife and infant daughter, in the spring of 2020, at the height of infection in NYC. The weekend they tested positive, Kerim’s family was planning to move to a new apartment in Brooklyn. His father, visiting from Istanbul, was also infected with COVID-19 during this time and was forced to stay in the U.S. for five months due to travel restrictions. Fortunately, Kerim and his family all recovered. Many others have not.

Wheatley also spoke with health experts to hear from people experiencing a different side of COVID-19. Dr. Tom Evans, an Infectious Disease doctor and researcher based out of Oxford, England, was working in Boston at the time of this portrait in May of 2020. Evans is one of the many front-line workers who has been treating patients in COVID units throughout the pandemic. Evans told Wheatley that he felt fortunate to have more personal contact than most, since he was treating the homeless three nights a week after his regular shifts in the hospital. Evans’ portrait offered insight into the human connections that healthcare workers were making in the midst of a health crisis and nationwide lockdown.

Throughout the pandemic, Wheatley has adapted her art according to shifting social and political needs. Last May, many of us witnessed the video of George Floyd’s murder— a brutal reminder of the parallel pandemics plaguing the United States: anti-Black racism and systemic inequalities. These forms of structural oppression have been exacerbated by the pandemic, leading to disproportionately higher COVID-19 infection rates and deaths among low-income, incarcerated, and racialized communities.

Wheatley spent much of last summer making letterpress and silkscreen posters for the Miner Library collection at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. Following the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and so many other African Americans, Wheatley used her art to draw attention to the racist history and persistent racism in Rochester (named after slave owner Nathaniel Rochester). Wheatley’s poster below depicts a real statue of Nathaniel Rochester, which became a site of contention last summer, with protesters calling for it to be taken down. It was not. This art was a way of talking back against dominant progress narratives in America.

Wheatley is currently involved in a new project in rural areas of the Eastern and Southeastern U.S., where she is painting portraits of people whose lives have been upended by the opioid epidemic. Her portraits of people affected by this public health crisis, like other work she has done with medically marginalized communities, seek to decrease the stigma of illness. Her art is a reminder that everyone has stories to tell, and they are all worthy of being heard. While her portraits are only glimpses into a person’s life, those fragments give us entry into the complexity of human experience, and remind us never to reduce a person to a single story.

Works Cited

[1]https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

[2] http://artreducingstigma.charmainewheatley.ca

[3] Ibid.

[4] Portraits of Life is the name of a documentary about Wheatley, which you can find here: http://artreducingstigma.charmainewheatley.ca/other-projects/