Michelle Munyikwa //

Several months ago, I spent some clinical time working on a service with patients being evaluated for organ transplantation. Between the complex medical decision-making and challenging social negotiations that entail transplant evaluation, the social issues are infinitely more subjective and fraught. Everything from the substance use histories to the employment history to the housing predicaments of my patients was considered in the decision about whether or not to allocate them one of the organs that are transplanted each year at my hospital.

While our transplant program is comparatively large, the absolute number of each organ transplanted each year is small, meaning each patient selected is chosen to receive one of dozens of that particular organ transplanted each year. As such, the complex apparatus of organ transplantation had many moving parts, of which my personal, daily clinical practice comprised very little. But, as the junior doctor on the team, I was often tasked with routine administrative tasks that would accrue to something consequential, which is how I found myself calling a series of my patient Dante’s former physicians one afternoon at work. In part, I was tasked with this because “social work concerns,” as they were often phrased, had arisen in the course of evaluating Dante for potential transplant listing.

One after another, I dialed the numbers of everyone we knew of who had ever cared for him, and the results were disheartening:

“I think he means well, but he really just isn’t able to come to appointments. We never were really able to figure out why, but after he failed to follow up with his lab draws we had to take him off the transplant list. We’re a small program, and it was too much of a risk.”

“I loved Dante and his family, but he never came to his appointments.”

“Dante is great, but he struggles to adhere to therapy and never took his meds. He never could quite make it work.”

Each clinician painted the picture of someone who “meant well,” but who wouldn’t quite be up to the task of care coordination that a transplant necessitates. His physicians liked him, but they didn’t believe in him. Dutifully, I wrote these reports down, but they troubled me. I knew they didn’t bode well. I was particularly troubled because I had grown fond of Dante in the days that I had been taking care of him. He was kind, and I felt for him; I recognized the smile in the corner of his eyes when he spoke about his kids, and I saw the tenderness between him and his mother. He had been through a lot. At the same time, he had had increasingly tense confrontations with members of the team. The condition which had caused his organ failure had given him many complications along the way, including chronic pain which, through a series of events, had come to be treated mainly through large doses of Dilaudid. He had long been dependent on the medication to get through the day without excruciating pain, but as a Black man he faced an even higher level of scrutiny in those needs than he would have otherwise. It produced an incredible amount of conflict in an already high stakes relationship, and we had daily conversations about his pain regimen.

Getting the organ would change the trajectory of his life. He was young and otherwise healthy enough to expect to live another 30 years with his organ transplant. The physicians I’d spoken to had refused to list him, and he’d come to us for a second opinion and another chance at receiving the surgery that would change his life. Reporting the news from his prior physicians to my team worried me; I knew it wouldn’t bode well, and the next morning on rounds our attending said as much. As we all stood as a team in the room he matter-of-factly reported Dante’s reputation back to him, stated more or less as fact. Before he had a chance to respond in full, we were gone, off to see another one of our patients.

Later, I was called back to his room, where I found him in tears. He and his mother wanted me — wanted us — to know that we had made them feel worthless. We had written him off because he had been poor, because he had experienced homelessness, because he hadn’t always had enough — time, space, money — to be the model patient. They felt we’d also written them off at least a little because they were Black. This last point stuck with me for a while, because I knew in my heart of hearts that his Blackness did, indeed, have a lot to do with it. At the same time, what was experienced primarily as interpersonal racism — the cold stare of a team of masked doctors, questioning his commitment and not waiting for a rebuttal — stemmed from something that both acted through our will and exceeded our volition. As the primary barrier between him and the organ that would give him life, we represented a bigger process which instantiates structural bias so deeply into its core that physicians enacting it don’t have to be “racist” or exhibit “implicit bias” in order to do harm, but rather buy into the myth of objectivity through rationality and deploy criteria which are necessarily exclusionary, selecting for wealth, socioeconomic stability, and socially-constructed desirability. As I found myself explaining to Dante that day, we were only doing our due diligence – dotting our i’s, crossing our t’s. In other words, finding a way to distribute an organ equitably.

I left dissatisfied, though we had come to an understanding by the end of the conversation. I reassured him that, contrary to how we had made him feel, we were still considering him for transplant. Ultimately, Dante received his organ, much to my and his relief. Even so, I still felt unsatisfied.

While the discourse of anti-racism in medicine is profoundly useful, much of it focuses heavily on the problem of individual physician bias, particularly implicit bias, and its role in producing health inequities through disparate care. Without a doubt, this problem is rampant in medicine and is receiving the attention it deserves at this moment. That being said, I wonder how this focus on the transformation of individual sentiment may cause us to fall short of enacting justice for our patients and communities.

In the last segment of his compelling ethnography Against Humanity, Sam Dubal articulates an anti-humanist praxis of medicine which is particularly resonant with the problems I and others have faced in attempting to think ethically about the practice of delivering care. He notes a particular tendency towards focusing on humanist practices in medicine which emphasize an attentiveness to individual patients and their suffering, as well as individual relationships of care between patients and their providers. I will admit, sheepishly, to an adherence to this form of humanism — that humanism which would see in my interaction with Dante a kind of care; the moment of listening, of recognition of harm, and of the transformation of the space of care between us. In many ways, it is satisfying to frame this as the primary ethical obligation we have to our patients. But, as Dubal notes, that emphasis on sentiment often overshadows and sometimes even forecloses the enactment of other practices of justice. In other words, “one can try to be more kind and loving toward patients, yet still function as a reformist corporate bureaucrat unable to see the forest for the trees, fixated on individual instead of collective good” (222) [1].

In reflecting upon Dante and other patients like him, I’ve come to think that we must, ultimately, think of care and justice together, perhaps through what Miriam J. Williams describes as “care-full justice,” which entails a deeply contextual and embedded practice of attempting to enact mutually constituting care and justice together [2]. Thinking through care-full justice helps us care as one way in which to enact a just future through quotidian interactional practices of relation, and is among one of the ways I’m trying to think through the ethics of both medicine and scholarship (in my case, anthropology) alike. Thinking through care-full justice means thinking critically about what justice means and about whether our practices of care enable injustice, and about how to care through fundamental reorganizations of that which makes our patients sick. In other words, it is caring to share with Dante what we are thinking and to hear his distress, but it stops short of justice to contemplate our encounter as merely an instantiation of interpersonal racism rather than the outcome of intertwined individual and structural processes that the process of organ listing represents.

In articulating what a more care-full, less bounded form of justice might look like as it could be articulated in the future, I am animated by a few ideas [3]. The first is deconstructing evidence, particularly as it relates to conceptualizing risk and harm and the way these risk metrics have been integrated into clinical practice. In conversations like those had about Dante, how might an attentiveness to the construction of our own empirical judgments, which allow us to witness the impacts of differential biology and social positioning but not necessarily interpret them or act upon them ethically, have shifted our conversations? Secondly, while rigid bioethical frameworks offer one way of thinking through ethics and practices of care, how might integrated practices of care-full justice allow us to reframe what the grounded experience of just clinical practice feels like? This attentiveness to affect challenges us to examine the discursive framing of anti-racism in medicine as something which is grounded in sentiment, which at the end of the day is complex because we have to be aware of the ways that “positive feelings” do not alone justice make. So the question is, if it doesn’t always feel “good,” how do we recognize what it means to do anti-racism and thus justice for our patients?

These are the more difficult questions with less easy answers, and I think they have a lot to do with recognition of the complex personhood of our patients – and, as such, both their positive and negative traits – as well as our own, to really grapple with our mutual embeddedness in a society which seeks to separate us.

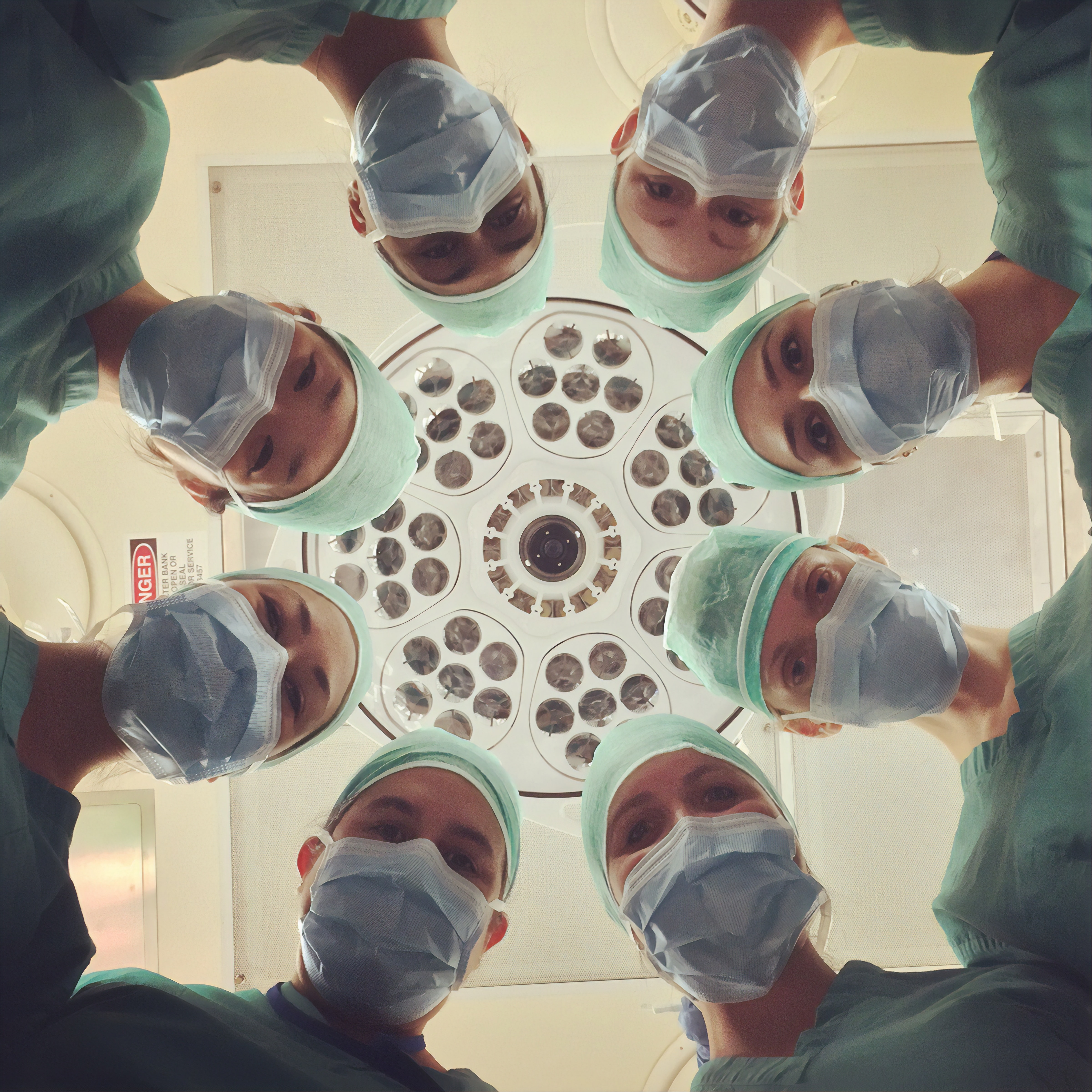

Image source: National Cancer Institute (NCI), via Unsplash, free to use under Unsplash license.

Works Cited

[1] Dubal, Sam. Against Humanity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018.

[2] William, J. Miriam. “Care-full Justice in the City.” Antipode. August 17, 2016.

[3] Creary, Melissa S. “Bounded Justice and the Limits of Health Equity.” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. June 29, 2021.