Emily Waples //

This year—the most difficult year of my professional and personal life to date—I inherited a class called “How We Die.” Offered as part of my college’s Biomedical Humanities major, as well as fulfilling an “ethics and social responsibility” requirement for our general education curriculum, this four-credit course met for two hours twice a week for twelve weeks. Me, twenty students, and forty-eight hours of death.

The title of the course, of course, is borrowed from surgeon Sherwin B. Nuland’s influential 1993 book of this name, which probes the ethos of death-denial enabled and facilitated by the “method of modern dying,” one that is fundamentally informed by all things biomedical. “Modern dying,” Nuland explains, “takes place in the modern hospital, where it can be hidden, cleansed of its organic blight, and finally packaged for modern burial” (xv). In his popular book Being Mortal (2014), fellow surgeon-author Atul Gawande concurs: “scientific advances have turned the processes of aging and dying into medical experiences, matters to be managed by health care professionals,” Gawande writes; “And we in the medical world have proved alarmingly unprepared for it” (6). As Gawande and others lament, the domain of death and dying has been foisted upon doctors and nurses who are often no better equipped to shoulder its complexities than the rest of us—and in some ways even less so, motivated by and trained in a biomedical culture that emphasizes, even insists upon, the virtues of remediation and cure.

In response to this dearth of death in pre-health professions education, death studies scholars have called for a move to redress the “inadequate attention to death and dying in medical curricula at all levels” (Wass 293), including undergraduate education. Yet death education is not only pertinent to health care professionals, of course, but to all of us who will die—in other words, all of us. The mass death event of the COVID-19 pandemic has rendered this reality all too salient, as recent publications in the journal Death Studies affirm. Noting the “new urgency for advance care planning” catalyzed by the pandemic, for example, one offers the recommendation “that death education be incorporated in the undergraduate curricula of all U.S. institutions of higher education” (McAfee et. al. 1, 3); another anticipates a “surge of complicated grief” (also known as “Prolonged Grief Disorder”) likely to stem from pandemic, arguing for a public health approach that “would start by requiring death education of all undergraduate students, especially those majoring in education and the health professions” (Jordan et. al. 3, 4).

During my career in higher education, I have been party to innumerable academic planning meetings centered on revising and re-envisioning a general education core curriculum for today’s undergraduates. Regrettably, it had not yet been suggested that we number ars moriendi among those nebulous “21st century skills.”

Perhaps we should.

Courses in death and dying have existed in U.S. undergraduate institutions since the 1960s, emerging contemporaneously with field of “thanatology” and bearing the conspicuous influence of thinkers like Dame Cicely Saunders and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (Hasha and Kalich 173). Earlier this year, a Time article took note of the rising popularity of such classes amid the pandemic, pointing to examples like Kean University’s “Death in Perspective” course, which famously boasts a three-year waitlist and was prominently featured pre-pandemic as the subject of journalist Erika Hayasaki’s 2014 book The Death Class.

The waitlist for my own class was somewhat more modest. Still, stepping in to take it on for the first time, I was overcome with imposter syndrome. Who was I to teach this?

I cannot tell you how I stack up vis-à-vis any formal psychological assessment tool, any Death Anxiety Scale like the one first formulated by Donald Templer in 1970, comprised of totalizing true/false statements (The thought of death seldom enters my mind. I very much afraid to die. I am not at all afraid to die). I can tell you that one morning I experienced a full-blown panic attack, sparked by a particular course reading that reanimated my ever-simmering fear of a cancer recurrence. (True or false? I am not particularly afraid of getting cancer.) I can tell you that, teaching amid a surging pandemic, on a collapsing planet, against terror unfolding in Ukraine (True or false? I shudder when I hear people talking about a World War III), it is all I can do to stumble up the stairs to my classroom most days. I can tell you that I hold my children’s small, vulnerable, still-unvaccinated bodies and am overcome with apprehension and grief (True or false? I feel that the future holds nothing for me to fear).

Who should teach such a class?

Kean University’s cours célèbre is taught by Professor Norma Bowe, a registered nurse who holds a PhD in Community Health Policy; at other colleges and universities, death and dying classes are variously housed in departments including Bioethics, Psychology, Sociology, and Religious Studies. My own disciplinary background in English begged a somewhat different approach; if I were going to enter discussions of death and dying every day, I would need to do so through the portal of poetry.

While I was crowdsourcing suggestions beyond Donne and Dickinson, Thomas and Plath, a brilliant poet-turned-palliative care chaplain of my acquaintance (thank you, Joe), offered me the gift of Franz Wright’s “On Earth,” which provided an ideal entry point: “but how / How does one go / about dying?” the poem asks—

Who on earth

is going to teach me—

The world

is filled with people

who have never died

As I contemplated my responsibility to teach my students—to deliver the learning objectives I did not design—the question reverberated: Who on earth is going to teach me?

Thankfully, a community of guest educators answered the call, sharing their own experiences in end-of-life care, offering reflections on lives spent at the bedsides of the dying—from a leader in the field of pediatric palliative care who discussed the development and significance of this specialty, to a hospice social worker who shared her experience organizing the first Death Café in the United States, to a local death doula who helped us facilitate our own campus death café as a final project for the class. If the philosophies of hospice and palliative care are rooted in interdisciplinary collaboration for holistic practice, so too, I think, should a death class be.

The rallying cry for mandatory death education raises questions of not only who should teach such courses, but how they should be taught. Writing in the journal Innovation and Education last year, authors from Emory University detail the results of their pilot interdisciplinary course on palliative care, team-taught by a geneticist, a scholar of American cultural studies, and an undergraduate honors student. They promote a pedagogical approach informed by a “Community of Inquiry model of social, teaching, and cognitive presence,” emphasizing the importance of “building a trusting community, creating a course that values and contextualizes experiences and beliefs, and, undergirding these two, having instructors model and then facilitate effective scholarship” (Kulp et. al. 9). I agree that a death class should be taught this way because I believe that all classes should be taught this way. In teaching this class—that is to say, in being present for and witness to my students’ reflections on mortality, loss, and grief—I am not confident that I succeeded in achieving the syllabus’s articulated outcomes. But I do know that I learned from, and developed a depth of appreciation and respect for my students in ways more complex than I ever have in any other course. I know their fears, their hurts, the names of their dead childhood friends, the last words they spoke to their loved ones.

The engine of this knowledge is narrative. The class, like the earth, was filled with people who had never died—and yet in another sense, it was filled very palpably with people who had. Paul Kalinithi and Julie Yip-Williams and Rosalie Lightning. The past patients my guest speakers invoked. My students’ family members and friends. My stepmother. My brilliant former classmate and colleague, in whose memory I offered Bishop’s “One Art.” My former student, on whose coffin I dropped a carnation last April.

Despite our different professional trajectories—clinics and classrooms—my guests and I shared un understanding of the centrality of narrative. One palliative care physician who spoke with our class had pursued a B.A. in English before entering medical school, and in versed in the theory and practice of narrative medicine. Chatting informally with the clinical lead on the poet-turned-chaplain’s care team, I was struck by her multiple invocations of “narrative,” and asked whether she happened to have a background in the humanities. Oh yes, she said. I was an English major. Burning with curiosity—and now, an embryonic hypothesis—I posed the question to my next physician-guest. She smiled. Her parents were writers, she said.

In addition to narrative, another word that recurred conspicuously in conversations with these guests was honor—it was an honor to accompany patients in their final moments, they said; it was an honor to receive their stories.

I am an imposter, I thought; I do not hold vigil. I only hold office hours. But I, too, am in the business of receiving stories. And this, too, is an honor.

Who on earth is going to teach me?

You are.

You are.

You are.

A note of appreciation: For their example syllabi and intellectual labor, I am indebted to Erin Lamb, Michael Blackie, and Craig Klugman in my development in this course. For their expertise and generosity of time in engaging with my students, I wish to express heartfelt gratitude to Joseph Chapman, Lynn Hermensky, Sarah Friebert, Angela Laakso, Lizzy Miles, and Laura Shoemaker. For my students, being with me in this most difficult and essential of work, thank you. As far as you’ve come / can’t be undone.

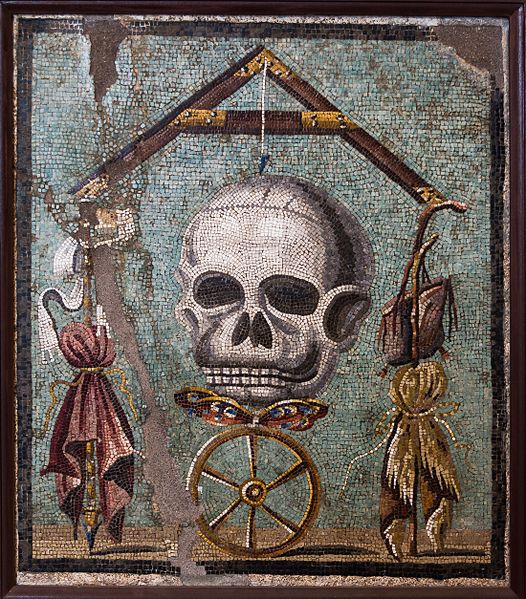

Cover Image: Memento mori. Collezioni pompeiane. Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

Works Cited

Gawande, Atul. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. Metropolitan Books, 2014.

Hasha, Margot, and Deann Kalich. “The Birdhouse Project as Experiential Learning Tool for College Students and Beyond.” Illness, Crisis & Loss, vol.27, no. 3, 2016, pp. 172–189.

Jordan, Timothy R., et. al. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Dying and Grief: Will There Be a Surge of Complicated Grief?” Death Studies, 2021, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07481187.2021.1929571. Accessed 20 Apr. 2022.

Kulp, David, et. al. “Teaching Death: Exploring the End of Life in a Novel Undergraduate Course.” Innovation and Education, vol 3, no. 1, 2021, pp. 1-13.

McAfee, Colette A., et. al. “COVID-19 Brings a New Urgency for Advance Care Planning: Implications of Death Education.” Death Studies, 2020, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07481187.2020.1821262. Accessed 20 Apr. 2022.

Nuland, Sherwin. How We Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter. 1993. Vintage Books, 1995.

Templer, Donald. “The Construction and Validation of a Death Anxiety Scale.” The Journal of General Psychology, vol. 82, 1970, pp. 165-177.

Wass, Hannelore. “A Perspective on the Current State of Death Education.” Death Studies, vol. 28, no. 4, 2004, pp. 289-389.