One summer morning, I found myself in the hollow tube of an MRI. A technician pressed foam earplugs into my ears, gingerly placing oversized headphones on top. The hospital’s artificial breeze rustled my gown. Into the imaging machine I went: face down, breasts out. As contrast dye entered my veins, I tasted metal. A symphony of beeps echoed around me, and then artillery sounds, cutting through the low growl of The National in my headphones. We were in the early months of the pandemic, and I was alone here with the technicians. Despite my best efforts to stay calm, the beeping and whirring kept me startled and awake. I counted the seconds between each new sound. Eventually, the imaging was over, and I exited the machine on a conveyor belt.

“You’re a good patient,” one technician remarked, as I pulled my hospital gown back up.

In the waiting room, patients were scattered and separated from one another. Caregivers were not permitted, per hospital rules. Women visibly in cancer treatment, bearing scarves, wigs, and walkers, chatted quietly with those—like me—in less conspicuous care. My partner picked me up and we drove home.

A few days later, the call came.

“Your left breast was perfectly normal.”

I sensed a but coming.

“But—”

There it was.

“But—there was a suspicious finding in your right breast.”

She shared further details and I wrote them down. The words passed through my ears. My heart was up in my ears, too, pounding, drowning out the words.

“You’ll need to come back soon for a biopsy.”

“Okay,” I said.

*

A few years earlier, when my mother was sick with cancer for the third time, I had genetic testing done and was diagnosed with a pathogenic BRCA1 mutation. The mutation conferred an elevated lifetime risk of breast and ovarian cancer, and since then, knowledge of the gene had slowly sunk in, coloring everything. It inflected how I thought about my life, my relationships, and my career path. It had led me to want to practice as a genetic counselor. Now, the summer was coming to an end, and in a few weeks, I would begin clinical training. The irony struck me: I was about to immerse myself in this thing that was threatening me. What would it mean to start training as a genetic counselor right as this story was unfolding for me and my body? Genetic counselors guide clients through moments of profound uncertainty. What would it mean for my own uncertainty to be waving before my eyes, a thick velvet curtain obscuring the rest of my life from me?

*

At the biopsy, I was poked, needled, cut into. A chip was inserted into my breast. Afterwards, it swelled and hardened, as if materializing the hypothetical tumor. Red lines webbed out around it. I wondered at my own flesh, this extension of me, acting like it belonged to someone else. A week or so later, the next call came, this time from the radiologist.

“It was all normal,” she said.

And so, all normal, I began my graduate training in genetic counseling.

*

Of course, in the realm of cancer care, there is no all normal. In a memoir of metastatic cancer care and loss, The Bright Hour, Nina Riggs writes of medical uncertainty as inhabiting a ‘suspicious country.’ The phrase comes from the sixteenth-century philosopher Michel de Montaigne, who survived the loss of five of his six daughters, the death of his closest friend to the plague, and a lifetime of kidney stones. As for death itself, it is inevitable, Montaigne writes in his Essays. There is no place from which it may not come from; we may keep turning our heads ceaselessly this way and that, as in suspicious country.

“Suspicious Country,” Riggs writes. “I believe I am learning to know that place.”

*

A year or so into my training, I rotated in a high-volume cancer clinic. Many of my patients, like me, had family histories of cancer, and many of them had experienced care and loss. At a sensitive juncture, they were being seen for risk assessment and offered genetic testing. When my supervisors and I talked about the meaning of a pathogenic variant, we presented patients with two options, surveillance or surgery, to manage their risk. We used professional guidelines to steer how we talked about these options, detailing them to patients with clean precision. But in the encounter between myself and the patient, supervisors looking on, I often felt a hollowness in the way we talked about living with risk—as if risk were just a number, rather than something that weaves into the fabric of our lives.

*

What does it mean for my own uncertainty to take center stage as I train to be a genetics provider? Every six months or so, I go in for screenings related to my cancer risk. When the technician calls me, I change into my hospital gown, slip on my rubbery hospital socks, and get hooked up to an IV. I am guided into the MRI suite, IV tube dangling from my arm, and I step into the cold room full of wartime sounds. Face down, breasts out, my body is brought under medical scrutiny. Sometimes I talk about journal articles I’ve read; sometimes I get a smile, as if I’m being cute. More often than not, I am called back for additional testing. The possibility of cancer enters the foreground, and I am plunged into a hundred what ifs: technical, logistical, relational, emotional. I begin looking up surgeons; I think about freezing my eggs; I read the fine print of my health insurance policy.

As a BRCA1 carrier and genetic counselor in training, I am learning that this is, simply, what it is to live in surveillance. We may keep turning our heads this way and that. I spend my days working with risk; I wait for the phone call telling me just how suspicious to be of my own body. So far, the news has been good: today, I don’t have cancer. Meanwhile, I’ll keep slipping the hospital socks on and off my feet, walking forward as best I can along my path through suspicious country.

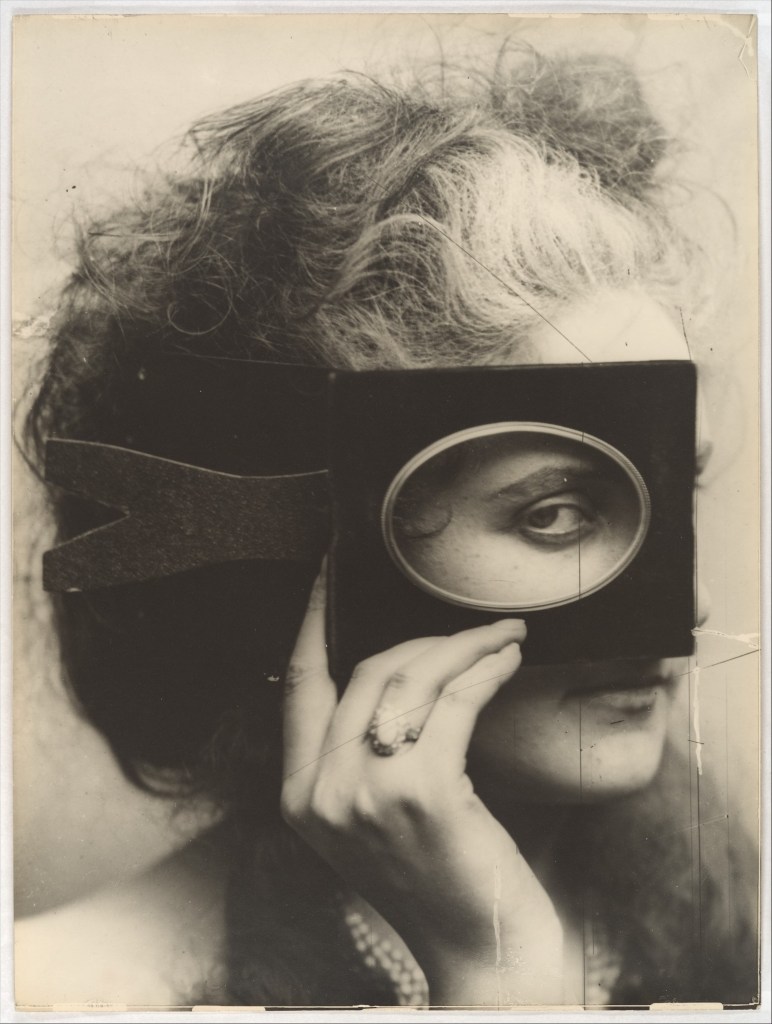

Featured Image: “Scherzo di Follia” by Pierre-Louis Pierson. Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005. Public Domain. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

References

Apraxine, P. (2000). “Scherzo di Follia,” La Divine Comtesse: Photographs of the Countess de Castiglione. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Montaigne, M. de. (1993). Michel de Montaigne: The Complete Essays. Penguin Classics.

Riggs, N. (2018). The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying. Simon & Schuster.