I’ve only seen it a few times. I don’t mean when you pass someone at the grocery store, their head covered in a silk turban, pale skin, no eyebrows. I mean at close range—when it’s beyond repair.

The first time was ten years ago, an older Taiwanese woman brought in by her concerned daughter. In the exam room, alone with this patient, I asked her about changes in her breasts over the last year.

“Have you felt any lumps?” I waited for the translator to explain my question.

She looked at the floor and deliberated. Then addressed the phone attached to the wall. “There is a ball coming out,” the translator replied.

I considered this; my eyes drifted to the paper vest covering her upper half, airy on her thin frame. Her right shoulder hunched forward slightly—I followed its curve to the nook of her armpit where the skin was taught and pink, like an overfilled water balloon.

“Is it okay if I do your exam now?” I asked.

She nodded.

I was a year out of NP school at the time. My white coat still felt more like a stiff costume than a work uniform. I often had the feeling I was reciting lines from an unrehearsed script, especially with older patients. Couldn’t they see through my ruse? When inspecting lymph nodes, I frequently feared missing something (had I ever really felt an axillary lymph node?) but with her, a different fear emerged: I can see her axillary lymph nodes.

Lightly, I lifted her right arm, pressed three fingers in a circular motion under her arm pit. Her skin was hot and shiny. I lightly palpated down her arm, though there was truly no point—I was just buying myself time before I’d have to look under the paper. She rotated her shoulder back to allow my hand to continue its exam and the vest fell open, baring the right side of her chest.

Cancer was no stranger to me; my mother had had it twice, once in each breast before undergoing a bilateral mastectomy. She first got diagnosed when I was a freshman in high school, then again when I was a freshman in college. Pre-menopausal breast cancer is somewhat rare, unless you possess genetic mutations like BRCA-1—the one she’d passed on to me. I tried not to think about this as my eyes focused on the patient before me.

Her right breast was gone, completely eaten away. In its place, a mottled red puddle with a grey, bulbous mass spilled out, a ghostly succulent. How long had she been living like this? Had her daughter seen? I wondered what my face looked like. I tried to maintain a composed expression as I softly pulled her vest closed.

“This looks like cancer,” I said gently.

The pause as the translator told her what she must have already known—you didn’t need a medical degree to understand something was seriously wrong.

“We can refer you to an oncologist for treatment.” I went on, though I imagined things were too far gone. A more appropriate referral would probably be hospice.

She looked at me and spoke a few words. Then the translator’s voice: “I don’t want treatment. I want to allow things to progress naturally.”

In difficult clinical scenarios, it’s helpful when a patient has undressed—this creates an excuse for you to step out and collect yourself while they put their clothes back on. I used this tactic to exit that day, put space between the patient’s tumor and myself, the fact that our medical system had little to offer her. I can’t remember how the visit ended—if she allowed us to speak with her daughter or if she accepted referrals to oncology or palliative care—that’s been erased by the thousands of patient encounters I’ve had since. Mostly, her armpit and absence of breast remain.

She must be deceased by now. I hadn’t thought about her in years until a few weeks ago.

A new patient recalled her to me. I’ll call her Laksanara. She was 29, a recent California transplant, understood more English than she could speak. She’d moved from Bangkok two weeks earlier and came to our health center to discuss her birth control pills and the irregular bleeding with pelvic pain she’d been having the last few months. She’d never had a pap smear.

Laksanara looked like the kind of person I would have been friends with in college—oversized hipster glasses, stick-and-poke tattoos on her forearms, mismatched dangly earrings made from feathers and beads. Her smile was warm and disarming.

“What brought you to California?” I asked, pulling up a stool.

“I come for school,” she replied, not waiting for the translator.

On her initial exam, Laksanara was bleeding so heavily I couldn’t visualize her cervix. I tried to clear away the blood with scopettes—long white sticks with tightly-bound cotton balls at the end (I call them Q-tips for giants)—but I never got a clear look. I thought I might have seen a cyst on top but wasn’t confident. I inserted a pap brush and spatula, obtained a sample from her cervical opening and decided I wasn’t overly concerned. Laksanara said she was on her period and I presumed her irregular bleeding might be due to the low-dose of estrogen in her pills. When I examined her uterus with my hands, her cervix felt firm, but I figured it was most likely a collection of cysts or perhaps even a fibroid in her lower uterine segment—it wasn’t impossible for people in their late-20’s to get these firm, benign tumors.

Laksanara had moderate tenderness when I pressed on her uterus, but her cervix was non-tender. I considered treating her for an infection, but she was well-appearing, no fever or altered vital signs—she could have just been feeling crampy from her period. I decided to test for STIs while doing a complete blood count to check for systemic infection. Maybe Laksanara needed treatment for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)? Either way, I figured testing was the first step in obtaining more information.

The following day, the medical records department contacted me to say Laksanara had an elevated white blood count—did I want to treat for PID?

Yes! Thank you. I messaged back.

A week later Laksanara’s pap result returned “unsatisfactory specimen,” positive for HPV—the very common, but potentially cancer-causing virus.

Laksanara came in the next day for follow-up.

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

She smiled. “Only little pain.” She held up her fingers to show about a centimeter of space between her index finger and thumb. “Still bleeding though.”

I explained that we should repeat her pap test if she felt comfortable doing another pelvic exam. She said sure.

As I inserted the speculum, blood pooled in the lower blade. Opening the instrument to visualize her cervix, blood continued to course slowly towards me. I used a Q-tip for giants to absorb it—then 2, then 3. No matter how much I absorbed or wiped away, there seemed to be an endless slow stream obscuring my view. After over a dozen scopettes, I peered inside and there it was: a mottled puddle of ulceration, two gorged arteries feeding it—then the blood concealed my view again.

How had I missed this?

I felt an ache in the back of my throat, heat surging up my neck to my cheeks—in moments like these, I was grateful for pandemic protocol, the thin, blue surgical mask over my face.

“We’re done with your exam,” I said, wiping blood from the tray between her legs. “I’ll step out for a moment so you can get dressed.”

In the hallway, I inhaled deeply, then exhaled slowly. Through the closed door, I heard the crumpling of exam paper, Laksanara getting up to put her clothes back on.

How advanced is her cancer? I wondered. How much time does she have? Even though the one-week delay in diagnosis would have little bearing on her prognosis, I didn’t want to be complicit in a system that was bound to have more hurdles and delays. With no insurance, minimal English, and ineligibility for state-sponsored health coverage due to her age and immigration status, Laksanara would face even more challenges in obtaining care.

I imagined myself her: excited to be in a new country, learning a different language, starting down a fresh path with varied opportunities—then to suddenly learn I had cervical cancer before my 30th birthday. I imagined the fear I’d feel for my body, my fertility, my future, my life; it wasn’t hard to imagine these things because I’d worried about them many times since learning I was a BRCA-1 carrier. If Laksanara didn’t want things to progress naturally—and I got the feeling she didn’t—we needed to get her into treatment ASAP.

I readjusted the mask on my face and lifted my hand to knock on the door. I prepared to tell her what I’d seen and help her navigate the system however I could—there was no time to waste.

*Names, physical characteristics, and other identifying information have been changed to protect patient privacy.

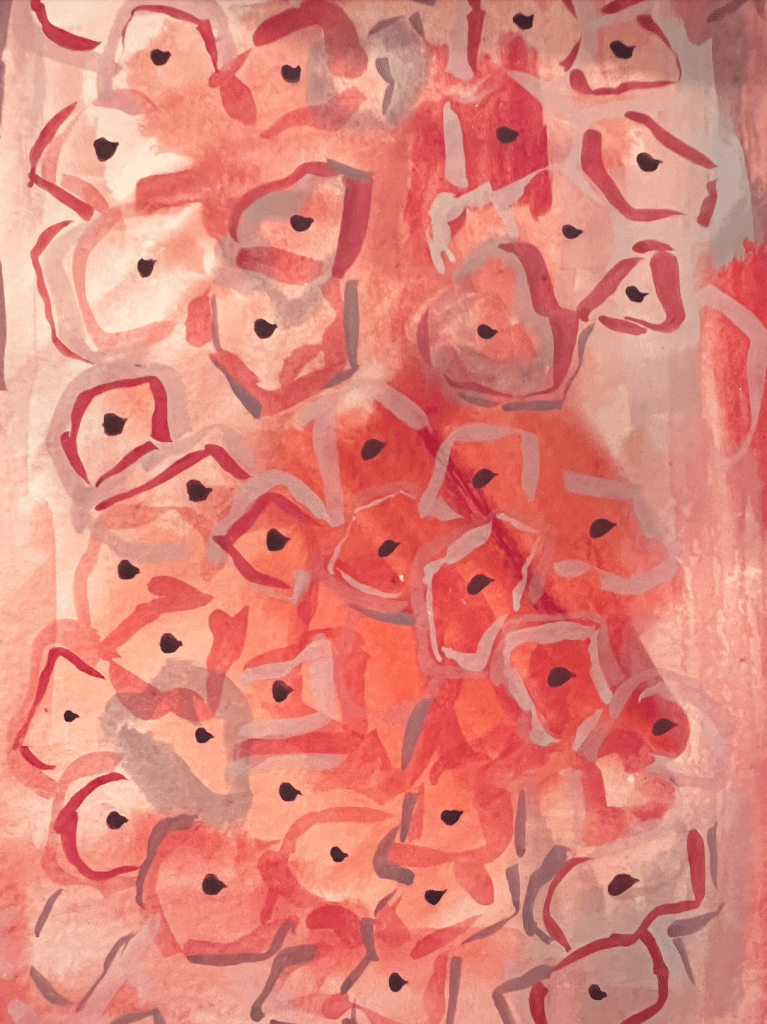

Cover Image: by the author