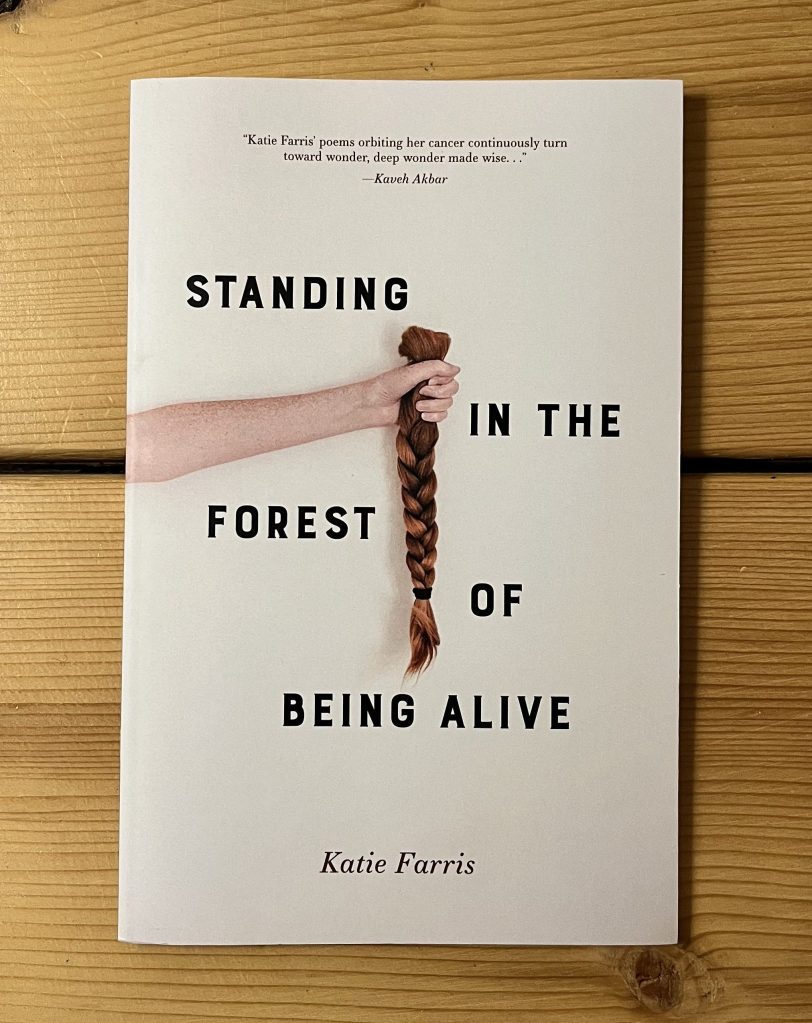

When Katie Farris’s Standing in the Forest of Being Alive was published by Alice James Press last year, I couldn’t put it down—and after I finished reading through it, I didn’t want to put it down. I kept it in my car as I drove to the National Institutes of Health for a bioethics fellowship; I brought it with me in my backpack as I shadowed the palliative care service and put my body through its biannual BRCA1 imaging. Eventually, I placed the book back on the to-be-read stack by my bedside, hoping to keep returning to it. I have.

A memoir in poems, Standing in the Forest of Being Alive chronicles Farris’s experiences of breast cancer care. She writes of many of the hallmark features of oncology: surrendering her hair on the morning of a port surgery; navigating bodily change through surgery; and grappling with mortality—her own and others’—as she faces the shock of a young diagnosis, treatment, and active waiting. Meanwhile, Farris moves between scenes of bodily care and the bodies of poems. A poet, translator, and literary scholar, Farris has written these poems in conversation with other texts, and especially with the work of Emily Dickinson. “Have I said it slant enough?” she asks, of the scene of her cancer diagnosis:

Here’s a shot between

the eyes: Six days before

my thirty-seventh birthday,

a stranger called and said,

You have cancer. Unfortunately.

And then hung up the phone.

While cancer is often described as an individual phenomenon, Farris writes of her cancer care as fundamentally relational. In a poem early in the book, she describes how, in solidarity with her first cycle of chemotherapy, “our cat leaves her whiskers on / the hardwood floor.” Throughout her poems, treatment is depicted as not only affecting the body connected to the IV. One’s partner, one’s cat, and one’s environment, too, are touched by chemotherapy, surgery, and broader bodily change. In a striking poem co-authored with Farris’s pathologist, a pathology report is paired with Farris’s voice: “Dear Doctor—you’ve done my work for me in your first line / with your tidy slanting rhyme of specimen and formalin.” Throughout the text, exchanges between individual bodies link care relations to a poetics of the body.

In writing about the body and its relationships, Farris also invites into the text an erotics of cancer care, asking: what is the relationship between care and desire for the person living with cancer? Farris explores these questions through the frame of her marriage, with its concrete intimacies and “slow / sweet collapse into / oneness.” In “An Unexpected Turn of Events Midway through Chemotherapy,” she writes: “I’d like some sex please. / I’m not too picky— / (after all, have you seen me? / so skinny you could / shiv me with me?)” Her experience in cancer treatment is not merely one of inhabiting the patient role, but rather of enduring oncology in and into a desiring body.

The erotic is, as Audre Lorde wrote, a “source of power and information within our lives” (Lorde 2020). This is especially true in oncology, where the body is read by providers as a system of risks, symptoms, and side effects. Further, in and beyond cancer care, normative social forces often work to police sensuality; “cancer works very hard to make life unsexy,” a Modern Love columnist writes (Glaser 2006). A striking example: Lauren Mahon, a health activist and breast cancer survivor in the U.K., has devoted her career to helping cancer survivors feel more connected to their bodies after treatment. Her organization, GirlsVsCancer, aims to raise awareness of sexual health after cancer. Last month, Mahon ran a billboard campaign across London, triumphantly proclaiming: “Cancer Won’t Be the Last Thing That F*cks Me.” Shortly after the billboards went up, though, they came down. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), a major U.K. advertising regulatory agency, deemed them too likely to cause “widespread offense.”

If cancer works very hard to make life unsexy, Farris’s writing is, in her own words, “a prophylactic against [this] loss.” Like Mahon’s billboards, Farris labors to express the vitality and sensuality of the body living through cancer treatment. Of course, poetry does work that a billboard cannot. The poetry of Standing in the Forest of Being Alive speaks to erotics, yes; but it also speaks to grief; to the brokenness of the U.S. healthcare system; to the taste of a pebble in one’s mouth; to caring for a lover’s belly, “how it rounds itself: my hemisphere.” In her poems, Farris utters a mighty invocation of the body as a sensuous entity—in relation to other bodies—bodying forth with language.

As I return to Standing in the Forest of Being Alive, I am struck by the abundance of feeling that spans these poems. Cancer may be a “total social fact,” as anthropologist Lochlann Jain has written (Jain 2013). But what does it feel like to endure a total social fact, and how does one render that feeling in poetry? Farris answers: “One must train oneself to find, in the midst of hell, / what isn’t hell.”

References

Farris, Katie. 2023. Standing in the Forest of Being Alive. Alice James Books.

Glaser, Jennifer. 2006. “Mortality Can Be a Powerful Aphrodesiac.” The New York Times, August 13.

Jain, Lochlann. 2013. Malignant: How Cancer Becomes Us. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lavinia, Emilie. 2023. “‘Self-Touch Saved My Life and Now I’m Helping Women with Cancer Enjoy Sex.’” Cosmopolitan, November.

Lorde, Audre. 2020. “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” in The selected works of Audre Lorde, edited by R. Gay. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Taylor, Nick Paul. 2024. “Sweary Cancer Charity Billboard Banned for Causing Offense in the UK.” Fierce Pharma, January.

Ward, Caleb. 2023. “Audre Lorde’s Erotic as Epistemic and Political Practice.” Hypatia 1–22.