A crowded family photo (cover image). Rather a strange one though. People are nowhere to be seen as men replaced by specimen and each are clothed in jars.[1] The photo comes from a medical album that documents the surgical achievements in Haseki Nisa Hastanesi [Haseki Women’s Hospital] in Istanbul during the 1890s. The jars contain the tumors removed from women’s wombs after hysterectomy. Not only the tumors themselves but the women are also the subjects of the album[2], which oscillates between a clinical report and portrait photography. Although the use of photographic document at the time is not rare, and even increasingly popular among medical circles both in the Ottoman Empire and Europe, it is still peculiar to create an archival document in such an in-between position that clinical evidence of health is imbricated in the common practice of studio portraits, both of which foregrounds the body for diverse reasons.

These photographs capture women with their stitched cuts next to jars containing the tumors recently removed from their bodies in a domestic environment – an impression created by studio props and backgrounds. The body’s corporeality and vulnerability are foregrounded in this staging. This exposition reminds us that the body is both open to threats (uterus cancer) and likely to be a threat itself (being reproductive no more). In that regard, photography is very telling about how to read a medicalized body, or to medicalized it in the first place.[3]

The photographs reveal a violent regime of seeing, since the choice of subject and the positionality of the women hint at a forced visibility for a particular readability of history. We don’t know if these women volunteered to pose after surgery—probably not—or, whether they are comfortable with such situatedness—again, probably not. Yet, the photographic medium itself suggests that this realm of probabilities is generative. It allows us not to reduce what we see into a simple context and probe otherwise.

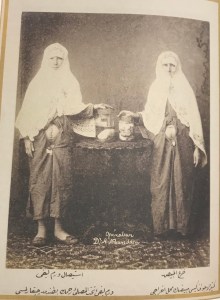

I only bring a few photographs here taken from the exhibition catalogue, Camera Ottomana. And rather than historicizing them further[4], I want to entertain a short close reading of gestures and stitches here.

Close-Up

fig.1

Each woman directly looks at the camera; either with a half-hidden smile (the woman on the left in fig.1), out of sheer acceptance of duty (fig.2) or with a reserved disdain (fig.3). Although interpretations can vary, the hybrid form of the photographs, the fact that these are post-surgery studio portraits, resists the complete objectification of its subjects by scientific and male gazes. The centrality of the body is congruent with the axis of the cut. This can be read as the dissonance/resonance between private and public, interior and exterior as the photographs suture bodies and distinct spaces. The visibility of the stitches evokes a spatial polyphony.

fig.2

The women’s hands are slightly folded, perhaps as a sign of discomfort or a glimpse of their readiness to pose according to the guidance of the photographer. Nevertheless, these women are aware of their to-be-looked-at-ness, the violated intimacy of their position. And hence, they also hold the power to respond, which might explain the variety of gazes. The way they approach or hold on to the jars raises the question of property—the property of the excess to be precise. Here, the ownership seems asymmetrically distributed between the women (tumor as a sign of recovery), the state (tumor as a sign of power) and the photographic medium (tumor as a prop). Vertical stripes in their simple and identical hospital gowns accompany the verticality of their scars. This pairing somehow smooths our encounter with the operated bodies. As if, the collaborators of this very event, the surgeon Ahmed Nureddin and the photographer Nikolas Andriomenos, aimed the cut dissolving into the setting, and the act of photography seeming almost natural. Still, in such a domesticized and neat setting—a neatness to match the sterile conditions of the operating room perhaps—the whole scene seems an excess itself. Another excess is observed in the distribution of gazes. The women directly look at the camera, supposedly at the viewer, yet, the viewer’s sight is divided between the jars, stitches, and the body.

fig.3

The word stitch comes from proto-Germanic stilkiz; also the source of German stich, which means “a pricking, prick, sting, stab” as a noun and “to stab, pierce” as a verb. Quite poignantly, it becomes the punctum of these photographs à la Roland Barthes, that goes beyond what is documented and pierces us to engage with what we see in a different way. We are unsettled in such a way that the photographs reveal their narrative fractures. Personal stories hinted at the captures (type of tumor, information on patients) leak into the story of scientific success and medical discourse of power in their inaccessibility. Photographic medium becomes an apparatus of hi(story) and bodily production that entangles not only the women who are photographed and the photographer and the surgeon, but also the discourse of medicine and health. The photographs suture the personal, medical, scientific, and political. They uncover that the body is a layered and porous entity as its relations are not seamless or a consequence of a certain intention or a discourse merely.

Cover Image: from Zeynep Çelik’s “Photographing Ottoman Modernity.”

Bibliogprahy:

Çelik, Zeynep. “Photographing Ottoman Modernity.” Photo-Objects : On the Materiality of Photographs and Photo Archives, Julia Bärnighausen, Costanza Caraffa, Stefanie Klamm, Franka Schneider, and Petra Wodtke (eds.), 2019.

https://www.mprl-series.mpg.de/media/studies/12/9/studies12chap08.pdf

Çelik, Zeynep and Edhem Eldem, eds. (2015). Camera Ottomana: Photography and Modernity in the Ottoman Empire. 1840–1914. Istanbul: Koç University Press.

Gürsel, Zeynep Devrim. “A Picture of Health: The Search for a Genre to Visualize Care in Late Ottoman Istanbul.” Grey Room 72, Summer 2018, 36–67.

https://doi.org/10.1162/grey_a_00248

[1] ‘The caption identifies the contents of each jar: most are fibroid tumors (verem-i lif) of the uterus, the exceptions being a tumor resulting from cancer of the cervix in the first jar on the right and two bladder stones, weighing 40 and 17 dirhems (129 and 54.4 grams), respectively, in the first jar on the left.’ Zeynep Çelik, ‘Photographing the Ottoman Modernity’.

[2] The album in question exists in two collection, Abdülhamid II’s Yıldız Palace Collection and Ömer Koç’s Collection, with some differences regarding personal information and the number of photos. (See Gürsel).

[3] Photographs were not taken for a wide-circulation, however, they were the proof of the medical and technological advancements in the Ottoman state and the confidence of the clinical eye.

[4] For a detailed reading about the hospital’s history see: Zeynep Çelik, “Photographing Ottoman Modernity” and an extensive reading of the album see: Zeynep Gürsel, “A Picture of Health: The Search for a Genre to Visualize Care in Late Ottoman Istanbul.”