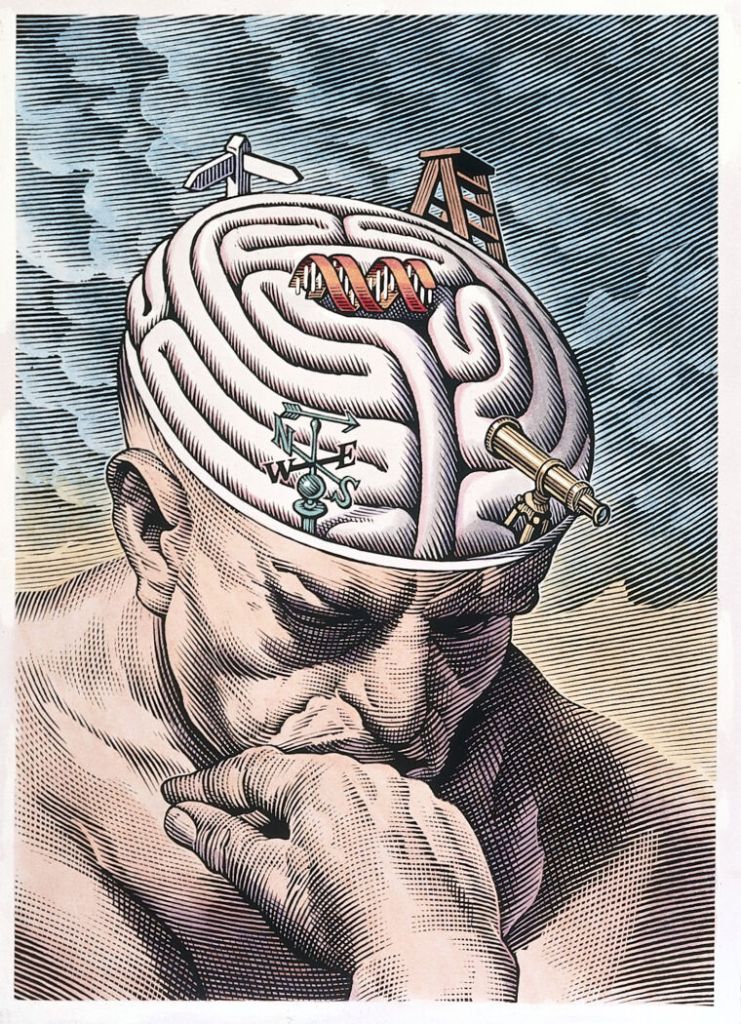

Image Credit: Sanderson, Bill. “The gyri of the thinker’s brain as a maze of choices in biomedical ethics.” Scraperboard drawing, 1997. Wellcome Collection. [Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)]

Therapy or Enhancement? Bioethics in Transhumanist Science Fictional Interpretations of the Body

Since the Enlightenment, the idea of perpetual progress and the hegemony of rationality have shaped the Western conception of the ‘Human subject’ in (neo)liberal, anthropocentric terms. The twenty-first century, however, has seen a paradigm shift brought about by what Klaus Schwab categorises as the “fourth industrial revolution”—a time marked by enormous leaps in the development of robotics, artificial intelligence, neurosciences, information technology and biotechnology, among others, as well as by the philosophical ramifications of their emergence (Baelo-Allué & Calvo Pascual 4).

As these technologies develop, categories previously used to define and thus distinguish the human from the nonhuman are becoming increasingly obsolete. We may look at organic/synthetic assemblages like prosthetic-clad amputees, for instance, examples that destabilise these definitions and the Cartesian hierarchies they are founded upon: those of mind over body, and human over animal and technology. As a genre that largely extrapolates the possibilities of the human species in the future, science fiction has long speculated on how these rapid techno-scientific advancements may change the way in which we see ourselves and interact with the world. The topic of human enhancement, in particular, has always been prevalent within the genre. Not only has science fiction explored the “mythic aspirations that drive the desire to improve the human condition via science” and the ways in which these advancements may shape societies, but it has also been an appropriate medium through which to ponder the underlying bioethical anxieties (Schick 162).

No longer limited to the science fictional realm, contemporary research seems to bring these dreams closer to reality. Silicon Valley is currently home to pioneering projects that seek to target the cause of certain illnesses at their core, rather than focus on rehabilitating, hindering further damage or simply managing symptoms. To name a recent example, Preventive is a start-up supported by billionaires Brian Armstrong and Sam Altman that aims to eradicate hereditary diseases from their root through embryonic gene editing (Harrington). Such proposals refer to the concept of “designer babies,” which has long been part of public debate and spectacle, particularly since biophysicist He Jiankui’s infamous creation of the world’s (allegedly) first genetically edited human babies, back in 2018 (Stein). His posterior incarceration and public condemnation seem to point to the controversial nature (and illegality) of the experimentation, but the idea still overlaps with widely accepted medical practices. These include prenatal screenings and diagnoses for genetic disorders like down syndrome, as well as the rise of velvet eugenics, as discussed in a past article by Perkins and Gulledge on this same journal.

Being a science fiction scholar, my concern with such endeavours relates to how easily permeable they are to transhumanist discourses that, more often than not, lack a critical understanding of why the bodies, and embodiment, matter. As stated in the Transhumanist Manifesto written at the beginning of the millennium, this philosophical current advocates for the improvement of health and the elimination of pain and death by means of technology and science. It sees homo sapiens, as we are and live in our current world, simply as a point in an evolutionary progress where a “correct” implementation of science and technology will overcome the human body’s biological and cognitive limitations (More 4). Some theorists suggest that we, right now, may to an extent be considered ‘transhuman,’ due to our use of technological devices such as hearing aids, prosthetic limbs or pacemakers (Filip 67). The ‘posthuman’ itself, however, would be the goal at the end of this linear progress: the furthest evolutionary state of the species, an enhanced version of the current human.

But, where do we draw the line between what is therapy, i.e., the mere treatment of symptoms to improve quality of life, and what is enhancement, which is culturally deemed to connote an individualistic desire for self-improvement (Filip 70)? And how do we deal with the bioethical dilemmas that they pose for human identity? As Sanderson’s scraperboard above illustrates, this bioethical debate encompasses many things, since the difference between both depends on sociocultural factors that deem one trait or another more valuable.

Among transhumanist principles, we find the recurrent idea of “perpetual progress,” humans’ right for “self-transformation,” a “practical optimism” by which humans are free to actively strive towards and try and shape their own desired future, the prevalence of “rational thinking” and an individual need for “self-direction” (More 10). I would like to reflect on the second one, the idea of “morphological freedom” by which one exercises their right to do what they want with their body, since it brings forth the issue of ownership. This view perceives the body as a (disposable) commodity in need of actualisation when, in truth, it is the very core of experience, as our sensory and cognitive apparatuses shape how we perceive and experience life. It goes without saying that these principles relate to eugenicist discourses that have been prevalent, in one way or another, since Francis Galton’s during the nineteenth century.

Transhumanist acceptations of this ideal posthuman model thus deliberately omit the multiplicity of bodies that already exist, many of which rely on technological prostheses on a daily basis. Kathryn Allan, for instance, has conducted significant research on science fictional portrayals of this posthuman from the perspective of Disability Studies. She notes how the disabled body seems to be completely erased from such visions of the future, as it does not seem to qualify as a “quality human being,” to borrow Sieber’s terminology. This is done by having physical and cognitive difference be perceived as monstrous, or by conforming divergence to the norm through rehabilitation, sometimes relying on the figure of the “supercrip” to do so, that is, disabled characters who are granted almost magical or superhuman powers precisely because of their impairment. Hence, “by construing the ‘abnormal’ body as disabled and in need of medical intervention, cure, or rehabilitation in order to make it ‘normal,’ we elide the fact that human bodies exist along a spectrum of variation and ability” (Allan 2).

As a matter of fact, an analysis of the discursive devices used by transhumanists in educational TED Talks on the benefits of human enhancement shows further proof of its link to science fiction and disability. Filip’s research illustrates that imagery of conquest underlies the view of humans’ physical and cognitive abilities as limitations to be overcome, further emphasising the bias denounced by Allan (70). Filip notes that the “narrative of human enhancement is . . . framed as a human conquering and exploring of the vast and cosmic universe” (73), in an array of science fictional symbolisms that reify the body and endorse the Cartesian mind/body hierarchy. To my eyes, this is inherently problematic, as it presents the body as a barren land devoid of any worth, disregarding the importance of embodiment for the lived experience of people with disabilities.

Going back to current examples of multibillionaires’ dreams of self-aggrandisement through technological prostheses and life extension, we may find examples of this, for instance, in Elon Musk’s Neuralink project. Their Brain-Computer interface neural implants, as stated on the official website, aim to create a generalised brain interface that “will restore autonomy to those with unmet medical needs today and unlock new dimensions of human potential” (“Neuralink”). Such a phrasing indeed frames technology as tool, as prosthesis, as a type of therapy aimed to benefit those with different impairments—in this case, trial tests have already been conducted on patients with spinal cord injuries. However, the claim is immediately followed by the promise of a yet untapped future potential for the human species as a whole, a nod to the enhancement and betterment of human capabilities.

The answer to all these questions, for me, lies in the understanding of the human body (and human identity) defended by the current of posthumanism. By acknowledging the phenomenological and existential importance of embodiment—saying “I am my body” or “I am a being, in my body” instead of “I have a body” acknowledges the “many processes, experiences, and relations that are dynamically co-constituting ‘my body'” (Ferrando 131). Based on interspecies compassion, an understanding of identity in terms of multiplicity and permeability, and emphasising horizontal rather than vertical relations, posthumanism seems to me a more appropriate approach to elucidate the contemporary bioethical debates that surround the discourse on human enhancement.

Works Cited

Allan, Kathryn. “Disability in Science Fiction.” SF 101: A Guide to Teaching and Studying Science Fiction, edited by Ritch Calvin, Doug Davis, Karen Hellekson, and Craig Jacobsen, Science Fiction Research Association, 2014.

Baelo-Allué, Sonia, and Mónica Calvo-Pascual. “(Trans/Post)Humanity and Representation in the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the Anthropocene: An Introduction.” Transhumanism and Posthumanism in Twenty-First Century Narrative, Routledge, 2021, pp. 1-20.

Ferrando, Francesca. Philosophical Posthumanism. Bloomsbury, 2019.

Filip, Loredana. “Vigilance to Wonder: Human Enhancement in TED Talks”. Transhumanism and Posthumanism in Twenty-First Century Narrative, edited by Sonia Baelo-Allué and Mónica Calvo-Pascual, Routledge, 2021, pp. 65-78.

Harrington, Lucas. “Announcing Preventive.” Preventive, 30 Oct. 2025, https://www.preventive.bio/blog/announcing-preventive.

More, Max. “The Philosophy of Transhumanism.” The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future. Edited by Max More, and Natasha Vita-More. Wiley-Blackwell, 2013, pp. 3-17.

“Neuralink: Pioneering Brain Computer Interfaces.” Neuralink, https://neuralink.com/. Accessed 8 Nov. 2025.

Perkins, Jo, and John Gulledge. “Rethinking ‘Survival of the Fittest’ through Bird Box.” Synapsis: A Health Humanities Journal, 18 Jul. 2024, https://medicalhealthhumanities.com/2024/07/18/rethinking-survival-of-the-fittest-with-bird-box/.

Schick, Ari. “Science Fiction and Bioethics”. The Edinburgh Companion to Science Fiction and the Medical Humanities, edited by Gavin Miller, Anna McFarlane and Donna McCormack, Edinburgh University Press, 2025, pp. 155-169. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474485081-015.

Stein, Rob. “Chinese Scientist Says He’s Created First Genetically Modified Babies.” NPR, 26 Nov. 2018, https://www.npr.org/2018/11/26/670991254/chinese-scientist-says-hes-created-first-genetically-modified-babies.