Transformed Food and Dietary Style in Modern Japan

Food redefined

In 1870, Victorian educator Ellis A. Davidson published Our Food: A Useful Book for Boys and Girls in London. In it, Davidson introduced why humans need food and how humans are nourished by it. While detailing the nutritional composition and functions of different foods, he expected to “give some elementary lessons on the proper uses and combination of the different kinds of food” that would help “regulate daily meals” and build “the health of a household” in Britain (Davidson, vii-viii).

Meanwhile on the other side of the Atlantic, American hygienist Edward Hitchcock Jr. published the second edition of Elementary Anatomy and Physiology for Colleges, Academies, and other Schools in conjunction with his father. Like Davidson, Hitchcock Jr. discussed the chemical composition of foods and suggested a set of rules of eating. He recommended that people should consume “one-third food of animal origins” and “two-thirds food of vegetable origins” by weight and use condiment and spices sparingly (Edward Hitchcock Jr. and Sr., 177-80, 183-6). Emphasizing the significance of nutrition to the growth and maintenance of human bodies, Hitchcock Jr. hoped to equip the American public with scientific knowledge of nutrition and habits of healthy eating.

Outstanding educators in their own countries, Davidson and Hitchcock Jr. demonstrated to many people the importance of food to people’s bodily health. Yet they informed more people than they might have expected. In 1872, with reference to Hitchcock Jr.’s writings and the works of other prominent hygienists in the United States and Britain, Japanese physician Toki Yorinori (土岐頼徳) complied the first health-cultivation (yōjō, 養生) textbook for elementary school in modern Japan. In his textbook, Primer on Health Cultivation (Keimō yōjō kun, 啓蒙養生訓), Toki introduced food as a complex chemical composition of “carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen,” the necessary elements to form all animal bodies (12). He pointed out that “beef, eggs and milk” contained all four elements and thus were “the best nourishing food” for human bodies (Toki, 12). In 1875, translator and educator Yamamoto Yoshitoshi (山本義俊) translated Davidson’s Our Food into the first systemic monograph on the science of food in the country. Titled New Book on Dietary Regimen (Inshoku yōjō shinsho, 飲食養生新書), the book introduced that “nutritious food” consisted of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen; that “heat-giving food” did not contain proteins; that these chemical compounds in food were digested, absorbed into blood, and transported to every part of the body to form muscles and nerves; and that people needed to eat the proper amount of food to keep warm and regenerate their bodily tissues (Yamamoto, 35-7).

Departing from the tradition established by food materia medicas in the pre-modern period, these new books on food exposed Japanese readers to a fundamentally different depiction of their daily intake. No longer referring to Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao gangmu, 本草綱目) or theories of Chinese medicine that describe foods as being cold or hot, they conceptualized foods in accord with chemistry, anatomy and physiology. Narrated in a new language of chemistry and quantification, food was transformed into a chemical compound of measurable nutrients. The following comparison of descriptions of wheat in Food in Our Country (Honchō shokkan, 本朝食鑑) and A Summary on Diet (Inshoku yōron, 飲食要論) showcases the changes straightforwardly:

Honchō shokkan (published in 1697): Wheat has a sweet flavor. It is slightly cold with no poison (newly harvested wheat is hot in nature; old wheat is mild). Wheat can relieve restlessness, quench thirsty, arrest sweating, bleeding and secretion, and nourish the heart. Compendium of Materia Medica records that according to multiple scholars, immature wheat grains are salty and cold; wheat flours are cool; cooked wheaten food is warm…(31-2)

Inshoku yōron (published in 1874): Food of vegetarian origins are most valuable and important. Grains belong to this genre of widely used food. Being particularly rich in nutrients and fast to be digested, wheat is a matchless grain. Apart from milk, wheat is perhaps better than any other food at maintaining people’s physical strength. It contains 10 to 15 percent of gluten, 60 to 70 percent of starch, some valuable alkali and phosphorus salts, a small amount of fat, and even less water that amounts 12 percent in average. It consists of a solid body, with most starch inside grain and gluten, fat, and minerals on the husk… (7-8)

The spread of new knowledge regarding food led to dramatic changes in Japanese people’s understanding of food as well as dietary life. People began to pay attention to nutritional composition and the digestive process of food, which reshaped measures of food quality. Good food was then seen as needing to contain more nutrients and be easily digestible, whereas bad food was seen as lacking nourishing substances and burdening digestive organs. People began to particularly value nitrogenous compounds (also introduced as protein in some books). They often ranked protein-rich beast meat, milk, and egg atop of all foods, followed by bird meat, fish, shrimp and crabs, shellfish, grains, beans, vegetables, and fruits.

A series of Yomiuri Newspaper articles in 1874 and 1875 showcased such changes well. Titled “About Health Cultivation,” the articles introduced to the public a new hierarchy of foods:

Meat of beasts and birds was the best. People eating meat expelled smaller feces and less urine, which proved that meat can be well digested. It was rich in nutrients that human body absorbs to form blood and flesh. British soldiers ate more meat than soldiers in other western countries. Thus, they complained less of lassitude (Yomiuri Shinbun, December 4, 1874, 2)

Fish was regarded as premier food in Japan for long. However, it was in fact not as nutritious and digestible as meat. Shellfish was even worse, with oysters being the only exception (Yomiuri Shinbun, December 4, 1874, 2).

Among grains, rice helped produce bodily fat and regenerate blood; yet it had much dross and limited nutritive substances. Therefore, people who ate lots of grains were big in size but physically weak and lethargic (Yomiuri Shinbun, December 4, 1874, 2).

Some vegetables were difficult to be digested. Gourds and pickled daikon radish were among these and could not nurture human bodies. Carrots and potatoes were the opposite. Miso sauce was labelled as rotten and badly digestible. It was suggested that “people who had miso soup three times a day should reduce it to twice; and those who had two bowls should only have one now”((Yomiuri Shinbun, February 19, 1875, 2).

Changing Dietary Style

Spreading belief in the nourishing power of meat and milk products altered the dietary habits of many Japanese people, elites and commoners alike. In the summer of 1870, Fukuzawa Yukichi (福沢諭吉) drank milk while fighting deadly typhoid fever (Keio University, 100-101). After his recovery, Fukuzawa prized milk as a life-saving nourishment that helped him “nurture and restore vigor” (Keio University, 101). To inform more people of milk’s health benefits, he wrote an advertising essay On Eating Meat (Nikushoku no setsu, 肉食の説) for the milk seller Tsukiji Gyūba Company. The imperial family adopted the “healthier” habits of eating meat and drinking milk. In November 1871, Emperor Meiji began to drink milk twice a day and mixed it with coffee. Recommended by court lady Hirohashi Sadako (広橋静子) and the chief minister of the imperial household Tokudaiji Sanetsune (徳大寺実則), Empress Haruko also began to have “nutritious milk” (Kunaicho, 604-5). The royal kitchen started serving beef and lamb no later than December, 1871, and sometimes offered pork, venison, rabbit meat and boar (Kunaicho, 607).

Outside of the imperial palace, commoners started to develop a taste for such nourishments too. Contemporary popular literature captured the phenomenon. In the novel The Beef Eaters (Aguranabe: ushi-ya zōdan, 安愚楽鍋: 牛屋雑談), Nozaki Bunzō (野崎文蔵) vividly described how milk, cheese, and butter were sold as medicine near Sensō Temple (浅草寺). Banners of beef pot (ushi-nabe, 牛鍋) restaurants waved high in the sky, attracting eager meat eaters on the street heading toward the Temple (Kanakagi, 5-6). In Tokyo’s New Prosperity (Tokyo shin hanjō ki, 東京新繫昌記), Hattori Seiichi (服部誠一) introduced beef as “the drug store of enlightenment” (kaika no yakuho, 開化の薬舗) and the “good medicine of civilization” (bunmei no ryōzai, 文明の良剤) (Hattori, 31) At countless beef pot restaurants in downtown Tokyo, people dipped sliced beef into pots with braziers and happily enjoyed meaty cuisines with rice and alcohol.

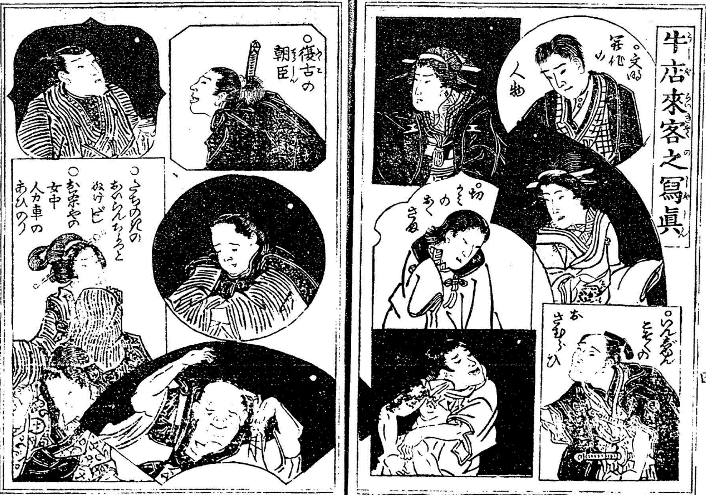

Beef pot restaurant customers

From the mid-1870s, advertisements for milk and meat products appeared frequently on daily newspapers in big cities like Tokyo and Osaka. Often published on the same page with advertisements for medicines, they labelled milk and meat products as healthy delicacies. In 1876, customers could buy 180 ml of nourishing “fresh milk from U.S.-exported cows” in the Akasaka (赤坂) area for 4 sen (Yomiuri Shimbun, June 1, 1876, 4). From butcher Nakagawa (中川) in the Shiba (芝) area, one could buy “health-cultivating beef” (go yōjō gyūniku, 御養生牛肉) which was delicious and so soft “that even people with weak teeth could enjoy” (Yomiuri Shimbun, March 30, 1879, 4). To better utilize animal meat for health purpose, they developed “life-nourishing beef alcohol” (meiyō gyūniku shu, 命養牛肉酒), chicken gelei (keiniku kerei, 鶏肉ケレー), chicken gelei alcohol (keiniku kerei shu, 鶏肉ケレー酒), beef gelei (gyūniku kerei, 牛肉ケレー) and beef extract (gyūniku ekisu, 牛肉エキス). According to the advertisements, women could assure easy delivery of robust babies by eating chicken gelei (Dutch for jelly). One could eat beef gelei to nurture his or her vigor (Yomiuri Shimbun, January 27, 1881, 4). By adding egg into soup made from beef extract, people could cure their lethargy.

Advertisements for chicken gelei and beef extract (1876 and 1882)

Outside of big cities, meat and milk products also grew popular. In Hachiōji area of Bushū (武州八王子), people learned the health benefits of beef and flocked to beef butcher shops. The business of selling beef prospered even more than that in Tokyo. Sugimoto Etsuko (杉本鉞子), the first Japanese best-selling author in the United States, recalled her first taste of meat in Nagaoka of Niigata (新潟長岡). Following the advice of physicians studying western medicine, her father ordered the household to eat “ox flesh” that would “bring strength to his weak body” and “make the children robust and clever like the people of the Western Sea” (Sugimoto, 26-7). She then had beef in soup for dinner at home. Her neighbor Mr. Toda, once a proud samurai, started a new business as a local dairy man and butcher. His business became quite successful, as people’s “faith in meat as a strengthening food gained ground” and more families started to have it on their dining tables (Sugimoto, 28-9).

The “Enlightened” Way of Eating

In the 1870s, the changing dietary style in Japan signified increasing health and nutritional consciousness in a rapidly modernizing society. Ideas associating individual health with national destiny and the collective level of civilization emerged and spread. Like in continental Europe and the United States, the Meiji government and consciousness-raising intellectuals encouraged the Japanese people’s adoption of healthy practices so that Japan could achieve the goals of “increas[ing] production and promot[ing] industry” (Shokusan kōgyō, 殖産興業), achieving a “rich nation and strong military” (Fukoku kyōhei富国強兵), and bringing about “civilization and enlightenment” (Bunmei kaika, 文明開化) (Burns, 17-8; Oku, 167-71).

Japanese “enlightened minds” believed that eating good food would lead the society to enlightenment. As exemplified by educator Yamamoto, “good food” like meat nurtured a healthy and intelligent American population who made the “fast and unrivalled enlightenment” of the country possible. In contrast, people in India ate “bad food” and therefore were not enlightened (Yamamoto, 1). He lamented the lack of nutritional knowledge in Japan and warned that failure to know how to eat wisely would be “a loss for everyone” (Yamamoto, 2-3). When speaking at the opening of a western restaurant, Fukuzawa Yukichi satirized the “children of Edo” (Edokko, 江戸子) with preference for “bamboo shoots in October” or “first eggplants in February” (Keio University, 791). He argued that “a small piece of beef had more nutrients than six kilograms of taro; one cup of milk contained more nutrients than ten daikon radishes” (Keio University, 791). Nevertheless, these people would still chose taro over beef and radish over milk. He called them dispensable “fools and sick men” with faces “as green as vegetable leaves” and brains “as empty as taro’s hollow stems” (Keio University, 292). The consumption of nutritious food like beef and milk gradually became the new more of the “enlightened” community in Japan; those who refused such foods were criticized as uncultured laggards. In newspapers, people who refused to feed milk to their sick children were publicly mocked as stubborn fools (Yomiuri Shimbun, April 12, 1876, 3).

From the mid-1870s, in order to help achieve better health outcomes for the entire Japanese nation, “enlightened” citizens started to gift meat and milk to the poor and sick, even to prisoners with limited access to such nourishments. According to the Yomiuri Newspaper, in early 1876 two Tokyo citizens named Noguchi Yoshitaka (野口義孝) and Noda Eijirō (野田栄次郎) donated 160 kg of beef to the poor in the Tokyo asylum (Yōiku-in, 養育院) in Ueno. Noguchi also donated milk to the asylum residents (Yomiuri Shimbun, February 2, 1876, 1). In Sendai in northeast Japan, an Inasaku (稲作) family donated milk to poor patients in the neighborhood’s public hospital every day from March to October (Yomiuri Shimbun, October 18, 1876, 1). In 1877, Miyagawa Seikichi (宮川清吉), head of the “beef association” (gyūniku kessha, 牛肉結社) donated 120 kg of beef to Tokyo asylum residents (Yomiuri Shimbun, February 12, 1877, 2). In that same month, a person named Minami Uhachi (南宇八) endowed 120 prisoners in the Imperial Japanese Army Prison with 0.3 kg of beef per person (Yomiuri Shimbun, February 21, 1877, 3). Two months later, another two Tokyo citizens named Nasu Chūbei (那須忠兵衛) and Washio Sukegorō (鷲尾助五郎) presented 93 kg of beef to the Tokyo asylum (Yomiuri Shimbun, April 30, 1877, 2).

From 1877 to 1879, a deadly cholera outbreak spread nationwide in Japan. When recommending preventive daily routines for the Japanese people, doctors and public health officials reaffirmed the primacy of animal meat in the food rankings. On August 24, 1877, the Sanitary Bureau of the Ministry of Home Affairs (Naimusho eisei kyoku, 内務省衛生局) published its 5th report on cholera prevention. It suggested that to avoid exposure to cholera, people should eat nutritious and easily digestible food to avert diarrhea and other digestive illness. Thus, the optimal choices were fresh beef, grains, lamb, and chicken (Yamaguchi, 2). Duck meat and pork contained too much fat and were not ideal. Seafood should be forbidden in theory, yet, in reality, a ban on seafood in seaside areas was difficult. The report therefore urged people to choose fresh seafood and cook it well. People were also advised to avoid eating unripe fruits or vegetables, for it would cause digestive disorders (Yamaguchi, 2-3; Uratani, 1-2; Kudō, 2-3).

Synthesis

In 1870s’ Japan, the introduction of the new language of chemistry and quantification in discussions of food reshaped people’s perception of their daily nutrient intake and bodily health. Importation of new nutritional knowledge gave rise to social admiration for so-called western dietary habits like drinking milk and eating meat, as well as laments about traditional meat-light, vegetable-heavy Japanese diets. Popularity of previously uncommon and ‘filthy’ foods like milk and beef surpassed that of premier dainties like abalone and homely cuisines like miso soup. Along with such dramatic changes in Japanese dietary life, the everlasting discussion of food and health as well as the search for scientifically-proven healthier dietary styles also began in Japan at this time. As in other modern states, the goal was not only the nurture of healthy individuals, but also that of a robust nation.

Images:

Featured Image: Gyuten (store selling milk, cheese, butter and other dairy products). Illustration in Robun Kanakagi, Akuranabe: ushi-ya zōdan [The Beef Eaters] Vol. 2. Seishido, 1871, 3-4.

In-text:

Beef pot restaurant customers. Illustration in Robun Kanakagi, Akuranabe: ushi-ya zōdan [The Beef Eaters] Vol. 2. Seishido, 1871, 5.

Advertisements for chicken gelei and beef extract, in “Keiniku kerei,” Yomiuri Shimbun, September 15, 1876, separate print, 4. “Honten fukui gyūosuke, shiten fukui kinsui-dō, gyūniku tsukudani,” Asahi Shimbun, September 8, 1882, Osaka morning edition, 4.

Notes

- Nozaki, better known by his pen name Kanakagi Robun (仮名垣 魯文) was one of the leading writers of gesaku in early Meiji period. Gesaku represents a genre of literary works of playful or joking nature. Gesaku writers usually used simple language to attract as many readers as possible.

- In Tokyo’s New Prosperity, Hattori also introduced beef butcher’s shop and different kinds of beef pot cuisines: “there are three kinds of butcher’s shops. Those flying their banner at the top of the building offer the best beef. Those hang lanterns under the eaves sell beef of medium quality. Those using windows as signboard have beef of lowest quality. All shops show signs with the word “beef” in red color. There are two kinds of beef hot pots. Those boiled with green onions are nami-nabe priced at 3 sen and a half. Those cooked with grease are called yaki-nabe priced at 5 sen.” Here “nami-nabe” means regular pot; “yaki-nabe” means grill pot. Despite the difference in their names, both cuisines are possibly equivalent to sukiyaki, a Japanese dish that consists of slowly cooked or simmered meat and vegetables in a shallow iron pot.

- Bushū, also known as Musashi no kuni, was the largest province in Kanto area of medieval and early modern Japan. Hachiōji area in Bushū was in the west of Tokyo till early twentieth century and is currently part of the Tokyo Metropolis.

- In Japanese, people always use “green face” (Kao ga aoi) to describe someone who looks pale.

Work Cited

- Burns, Susan L. “Constructing the National Body: Public Health and the Nation in Nineteenth-Century Japan,” in Nation Work: Asian Elites and National Identities, ed. Timothy Brook and Andre Schmid. University of Michigan Press, 2000.

- Davidson, Ellis A. Our Food: A Useful Book for Boys and Girls. Cassell, Peter and Galpin, 1870.

- Fukuzawa, Yukichi. Nikushoku no setsu [On Eating Meat]. 1870.

- Hattori, Seiichi. Tokyo shin hanjō ki [Tokyo’s New Prosperity]. Yamashiroya masakichi, 1871.

- Hitchcock Jr. and Sr. Edward. Elementary Anatomy and Physiology for College, Academia and the other Schools. Ivison, Blakeman, Taylor & Co., 1872.

- Honchō shokkan [Food in Our Country]. 1697.

- Inshoku yōron [A Summary on Diet]. 1874.

- Kanakagi, Robun. Akuranabe: ushi-ya zōdan [The Beef Eaters] Vol. 1. Seishido, 1871.

- Keio University, Fukuzawa Yukichi zenshū [Fukuzawa Yukichi Full Collections], Vol. 17. Iwanami Shoten, 1961.

- Keio University. Fukuzawa Yukichi zenshū [Fukuzawa Yukichi Full Collections], Vol. 19. Iwanami Shoten, 1962.

- Kudō, Hiroya. Korera byō yobō yōjō-hō yakkai [Notes on Self-care and Cholera Prevention]. Gorakudō, 1877.

- Kunaicho. Meiji tenno ki [Emperor Meiji chronicle] Vol. 2.

- Oku,Takenori. Bunmei kaika to minshū [Civilization and Enlightenment and the People]. Shin hyōron Publishing, 1993.

- Sugimoto, Etsu Inagaki. A Daughter of the Samurai. Doubleday, Page & Company, 1925.

- Toki, Yorinori. Keimō yōjō kun [Primer on Health Cultivation]. Suzuki Kiemon, 1872.

- Yamaguchi, Tsuneshichi. Korera byō yōjō no kokoroe [Knowledge on Self-care for Cholera]. Tsuneshichi Yamaguchi, 1877.

- Yamamoto, Yoshitoshi. Inshoku yōjō shinsho [New Book on Dietary Regimen]. 1875).

- Yomiuri Shimbun (multiple).

- Uratani, Yoshiharu. Korera yobō kokoroe hō [Knowledge on Cholera Prevention]. Yoshiharu Uratani, 1877.