The Desire in Question Was Not That of Men

“The two greatest factors that bring gloom to the family are unsatisfied material desires and this unsatisfied sexual desire. If we can fulfill this unsatisfied sexual desire, not only will the woman be saved, but her husband will also be saved, and so will her beloved children.” (Takahashi 1939, 23)

It was with so assertive a statement that dermatologist Takahashi Kiichirō (1885–1967) opened his article in the 887th issue of Nihon iji shinpō (Japan medical journal,1921). By “we” he meant Japanese medical practitioners as a collective. By “this unsatisfied sexual desire” he was referring to married Japanese women’s pleasure in the bedroom, or rather the lack thereof.

Takahashi’s article was published at an eventful time: on 9 September 1939, just after the outbreak of war in the European theater and right as the Japanese Empire itself was two years deep into a full-scale colonial invasion of the Republic of China. When set against the turbulent backdrop of imperial Japan’s ongoing war and war mobilization effort, female sexuality does not readily come to the fore as an issue in historical analyses of women’s desire within marriage as a good and faithful wife. On the Japanese home front, the two decades leading up to the Pacific War of 1941 did feature anxious interpretations of female sexuality: depictions of the “new woman” and “modern girl” who ventured outside the domestic space were prevalent, as were the allegedly deviant “poison woman (dokufu)” and “immoral” sex workers (Yuki 1997; Inoue 1998; Mackie 2003; Silverberg 2006; Marran 2007). Studies of female sexuality behind the frontlines of the Imperial Japanese Army conventionally focus the spotlights—and rightfully so—on systematic violence against women and the complicity of male sexual desire (Tanaka 2003; Frühstück 2022). In comparison, women’s sexual satisfaction within marriage has yet to draw much scholarly attention.

Despite being a somewhat niche topic, married Japanese women’s sexuality inspired at least one enduring discourse through the 1920s and 1930s. Related discussions trickled in mainstream medical journals and popular women’s magazines alike. The major concern was with fukanshō, a type of frigidity defined in terms of the insufficiency of pleasure experienced during sexual intercourse. While the concept was technically applicable to all genders, it functioned in reality as a diagnosis more commonly reserved for women, and not just any woman, but a married one who seemed unable to orgasm by means of intercourse with her husband.

The Myriad Causes of Fukanshō Were Not All Medical

Alongside other sexual and reproductive health concerns, fukanshō began to make casual appearances on the advertisement pages of general interest magazines no later than the first decade of the twentieth century. By the 1920s, it had found its way into the health column of major women’s periodicals (Ishizaki 1927) and the Q&A section of reputable medical journals (Nemoto 1925). One explanation for the condition’s growing publicity pertains perhaps to logistics, namely, the increasing efficiency and influence of mass communication. The evolving consumer culture of the 1920s gave rise to a number of highly popular women’s magazines such as Shufu no tomo (Friends of housewives, 1917) and Fujin kurabu (Woman’s club, 1920). As one of the most far-reaching professional journals on the news and trends of the Japanese medical society, Nihon iji shinpō came into being around the same time in 1921.

A graduate of the prestigious Tokyo Imperial University, Takahashi Kiichirō charted a long and respectable career, and was by no means an anomaly in finding fukanshō a worthy topic for discussion. Many of his like-minded peers hailed from equally elite professional pedigrees, including gynecologists Nakajima Kiyoshi (1901–1962) and Fujii Kichisuke (1903–1987), as well as pioneering female physicians such as Yoshioka Yayoi (1871–1959), Takeuchi Shigeyo (1881–1975), and Ide Hiroko (1896–unknown). All received training in Western medical science, yet the factors they had identified as contributing to fukanshō were neither purely medical nor resolvable by scientific methods alone.

Takahashi, who had written multiple articles and one monograph on fukanshō by 1939, divided the condition’s potential causes into three categories. These consisted of A) organic diseases of the reproductive system (e.g., pelvic inflammatory disease), B) organic diseases of other biological systems (e.g., as a result of morphine overdose), and C) causes of a psychological origin (e.g., vaginismus) (Takahashi 1938, 11). In exploring different types of fukanshō, Takahashi ranked women who never harbored any desire for and experienced no pleasure through sexual activities as the most difficult to treat, for they had a case of “complete fukanshō” (Takahashi 1938, 12). Although Takahashi viewed conditions like hysteria or neurosis as possible culprits, he did not view all psychological explanations for the condition as pathological. Notably, he suggested that if a woman had sexual desire and could experience some sexual pleasure but failed to orgasm, all it might take to solve the problem was simply to explore and find her “erogenous zone.” For example, “there are women who didn’t reach orgasm through regular ‘coitus’ but did so when men nibbled their ears. That was because those women’s erogenous zone was located around ears” (Takahashi 1938, 15).

Other physicians attributed the potential causes of a wife’s fukanshō to her husband and the couple’s relationship. While Nakajima Kiyoshi favored dichotomy in his classification and divided fukanshō into primary and secondary types, the gynecologist also argued that causes of the condition should be sought in the husband as much as in the wife. An ignorant or egoistic husband, for instance, might fail to appreciate that it took different amounts of time for he and his wife to each become sexually aroused. Hinting at the importance of foreplay, Nakajima further stated that husbands “should give their wives sufficient time to prepare,” and acknowledged the husbands’ “need to provide ‘service’” or “a vorspiel” for their wives (Nakajima 1939, 25). On the wife’s part, Nakajima considered fears of pregnancy and its complications as a potential trigger for fukanshō. Alternatively, a wife might experience the condition specifically towards a promiscuous or adulterous husband, a reflection of her worries about contracting venereal diseases from him (Nakajima 1939, 25–26).

The Wife Incapable of Enjoying Intercourse Masturbated as a Maiden

Perhaps counterintuitively, Nakajima also proposed that fukanshō could originate from the wife’s history of masturbation. For him, the rationale behind this causality was technical. Specifically, if a woman had learned to masturbate before marriage, fukanshō might occur due to a difference in the “rhythm” of masturbation vis-à-vis intercourse, and it could accordingly be resolved by synchronizing the pace of the two activities (Nakajima 1939, 25). Nakajima was not alone in linking a wife’s inability to enjoy sex with her husband to her ability to enjoy sex on her own. A fellow male gynecologist, Fujii Kichisuke also listed a wife’s habit of masturbation as a cause of fukanshō. “There is a deep connection between fukanshō and masturbation. In a lot of cases, fukanshō manifests during ordinary intercourse among women who have a habit to masturbate” (Fujii 1939, 29).

Female physicians were not necessarily more understanding when it comes to women’s masturbation. Yoshioka Yayoi, the founder of the first medical school for women in Japan and an activist for women’s rights, openly condemned the act, calling it a “bad sexual habit” (Yoshioka 1926, 62). Speaking from her experience answering female readers’ questions through the health column of the women’s magazine Shufu no tomo, as well as the cases she encountered as a medical educator and provider, Yoshioka described masturbation as a major cause for women’s fukanshō during marriage. Among all the consultation requests she regularly received from the magazine’s women readers about the consequences of masturbation, her primary concern pertained to women who habitually masturbated before—and thereby developed fukanshō after—marriage (Ibid). For Yoshioka, a wife’s ability to please herself was to blame for her incapability to enjoy sex with her husband. The act of female masturbation itself was less a technical hiccup than a character flaw.

Matters within Families, Big and Small

The limited and selected review of imperial Japanese physicians’ perceptions of fukanshō in this essay neither attempts nor provides an answer to what the condition should or would be called today. What I hope to achieve, however, is to shed some light on the married life of Japanese women whose fears about reproductive health and whose frowned-upon enjoyment of masturbation resounded through physicians’ health communication engagements, case notes, and/or journal publications.

At a time when women were expected to enter matrimony as virgins, married women were considered the default demographic group of fukanshō patients. Yet, instead of seeing the causes of fukanshō as exclusively pathological and located in the wife’s mind and body, some physicians actively explored the husband’s responsibilities and failures to cultivate sexual compatibility, while others confronted the challenging realities of venereal diseases and maternal care in imperial Japan.

Takahashi, who had elevated the elimination of fukanshō to the salvation of Japanese families, served as such an example. In 1937, the publication of his monograph on the condition coincided with the Ministry of Education’s release of Kokutai no hongi, or “Essence of the national entity,” a text that would later earn notoriety for canonizing the political ideology that helped organize an empire at war. According to the latter’s teachings, “family” not only constituted the foundation of national life but also embodied the Japanese state—a great family headed by the Imperial House and revered by its filial subjects-as-children.

Ironically, Takahashi’s book quickly made the list of publications banned by the Police Affairs Bureau of the Home Ministry (Naimushō 1939, 62). In 1938, the imperial government also decreed censorship policies to restrict advertisements for women’s fukanshō treatments in newspapers and women’s magazines as part of the war mobilization campaign (Uchikawa 2004, 139, 158). Despite its official propaganda to portray the Japanese state as one big family, what happened—or did not happen—in individual Japanese families’ bedrooms was deemed too obscene for the public at the time of war.

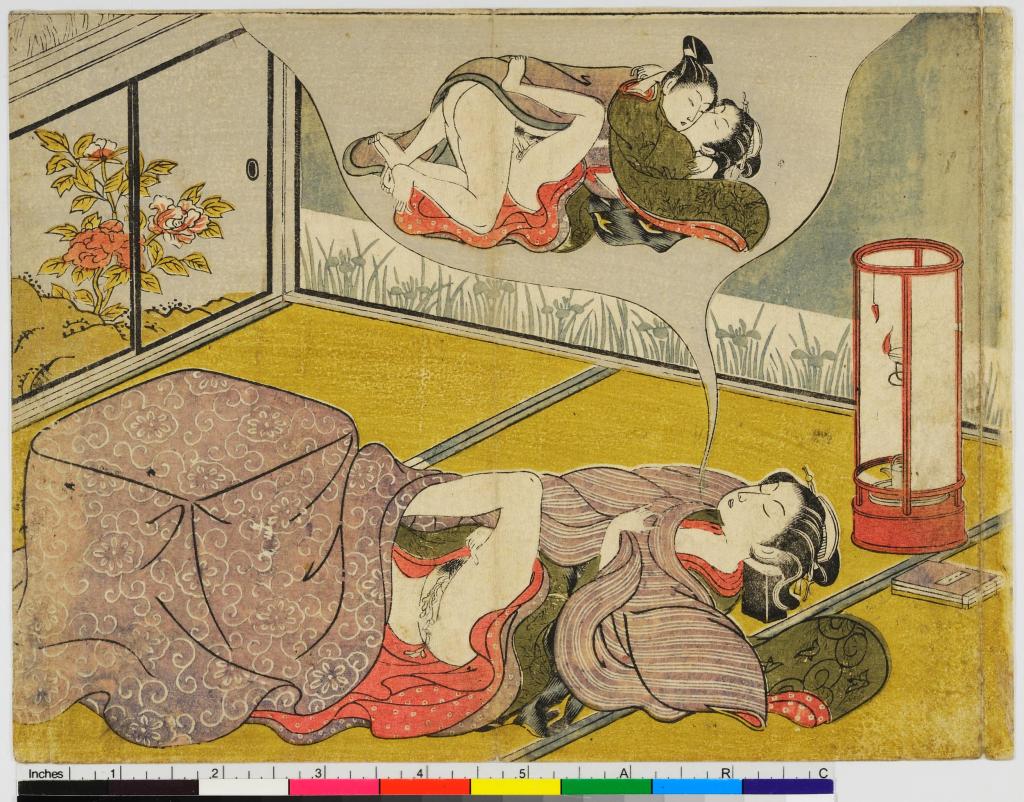

Featured Image

Suzuki Harunobu. c.1770. print; shunga. Colored woodblock print on paper, 18.70 x 25 cm, © The Trustees of the British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_OA-0-83 (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)(The woodblock print depicts a woman fantasizing about intercourse while satisfying herself through masturbation.)

Works cited

Frühstück, Sabine. 2022. Gender and Sexuality in Modern Japan. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fujii Kichisuke. 1939. “Fujin no fukanshō ni tsuite.” Nihon iji shinpō, no. 887 (September): 29.

Inoue, Mariko. 1998. “The Gaze of the Café Waitress: From Selling Eroticism to Constructing Autonomy.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, no. 15: 78–106.

Ishizaki Chūzaburō. 1927. “Sanfujinka sōdan.” Shufu no tomo 11 (8): 304–305.

Mackie, Vera C. 2003. Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment, and Sexuality. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Marran, Christine L. 2007. Poison Woman: Figuring Female Transgression in Modern Japanese Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Naimushō keihokyō [Home Ministry Police Affairs Bureau], ed. 1939. Kinshi tankōbon mokuroku, Shōwa 10nen–13nen. Tokyo: Kokuritsu kokkai toshokan [National Diet Library].

Nakajima Kiyoshi. 1939. “Fujin reikanshō mata wa fukanshō no gen’in oyobi chiryō.” Nihon iji shinpō, no. 887 (September): 24–26.

Nemoto Toyoharu. 1925. “Fukanshō no ryōhō.” Nihon iji shinpō, no. 157 (May): 28–29.

Silverberg, Miriam Rom. 2006. Erotic Grotesque Nonsense: The Mass Culture of Japanese Modern Times. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Takahashi Kiichirō. 1938. “Fujin no fukanshō ni tsuite.” Nihon iji shinpō, no. 805 (February): 10–12, 15–16.

———. 1939. “Fujin fukanshō no ryōhō.” Nihon iji shinpō, no. 887 (September): 23–24.

Tanaka, Toshiyuki. 2003. Japan’s Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution during World War II and the US Occupation. New York: Routledge.

Uchikawa Yoshimi. 2004. Gendaishi shiryō. Vol. 41. Tokyo: Misuzu shobō.

Yoshioka Yayoi. 1926. “Seiteki akushū ni nayamu fujin no shitsumon ni kotaete.” Shufu no tomo 10 (6): 62–63.

Yuki, Fujime. 1997. “The Licensed Prostitution System and the Prostitution Abolition Movement in Modern Japan.” Positions: Asia Critique 5 (1): 135–171.