You cannot breathe; the world slows down around you; your chest tightens as you walk to your car. Once again, you feel as though you have failed to convince a doctor of your pain, and once again, you must face it alone.

This is, unfortunately, the experience of far too many female patients, but the fault does not lie with them.

In this brief essay I contemplate the lived impact that the legacy of the ‘hysterical female’ has on the female patient today. Specifically, I aim to consider how this legacy impacts her ability to have her pain validated.

My life has been filled with what I thought were unique and unfortunate healthcare experiences. From being told, “everyone is sore after skiing,” by my doctor, only to find out days later that my leg was broken, to walking on a broken foot for four months before receiving care because I developed a mistrust of my own ability to judge my pain as a result of continued invalidation I received from biomedical (western biology-based medicine) practitioners. I began to feel that I was not performing my pain in a legible way to my practitioners. I couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong.

As a female who has experienced this biomedical gaslighting, I have found myself questioning what was wrong with me that I failed to convince doctors of my pain. As a result of experiencing this time and time again, I believed the problem was me.

The Invisibility of Female Pain

Then, I read patient narratives written by female patients and saw my experiences reflected in their stories. So many other women relaying similar experiences of struggling to receive validation for their pain and in ways that prolonged illness, increased severity and even led to death (see provided list below for examples of such narratives). After reading statements such as these,

Soon, my periods got so bad that I’d sometimes pass out five or six times in one morning. Soon, my parents had to hold up my body so that if I passed out while vomiting I wouldn’t choke. It was clear to me and to my parents that I wasn’t faking. Still, none of the doctors believed me, exactly. (Bolden 54)

As I walked out of the ICU, I felt that old state of mind consuming me, taking me back to my time in so many other hospitals, and the anger at being misunderstood boiled up in me again, that feeling of not being taken seriously by those who had your life in their hands. All the many times, the people who shook their heads at Lyme, who looked at me with pity for my circumstances, who could barely stifle their rolled eyes. I’d tried to avoid this hostile world of hospital rooms and doctors’ offices for years, but it haunted me. (Khakpour 22-23)

the inability of western medicine to see female pain became clear to me. The fault is not with these women or myself as one of them, but rather with the expectations of how a female body should act when in pain. This is when I began to contemplate the performance of pain. How much is what we do in the place of the clinic (or other biomedical spaces) a performance where the roles are patient and practitioner, and the act is to try and communicate an invisible experience taking place within one’s own body to another?

So, what does it mean to perform pain? Why is it that western medicine struggles to see when the female body is in pain? What is it that renders her pain invisible?

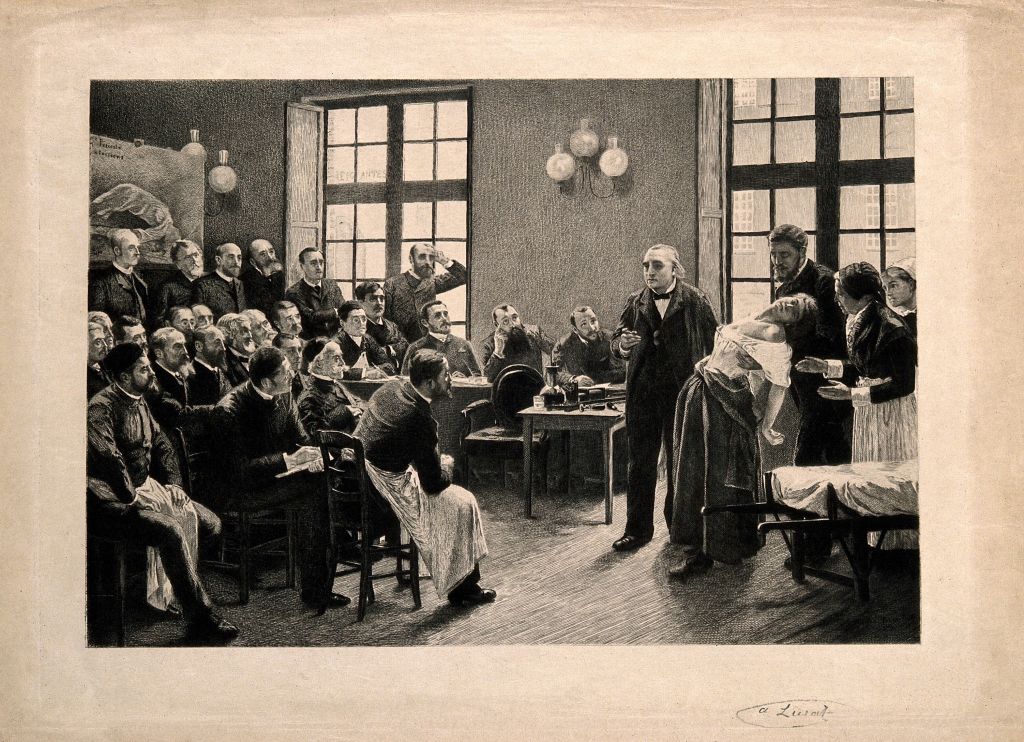

History of Hysteria

Perhaps it is the legacy of the history of the hysterical female. Hysteria was “coined in 1900 BC—almost 4,000 years ago–to describe inexplicable symptoms in women” (Dyck 1999, 124). It became a catch all diagnosis for practitioners, and in doing so, began to establish beliefs that the female was simply emotional, irrational, or delirious due to the inability to identify or otherwise scientifically explain her symptoms (while in reality this might be due to the fact that, historically, medicine and science studied male bodies see Liu and DiPietro Mager; Simon; Dwass). Ailments such as the “wandering womb,” the idea that many of women’s illnesses were a result of the uterus moving within her, serve as an example of how hysteria shaped the biomedical lens to see women through this hysterical gaze (Thompson 31). These ideas, while debunked today, cloud the biomedical gaze, obscuring its view of the female body.

In thinking about pain as a performance, in that physicians are trained to identify certain physical cues or behaviors to inform their assessment of a patient’s pain, consider how this history of thinking about the female body as hysterical created a foundational script for how to interpret the female body.

A Hysterical Script

In her book Gender Trouble (1990), Judith Butler posited the idea of a social script to conceptualize the social expectations embedded in our societies that dictate how a person should behave given their body. Her work urges us to consider how societal performances are scripted and how connecting those performances with particular scripts illuminates a deeper understanding of the ways in which we come to embody culturally shaped subjectivities (Butler).

Through this framing, how does this script of the hysterical female, a culturally shaped subjectivity, play a role in the female experience in western medicine? How does this contribute to the invisibility of her pain? Isabel Dyck, a health geographer, suggests that, “the biomedical ‘scripting’ of the body provides an authoritative set of descriptions and meanings through which to interpret the women’s struggles with their bodies” (127). This script, which provides a guide for interpreting the female body, is tainted with the historical biases of the hysterical female. In interpreting the female body through this script, instead of seeing her pain, her emotions and sanity are questioned first.

For example, in their article The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias Against Women in the Treatment, Hoffman and Tarzian recognize that “[w]omen are also portrayed as hysterical or emotional in much of the medical and other literature” (20). This underlying script of hysteria places a subconscious seed of doubt in the minds of contemporary physicians, where they question the validity of the female patient’s pain. Questions such as is it stress, depression, or anxiety remain influential in assessing female pain. Yet, at the same time, if the female patient claims to be in pain and she is not emotional, her pain is also questioned (see Hoffman and Tarzian 20).

Performing Female Pain

So, what does she have to do to have her pain seen? To be validated? Should she perform this script of hysteria? Should she cry? Scream? Be inconsolable? Unable to walk? Sometimes this might work. In her patient narrative Abby Norman lives this history as she feels her pain is not seen because she is not performing it in a way that is visible.

I sat slumped in a chair in the intake room. At first the nurse in triage seemed doubtful of my pain, because I was so subdued from all the crying that I just stared, glassy-eyed, at the wall. As she took my blood pressure, she seemed dubious. I had reported that the reason for my visit was a frightening amount of abdominal pain, and I guess she expected me to be screaming and rolling around on the floor. But the pain had exhausted me to the point of surrender. (Norman 11)

Perhaps if she performed this female hysteria script correctly, her pain would have been validated. However, it is also equally as possible that she might be seen as hysterical and, therefore, invalid. This script that writes the female body as hysterical can impact women’s biomedical experiences in both ways. It can make her invisible if she is not acting emotional in response to her pain because it is believed that if she was in such pain, she would be emotional. But because hysteria also suggests irrationality, madness, or delirium, performing this script can also render her invalid.

The history of hysteria contributes to the invisibility of female pain today. Considering the impact of this history draws attention to the difficult situation of the female body in places of biomedicine. In these biomedical places, where the biomedical gaze is the lens through which practitioners view their patients, her validity is obscured by this history of hysteria. Within these places, when the female patient performs pain, she risks being read as either too emotional or not emotional enough. She might have her pain validated, if she performs this hysterical script in a way that is recognized and accepted by her practitioner, or she might just be judged as hysterical.

So, what can a female body do?

Selected Patient Narratives:

Norman, Abby. Ask Me About My Uterus: A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women’s Pain. PublicAffairs, 2018.

Bolden, Emma. The Tiger and the Cage: A Memoir of a Body in Crisis. Soft Skull Press, 2022.

Parker, Lara. Vagina Problems. Griffin, 2020.

Cahalan, Susannah. Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness. Reprint edition, Simon & Schuster,

2013.

Khakpour, Porochista. Sick: A Memoir. 2018.

Manguso, Sarah. The Two Kinds of Decay: A Memoir. First edition, Picador, 2009.

Radner, Gilda. It’s Always Something. Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Works Cited:

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1990.

Dwass, Emily. Diagnosis Female: How Medical Bias Endangers Women’s Health. Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

Dyck, Isabel. “Body Troubles; Women, the Workplace and Negotiations of a Disabled Identity.” Mind and Body Spaces, edited by Ruth Butler and Hester Parr, Routledge, 1999.

Hoffmann, D. E., and A. J. Tarzian. “The Girl Who Cried Pain: A Bias against Women in the Treatment of Pain.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics: A Journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 29, no. 1, 2001, pp. 13–27. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-720x.2001.tb00037.x.

Khakpour, Porochista. Sick: A Memoir. 2018. bookshop.org, https://bookshop.org/p/books/sick-a-memoir-porochista-khakpour/6436954.

Liu, Katherine A., and Natalie A. DiPietro Mager. “Women’s Involvement in Clinical Trials: Historical Perspective and Future Implications.” Pharmacy Practice, vol. 14, no. 1, Mar. 2016, pp. 708–708. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2016.01.708.

Norman, Abby. Ask Me About My Uterus: A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women’s Pain. PublicAffairs, 2018.

Rogers, Wendy A., et al. “Exclusion of Women from Clinical Research: Myth or Reality?” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 83, no. 5, May 2008, pp. 536–42. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.4065/83.5.536.

Simon, Viviana. “Wanted: Women in Clinical Trials.” Science, vol. 308, no. 5728, June 2005, pp. 1517–1517. www-science-org.www2.lib.ku.edu (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1115616.

Thompson, Lana. The Wandering Womb: A Cultural History of Outrageous Beliefs About Women. Prometheus Books, 2012.

Image Credit:

Jean-Martin Charcot demonstrating hysteria in a hypnotised patient at the Salpêtrière. Etching by A. Lurat, 1888, after P.A.A. Brouillet, 1887. Source: Wellcome Collection.