Kathryn Cai

As a recent New York Times article notes, apocalyptic narratives—in the form of natural disasters and conflict with North Korea, for instance—and survivalist responses to it are on the rise in popular US discourses.[1] This tongue-in-cheek article notes that survivalism is gaining traction in young, affluent culture, “where the bombproof bunker has replaced the Tesla as the hot status symbol for young Silicon Valley plutocrats” and the “‘prep’ in question [might] just mean[] he is stashing a well-stocked ‘bug-out bag’ alongside his Louis Vuitton luggage in a Range Rover pointed toward Litchfield County, Conn.” In addition to the US-centric and classed valences this portrayal satirizes, these masculine pronouns and male-dominated spaces suggest that the notion of apocalypse continues to be inflected with masculinity.[2]

Samantha Hunt’s recent short story collection The Dark Dark (2017) contains a story that begins in a nuclear missile silo during the Cold War. The men in the silo are assigned to “push the button when it came time for nuclear apocalypse,” which never materializes. The story jumps into the present, when one of the men, Wayne, works for the FBI and has developed an extremely life-like female cyborg to seduce and kill a man, currently living in an isolated cabin, with utopian revolutionary designs in the vein of the Unabomber, against a technology-driven society with a vision of an idealized agrarian society. Hunt’s cyborg woman is not a mere automaton; though she is programmed to obey Wayne’s commands, including unspoken ones such as “not to resist male advances,”[3] she also possesses desires and awarenesses that leave a trace in her consciousness even while she cannot act directly on them. When the target of their mission, who is unaware of her cyborg nature, asks her what she wants, her mind flashes to “‘Detonation’ […] but that result lies beyond her firewall, along with all the other essential truths about herself that she isn’t allowed to reveal.”[4] The story’s ending, however, suggests that she exercises an ambiguous and inchoate influence on the outcome of her narrative. Though Wayne is meant to detonate her inside the cabin, he waits for her to return before wrapping her in a loving embrace that she is “programmed not to resist.” Only then does he finally “speak[] words of loving sweetness into her ear, the ones she’s been waiting to hear […] that send a repressed tremor through the quiet night.”[5] Though she appears to be the puppet of a national security/war-making apparatus intertwined with male sexual desires, she also obtains the fate she desires. The question of how remains ambiguous, and this is precisely the point. Her latent agencies suggest themselves throughout the story in moments that are not clearly causal and that simultaneously enfold her within the apparatus of control. They nevertheless, however, give the reader a sense that her fate is more than chance. Though not direct, autonomous action, agency can take shape through other more threatened, liminal, even inarticulable avenues.

Hunt’s mechanically constructed woman and the compromised agencies she embodies call to mind Donna Haraway’s famous construction of the cyborg in “A Cyborg Manifest” (1984), as a figure who refuses the masculinist “tragedy of autonomy” that is “tempered by imaginary respite in the bosom of the Other.”[6] Hunt’s cyborg might challenge the limits of Haraway’s concept, which elaborates on the close and mutually redefining relationship between humans and nonhuman entities. Haraway sees promise in a “cyborg feminism” that, in embracing the compromised transformations of science and technology that are fully imbricated in power, also refuses the imperatives of gendered dichotomies and discourses, including feminist discourses, that continue to strive for fatal illusions of universalization and totalization. While masculinist fantasies of autonomy and totalized feminist discourses are similarly “ruled by a reproductive politics—rebirth without flaw, perfection, abstraction” that promote essentialist constructions of women,

there is another route to having less at stake in masculine autonomy, a route that does not pass through Woman, Primitive, Zero, the Mirror Stage and its imaginary. It passes through women and other present-tense, illegitimate cyborgs, not of Woman born, who refuse the ideological resources of victimization so as to have a real life. [7]

Hunt’s cyborg figure presents a limit case of such identification and the blurring between human and nonhuman, natural and unnatural. Her desires and actions maintain the traces of these categories within their blurring as questions, asking what it means to designate not just bodies but also impulses, desires, actions, and affects as human or nonhuman or even if this designation remains relevant. Rather than human/nonhuman, Hunt points out that gendered valences, even divorced from human bodies, remain determinative for imaginations of destruction, domination, and power and central to noticing compromised agencies within these structures.

This vein of gendered cyborg questioning and categorical disruption departs from the portrayal of other female cyborg figures in scifi such as Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) and Richard Powers’s Galatea 2.2 (1995), whose femininized figures do not challenge the gendered paradigms that create and control them. At the same time, it also challenges the limits of feminist identification in the present. As the implications of Haraway’s cyborg suggest, we might extend the limits of humanist and gendered identifications to ask after the other agencies that share kinship with other nonhuman and machine entities. Jennifer Egan’s female protagonist in her short story “Black Box” (2012), which was first released as a series of tweets, similarly combines embodied technology and femininity with militaristic deployment, though she is of human origin. Meanwhile, in Chang-rae Lee’s dystopian post-apocalyptic novel On Such a Full Sea (2014), his protagonist Fan extends attention to these blurred boundaries to another extreme; rather than human qualities in nonhuman or hybrid technologized form, Fan is a biological human figure of Asian origin who embodies affects and agencies that might be deemed cellular or mechanical. She reminds us of the harm and disempowerment that association with these nonhuman entities can cause by evoking common stereotypes of Asians as machine-like, even while she also transforms these same stereotypes into a different model of agency that is not reliant on designations of humanist subjectivity, on which I will elaborate next.

—

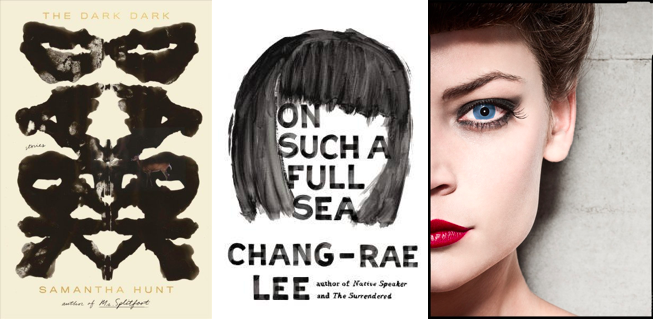

Images above: Cover of Samantha Hunt’s The Dark Dark; cover of Chang-rae Lee’s On Such a Full Sea; associated image with Jennifer Egan’s Black Box, published in The New Yorker, photo by Dan Winters

[1] Alex Williams, “How to Survive the Apocalypse.” New York Times September 17, 2017.

[2] Teresa Heffernan, Post-Apocalyptic Culture: Modernism, Postmodernism, and the Twentieth-Century Novel. (University of Toronto Press, 2008), 14.

[3] Samantha Hunt, “Love Machine,” The Dark Dark. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017), 127-46.

[4] Ibid., 145.

[5] Ibid., 146.

[6] Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” The Cybercultures Reader. Ed David Bell and Barbara M. Kennedy (Routledge, 2000), 291-324; also see Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Free Association Books, 1991.

[7] Ibid., 313.