Jessica M. E. Kirwan

Cosmopolitanism and tenacity were required attributes of the first British women doctors.

In late nineteenth-century England, after much struggle, women began increasingly to attend colleges, including medical school, and to enter the professions. The first English woman doctor was Elizabeth Blackwell, who obtained her degree and practiced medicine in the United States where the “medical women movement…was at least 20 years ahead of its British counterpart.”1 In England, Blackwell was followed by Elizabeth Garret Anderson, who pushed her way through medical classes, studied privately to obtain certificates, and earned a medical license in 1865 from the Society of Apothecaries who could not discriminate against her per their charter. Anderson eventually obtained a medical degree from the Sorbonne in Paris in 1870. By this time, some women had been practicing as physicians or other medical professionals but without the official licenses and degrees, something men did as well. Parliament passed the Medical Act of 1858 as an attempt to eliminate this practice by forcing licensed doctors to register with the government. Owing to this required legitimacy, women began studying medicine in Europe as a way to become licensed doctors in England (although whether England would accept international medical degrees became another hotly contested issue). Nevertheless, it would be seven more years before another woman was granted a medical license, which would go to Sophia Jex-Blake and three others belonging to the Edinburgh Seven, the first seven women allowed admittance into the University of Edinburgh’s medical school; of the Edinburgh Seven, these first four who registered as doctors had actually graduated from the Irish College of Physicians in 1877.

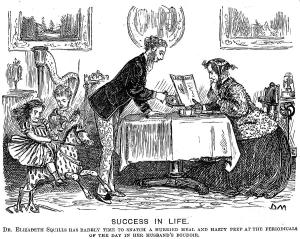

The debate over the appropriateness of women obtaining medical degrees took place not only in Parliament and at universities but also domestic settings where women had to convince their mothers and, mostly, fathers to support their career choice; it took place in medical journals like The Lancet and the British Medical Journal; and it took place in laymen periodicals like The Times and Punch. Take, for instance, Charles Keene’s Punch cartoon, “The Feminine Faculty” (shown above) which depicts a woman doctor as a man in drag, or “Success in Life” (shown below ) which presents a domestic scene of gender role reversal wherein the patriarch of the family watches over the children in his boudoir while his doctor-wife reads the paper; the son’s and daughter’s roles are also reversed with the former playing the harp and the latter riding a toy horse.

“Woman’s Triumph in the Profession” (shown below) suggests it takes several women to accomplish the work one male dentist, which, considered alongside the other cartoons, exemplifies the bind women were in. She may look like a man, but she’s not as strong as a man. Ledger suggests that, “it was new practices in the education of women which were blamed by many enemies of the New Woman for her supposed masculinization.”2 Although women doctors were carrying on with work that they had been doing domestically before modern times, the idea of a women receiving a medical degree and participating in other activities associated with doctors, such as working outside the home or putting patients before family, spawned new anxieties about notions of femininity and masculinity at the end of the nineteenth century.

At stake was the belief over whether women had equivalent intellectual, physical, and emotional ability to men, as well as whether women had different abilities that might make them better suited for the medical profession than men. Central to the argument for allowing women in medical schools was the idea that women had long been healers, before the existence of medical schools.3 More importantly, and this is what drove many women doctors, life itself was at stake through the advancement of women’s health, which seemed unlikely to happen but for the work of women. The medical issues from which British women suffered—such as sexually transmitted diseases like syphilis (typically spread by men) and death during childbirth (childbirth having become increasingly medicalized and invasive under British male doctors who were replacing “illegitimate” midwives) were going largely ignored.

Just as they needed healers, women had long been healers, but to advance women’s health, they also needed access to medical technology, patients, hospitals, education, and the support of men. Fortunately, women’s health became a pet cause of Queen Victoria towards the end of the century when she came to learn that many of her female Indian subjects were suffering from medical issues for which they could not be treated because of purdah, the Hindu practice of secluding women, which often precluded them from proper medical care when the only physicians available were men. Purdah provided British women patients who had no other options for medical assistance but a woman physician. In their bibliography of women in medicine, Chaff, Haimbach, Fenichel, and Woodside reference 55 articles and books on medical missionary work written by women physicians and published during the last decade of the nineteenth century.

The women who became legitimately recognized doctors in the British Empire at the end of the nineteenth century were a privileged class of white women from the United States and Europe. Many of them were evangelical. And many of them practiced in the colonies. Women physicians were transmitters of British medical practices and Western science across the empire, culture changers who offered alternatives to native customs. But the colonies likewise offered much to these women. As Narin Hassan writes,

[W]omen negotiated and engaged within the project of empire through their privileged access to domestic native spaces and cultural traditions and their representations of them, but…[also for these women,] access to the discourses of modern medicine resulted in the production of a new realm of women’s “work” overseas that could allow women to…challenge and shape…the field of colonial medicine. Women travelers were influenced and regulated by medical ideas at the same time as they borrowed, applied, and sometimes shaped them…The inclusion of women in colonial realms simultaneously challenged, restructured, and influenced imperial progress while women often bore the burden of serving as examples of English cultural norms. Within colonial spaces women could function as active agents of cultural exchange, particularly within the domestic realm.4

By the late nineteenth century, the role of women in medicine became intertwined with travel and colonialism and, as such, the ability of women to perform a societal function within British culture that was already performed by men became inextricably tied to the subjugation of the native populations of the British colonies, a prerequisite not relevant to men. The analysis of medical women in literature has frequently relied on understanding this union of medicine and race much more so than is required in our understanding of men’s contributions to medicine.

Image Credits:

All images produced before 1923, and thus believed to be in the public domain in the US.

Figure 1: Wood engraving titled ‘The Feminine Faculty’ 24 May 1873 Presented by Mrs P. Keene, October 1976. http://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/TGA-766-197-1. Caption retrieved from https://magazine.punch.co.uk/image/I0000h.2nBhiK5II.

Figure 2: https://photos.com/featured/success-in-life-1867-artist-george-du-print-collector.html

Figure 3: https://spartacus-educational.com/History_Visual_December.htm

References

- Blake, Catriona. The Charge of the Parasols: Women’s Entry to the Medical Profession, The Women’s Press Ltd., 1990.

- Ledger, Sally. The New Woman: Fiction and Feminism at the Fin de Siècle, Manchester University Press, 1997.

- See “Medical Women,” two essays by Sophia Jex-Blake published in 1872.

- Hassan, Narin. Diagnosing Empire: Women, Medical Knowledge, and Colonial Mobility, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2011.