The path from scholarship on male doctors in Victorian literature to that of women doctors was a somewhat circuitous one, the road having been laid more as a result of a growing interest in the fin-de-siècle New Woman than in literary representations of medical professionals in fiction or symbolic representations of anxieties about disease. In the mid to late twentieth century, we saw a surge in scholarship about literary representations of physicians in Victorian literature, and it typically focused on male characters in canonical works by male authors like Bram Stoker, Arthur Conan Doyle, H. G. Wells, and Wilkie Collins. More recently, scholars began to examine the character of the doctor in Victorian literature by women authors [1]. Among the burgeoning scholarship on Victorian women writers and New Woman characters at the end of the last century there developed an interest in how women doctors were written about as well as what they wrote about. While there was some commentary on such works closer to when they had been written, having been absent from the canon, these works have been mostly overlooked.

Take, for instance, Sydney C. Grier’s 1897 novel Peace with Honour. Just one of a few late nineteenth-century works of fiction centering on the woman doctor, the plot involves the negotiation of a trade agreement between a fictional Ethiopian kingdom named Khemistan, which is in inner turmoil, and the British government. One hero of the story is a woman doctor, Dr. Georgia Keeling, who takes part in this mission to Ethiopia so that she can cure the Ethiopian queen’s cataracts. The queen lives in seclusion as part of a harem. Georgia Keeling’s purpose in participating in this mission is secondary to the trade treaty, which is being negotiated by her childhood-friend-cum-colonial-diplomat Dick North, who, amongst other diplomats, works under the direction of Sir Dugald. Early in the novel, the mission’s male physician is poisoned to death by the king. Then, Sir Dugald is poisoned by the king. When he enters a coma, Georgia becomes an invaluable and trustworthy member of the mission as she is able to treat and revive him. Another character central to the story is Sir Dugald’s wife, Lady Haigh, who becomes a sage-like friend of Georgia’s amidst her own distress about her husband. Interwoven with this adventure story is a love story about Georgia Keeling and Dick North, who, it should be noted, opposes women doctors in general, a character trait that creates a contentious romance between the two, resembling the romances of Jane Austen.

One hero of the story is a woman doctor, Dr. Georgia Keeling, who takes part in this mission to Ethiopia so that she can cure the Ethiopian queen’s cataracts. The queen lives in seclusion as part of a harem. Georgia Keeling’s purpose in participating in this mission is secondary to the trade treaty, which is being negotiated by her childhood-friend-cum-colonial-diplomat Dick North, who, amongst other diplomats, works under the direction of Sir Dugald. Early in the novel, the mission’s male physician is poisoned to death by the king. Then, Sir Dugald is poisoned by the king. When he enters a coma, Georgia becomes an invaluable and trustworthy member of the mission as she is able to treat and revive him. Another character central to the story is Sir Dugald’s wife, Lady Haigh, who becomes a sage-like friend of Georgia’s amidst her own distress about her husband. Interwoven with this adventure story is a love story about Georgia Keeling and Dick North, who, it should be noted, opposes women doctors in general, a character trait that creates a contentious romance between the two, resembling the romances of Jane Austen.

When it was published in 1897, there was little fiction representing a woman doctor as a heroine, but there was even less fiction depicting a heroine abroad, despite how common practicing medicine abroad had become for early woman doctors. Through Peace with Honour, Grier hoped to advance the cause of the New Woman while also upholding Victorian ideals of domestic romance and femininity. The novel’s reprinting a century and a half after its original publication speaks to its success in addressing sexual anxieties at the end of the nineteenth century and its revival as a rich subject of critique.

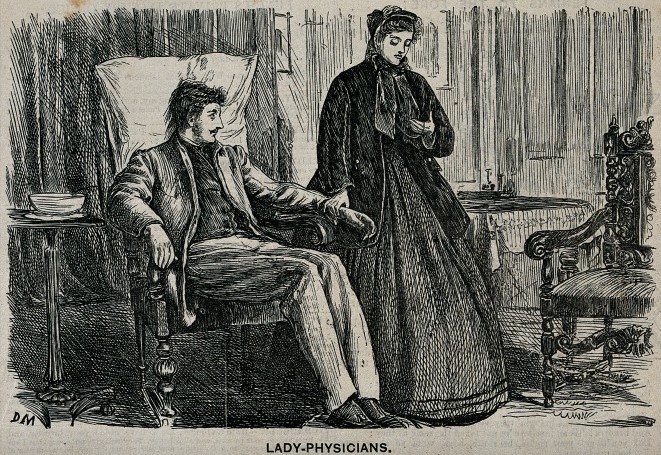

Given all of this, Peace with Honour is very much a novel of its time and genre. Edna Kenton reviewed the brief and short-lived theme of heroine “’Lady Doctresses’” of Nineteenth Century Fiction” in her 1916 article in The Bookman acerbically titled, “The Pap We have Been Fed On.” More than two decades into the emergence of the woman doctor in fiction, Kenton analyzed the few novels representing the woman physician in the late nineteenth century [2]. Kenton’s views are still relevant today in recognizing the problems and shortcomings of some of these works and the successes of others. With tongue in cheek, she gave a modern reading to what she saw as archaic stories, ones that aligned the stereotypes imagined by these narratives with other harmful Victorian stereotypes, like that of the spinster. In addition to its brief commentary, the article provided a useful annotated bibliography of the few representations that existed of women doctors in fiction leading up to the twentieth century. What Kenton found in these works of realist fiction is what the Punch cartoonists had been simultaneously mocking through visual art, that the medical heroine was often somehow masculine, whether in her physical appearance or approach to relationships. Kenton also argued, however, that the heroine doctor, owing to her logical and intuitive mind, understood how to prevent women and girls, including themselves, from appearing or becoming unladylike. As Gail Cunningham says of fin-de-siècle fiction, a “crisis of masculinity” emerged in response to the New Woman, and the discourse surrounding masculinity of the New Woman was taken up both by advocates for and opponents of the New Woman. Many of these fictional New Woman doctors were “cut from the same cloth,” Kenton said, which doubly pointed to the observation that ways of dressing was a central theme in these novels, an important point I will return to in a later post.

Although some of the British and American novels and stories in this genre were written by woman doctors, Grier herself was not a doctor. Little is known about the romance novelist Sydney Carlyon Grier who wrote under the pseudonym Hilda Gregg, but we do know her sister was a doctor and she frequently set her stories in the colonies. In 1898 she published an anonymous piece on “The Medical Woman in Fiction” for Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, a periodical by her novel’s publisher Blackwood. Its anonymity and proximity to the publication of her woman-doctor novel suggests she wrote it more as a marketing piece to bring attention to her novel than a political or literary critique addressing representations of women in medicine. Nevertheless, she made some salient points, highlighting the inadequacies of these fictions in supporting the cause of the woman doctor, as most of them intended to do. Interestingly, she opened the piece with a discussion of fashion to make the point that everything new is typically dismissed at first, speaking to the importance of fashion in the acceptance of new ideas (an idea we see throughout Peace with Honour). Holding her own novel up as unique in that it is the only woman-doctor story to take place in the colonies, and comparing herself to Kipling, Grier applauded herself for proving through fiction that the woman doctor need not abandon marriage and domestic bliss to pursue a career. Grier suggested that, by the time of the article’s writing, the plight of the woman doctor had succeeded, and audiences had accepted that the woman doctor was a modern fact. She also placed the medical profession squarely in the domestic sphere by remarking that “the ideal medical career [is] the joint exercise of their profession by a husband and wife” (109).

Although some of the British and American novels and stories in this genre were written by woman doctors, Grier herself was not a doctor. Little is known about the romance novelist Sydney Carlyon Grier who wrote under the pseudonym Hilda Gregg, but we do know her sister was a doctor and she frequently set her stories in the colonies. In 1898 she published an anonymous piece on “The Medical Woman in Fiction” for Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, a periodical by her novel’s publisher Blackwood. Its anonymity and proximity to the publication of her woman-doctor novel suggests she wrote it more as a marketing piece to bring attention to her novel than a political or literary critique addressing representations of women in medicine. Nevertheless, she made some salient points, highlighting the inadequacies of these fictions in supporting the cause of the woman doctor, as most of them intended to do. Interestingly, she opened the piece with a discussion of fashion to make the point that everything new is typically dismissed at first, speaking to the importance of fashion in the acceptance of new ideas (an idea we see throughout Peace with Honour). Holding her own novel up as unique in that it is the only woman-doctor story to take place in the colonies, and comparing herself to Kipling, Grier applauded herself for proving through fiction that the woman doctor need not abandon marriage and domestic bliss to pursue a career. Grier suggested that, by the time of the article’s writing, the plight of the woman doctor had succeeded, and audiences had accepted that the woman doctor was a modern fact. She also placed the medical profession squarely in the domestic sphere by remarking that “the ideal medical career [is] the joint exercise of their profession by a husband and wife” (109).

Medical rhetoric was well-suited for analogies about gender dynamics at the fin-de-siècle. In her essay on the New Woman, Sarah Grand deployed medical discourse when she suggested that the New Woman, by virtue of her qualities, was a type of sociological physician for she “expos[es] the sore of Society in order to diagnose its diseases, and find a remedy for them” (669). Although the New Woman would “oppose you with a will” she would “then make a salve for your wounded feelings” (Grand 670). Because it was written a few years before Peace with Honour, it almost seems that Grier is bringing Grand’s vision to life through Georgia Keeling.

[1] See, for example, Tabitha Sparks’s The Doctor in the Victorian Novel: Family Practices, which examines works by George Eliot, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Elizabeth Gaskell, and the more commonly analyzed male authors I mentioned.

[2] The characters and novels Kenton analyzes include, A Woman Hater by Charles Reade, Dr. Bolton in Mark Twain and Charles Dudley’s The Gilded Age, Dr. Zay by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, Dr. Breen, a W. D. Howells character, Helen Brent, M. D. whose author is unknown, and Dr. Janet of Harley Street by Dr. Arabella Kenealy. Overlooked by Kenton is the novel by Sophia Jex-Blake’s long-time companion and colleague, Margaret Georgiana Todd, Mona Maclean: Medical Student, written under the pseudonym Graham Travers. Jex-Blake discusses this novel in her essay, “Medical Women in Fiction,” published in Nineteenth Century in 1893.

References

Cunningham, Gail. “’He-Notes’: Reconstructing Masculinity.” The New Woman in Fiction and in Fact: Fin-de-Siècle Feminisms. Edited by Angelique Richardson and Chris Willis, Palgrave, 2001, pp. 94-106.

Grand, Sarah. “The New Woman and the Old.” Lady’s Realm, 4, 1898, pp. 466-470.

Grier, Sydney C. (Gregg, Hilda). “The Medical Woman in Fiction.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 164, July 1898: 94-109.

Grier, Sydney C. Peace with Honour, William Blackwood and Sons, 1897.

Kenton, Edna. “The Pap We Have Been Fed On. VIII—‘Lady Doctresses’ of Nineteenth Century Fiction.” The Bookman; a Review of Books and Life (1895-1933), American Periodicals, vol. 44, no. 3, , 1916, pp. 280-287.