Bennett Kuhn // Around us were dusty stacks of forgotten hardcover books and crowd members circulating in the now-defunct Beaumont Warehouse venue in West Philly. The three-night immersive multimedia art project called Going There was in full swing, and a short queue led up to the table where I sat with two synthesizers welcoming strangers like aural palm readers. The Empathy Chamber was just one component of Going There, which brought nine Philadelphia-based artists in close contact imagining an aesthetic practice based on community building through disclosed vulnerability.

If you had joined me in The Empathy Chamber on one of those nights in 2016, our improvisation might have gone any number of ways. We might have played for only a moment, just long enough for you to get a feeling for the novelty of the Animoog iOS software synthesizer. More likely, we’d have sat there for a few minutes exchanging gestures in sound, admiring the small flickers of choice here and there altering the course of our duet. Listening back to the recordings below, I now hear little moments of decision, signposts of discovery. Above all, we were investigating ways of listening to listening and playing about playing. Awkward semi-steps and pauses, moments of talking over, stuck notes, and other anxious soundings laid a groundwork for exchange on the theme of empathy.

Going There & Bennett Kuhn – The Empathy Chamber (2016)

01 The Empathy Chamber (Sides A & B) (22:26)

On a music stand near The Empathy Chamber’s queue, I had placed a piece of writing about its origins and intent, public signage explaining empathy’s role in the project:

By offering you a chance to share in an improvised synthesizer duet, I am highlighting how we are both playing what we hear innerly and hearing what we play outwardly, choosing not just what notes to play but how to listen to what is being shared. I hope this exercise in active listening and sharing can emphasize the interdependence of all people in redesigning the parameters of free, authentic, and empathetic expression.

-The Empathy Chamber (2016)

Rereading these words, I am reminded of my ambition at the time to push on ‘interdependence’ as a pivotal theme of social engagement. I also read myself as taking empathy to be a tool for highlighting interdependence and showing how empathy makes justice more accessible. The logic was something like, ‘If I put myself in your position, then I understand my position better (in all the ways it is not yours), and by making our contradistinction clearer, both you and I can be better apprised of how to best support one another’s growth (i.e., interdependence).’

My present writing below considers how my thinking about empathy has changed since 2016. In general, I have stepped away from accepting empathy to be an inroad to insight into interdependence and justice. In tracing the evolution of empathy for me, I speculate about what I would change if I were to plan another iteration of The Empathy Chamber.

Though I don’t draw specific connections here to how empathy appears in medical settings, I’m submitting this writing to Synapsis in the hope that readers will acknowledge how empathy is inculcated in the learning and day-to-day functioning of medical and health workers, with a long history going back to at least the 1960s (detailed in part in Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams), and make connections accordingly. The Empathy Chamber brought participatory aesthetic practice and the theme of building or restructuring empathy into an art space. I understand no reason this couldn’t be translated into a traditional setting of care.

1.

A 1983 study titled “The Structure of Empathy” found a correlation between empathy and four major personality clusters: sensitivity, nonconformity, even-temperedness, and social self-confidence. I like the word structure. It suggests empathy is an edifice we build like a home or office—with architecture and design, scaffolding and electricity. The [traditional] Chinese character for listen is built of many parts: the characters for ear and eye, the horizontal line that signifies undivided attention, the swoop and teardrops of heart.

-Jamieson, The Empathy Exams

As musician-in-residency at Synapsis, I am exploring the ancient and enduring liminality between what has been composed (music) and what is used in the work of care (medicine). The Empathy Chamber put forward empathy as a way for strangers and myself to explore our intersections of listening, feeling, thinking, and playing in order to activate, build up, and maybe even shape some of our empathetic capacities.

Two assumptions about empathy stick out to me now in considering the project’s ambitions:

- Music (in some forms) can build empathy for at least some participants. (i.e., aesthetic assumption)

- It is good to be empathetic. People should be more empathetic. (i.e., ethical assumption)

The former (1) was about the feasibility of this project somehow making more empathy. The latter (2) was about what impact I predicted empathy building would have on participants’ communities and the world in general. In researching this essay, I learned about the history of the word empathy and contemporary social critiques of its value. I hadn’t had the time to uncover these conversations before The Empathy Chamber in 2016. Catching up now, I find myself challenging both of the above assumptions.

Regarding (1), in describing The Empathy Chamber I used words like ‘foster’ and ‘generate’ to give the sense that empathy can not only be molded and shaped like a piece of plastic but also increased in quantity and maybe reshaped, like a battery you not only can recharge but also sculpt like putty in order to maximize its capacity.

This assumption was built into the mechanics of how I framed The Empathy Chamber for participants. Motivating strangers to open up to considerations of their own emotional capacities, I choose to disclose a personal narrative about my own emotional extremes as context. In publicly displayed writing, I described long standing feelings of emotional distance from others and how, from out of this general state of alienation, I eventually had exploded with reckless emotional abandon. I wrote about these cathartic revolts as catastrophes for my health, connecting my difficulties managing loneliness with the expression of symptoms diagnosed as bipolar disorder in 2012. This was the first time I ever publicly disclosed my diagnosis in a work of art. I meant to give participants a chance to decide to participate in the project knowing some of the weight of their choice. It never meant forcing other people to disclose their own trauma. In general I found that being direct about framing my own experience, expectations, and boundaries, helped build conditions for others to decide whether or not to participate consentfully. Our meeting one another in improvisation felt potentially full of empathy only due to this consent.

Even so, I would be lying if I said the interactions always felt like my interlocutors were growing in empathy with me as opposed to feelings for me. What did I know of their inner lives? The asymmetry had to do with an imbalance of knowing and feeling. Did I spread empathy at all or just some other less reciprocal pathos? Based on intuitions and voiced feedback from participants, I don’t think this project was just a chamber of pity, but there was something unstable in its design.

Writer and literary critic Namwali Serpell traces patterns of appropriation and saviordom “against the public good” in forms of narrative art that promote empathy building as a discrete goal. By encouraging audiences to feel the suffering of some subject or community, Serpell claims artists often distract from the immediacy of their urgent suffering, giving rise instead to solipsistic inner cyclings in the empathizer, unintentional convolutions of sensation and righteous indignation in which emotional extremes never metastasize in a substantial form of social action. Empathy becomes synonymous with an oblivious, moralizing liberalism, forgetful of its own positionality, privilege, and responsibility. Storytelling for the sake of empathy in this way can cover over the work of justice rather than reinforcing it. Justice and good art, in Serpell’s analysis, require redistributing the means of storytelling equitably through self- and community-led practices of aesthetic representation that dismantle asymmetries.

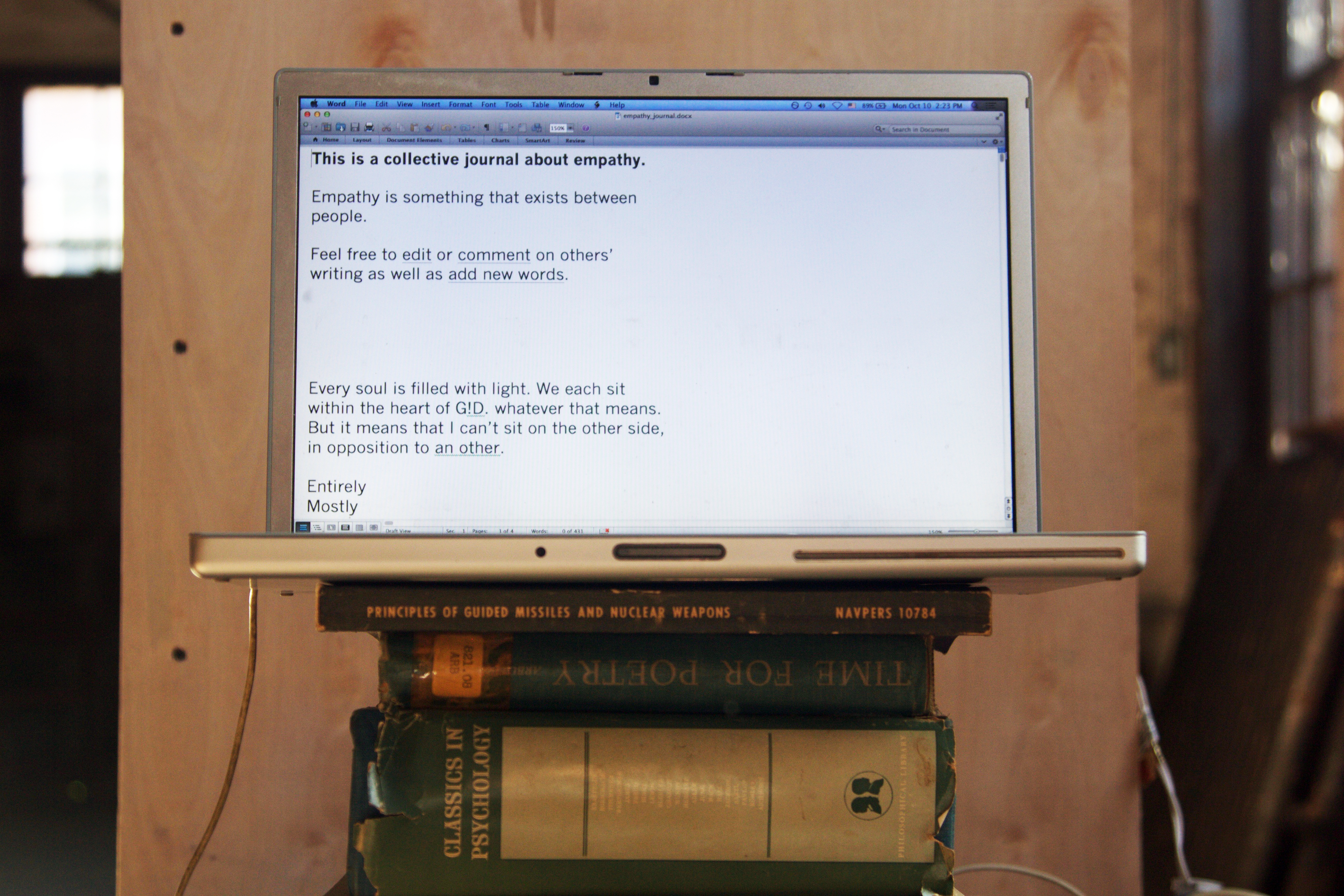

Music improvisation can be just as asymmetrical as reading some author’s printed composition off a page. I would do The Empathy Chamber differently today, designing the experience to more transparently unpack power dynamics built into the facilitation of empathy building. I should mention here that I set up a collective journal about empathy at the 2016 event to stoke participant feedback and critical narrative production. Expanding this practice might be another way to respond to Serpell’s critique of empathetic asymmetries.

2.

Realigning power dynamics could also come from reconsidering the second assumption above: (2) we should build empathy: it is good and right.

I come from a family of bleeding heart liberals whose immediate response to the question ‘should we be more empathetic?’ is a resounding yes always. My sister and cousins and I were socialized to value universal empathy, the belief that one should always have empathy for everyone else they meet at all times under any circumstances. (This value is a part of the built world I inhabit. One co-working space I recently passed through had a sign sharing core values, beginning with “Be Empathetic.”)

Susan Lanzoni explores the roots of this moral imperative and other related ethical doctrines of empathy, drawing them to a time after World War II and the Holocaust when empathy stopped being a fringe academic term describing phenomena of aesthetics, instead metamorphosing into a mainstream fixture of social psychology and popular political discourse. Sarah Sentilles connects this value shift to the moral philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas, who formulated an ethical first philosophy based on the phenomenon of encountering the other.

Hanna Rosen and Alix Spigel’s recent Invisibilia podcast ‘The End of Empathy’ explores challenges to universal empathy in today’s post-Me Too, Trump Era interpersonal landscapes. The podcast considers two conflicting media portrayals of an abuser. In one version, the subject is approached with radical, unconditional empathy, but this universal empathy for the abuser is shown to frame him as a victim, detracting from the lived experiences of his actual victims. Vying for the priority of the abuser’s experience, marginalized experiences are deprioritized, giving a sort of authority and license to the abuser.

A second, revised portrayal of the abuser emerges in which his myopia is never allowed to stand on its own, and audiences are kept at a dispassionate, critical distance from his experience. The podcasters use the term selective empathy to describe empathy activated only situationally, circumstantially, often assigned strategically to attend to people in greatest or most urgent need of attention, rather than, say, perceived enemies. There is no resolution at the end of the podcast: Rosen and Spigel reflect on dangers in both universal and selective empathy. The former obviously can do harm to marginalized people. The latter, they fear, may push people to feel only for others just like them, reinforcing tribalism and endangering the multiperspectival fabric of civil society and liberal democracy.

The Empathy Chamber stayed close to universal empathy, blowing past why and how the requirement of empathy can be materially harmful. Seeking to bring interdependence to light, I turned to building empathy indiscriminately. Selective empathy would have inverted this model. Building empathy selectively (according to need, equitably, etc.) would have been a response to what participants and I already knew about our interdependence (i.e., our asymmetries of power). Then we might have set to the work of changing those imbalances. I would have needed more knowledge about my participants’ needs. In a new version of The Empathy Chamber, I would seek this mutual knowing within specific communities in which relationships are already complexly developed and opportunities for growth are more collectively shared. I imagine a space for improvisations between groups of providers and recipients of health care services or peers seeking solidarity with recipients of the same form of care, engaged in the same collective grief, and so on.

3.

My friend a.a wrote me on social media a few weeks ago, voicing a fundamental problem I was having with everything I was reading about empathy:

i suspect that such a thing [as empathy] is deeply impossible for me, in many ways. and I think we often make light, to our detriment, of the ways we are irreconcilably different, unable to share experiences, unable to feel for each other. so I’m very interested in the question “how can we be more just without depending on empathy?”

‘Empathy’ is living a meteoric life as a verbal technology, blistered by the winds of its own multiplicity. Only a century or so old, ‘empathy’ now has at least eight distinct uses, according to social psychologist C. Daniel Batson:

[1] Knowing another’s thoughts and feelings;

Lanzoni, “A Short History of Empathy”

[2] Imagining another’s thoughts and feelings;

[3] Adopting the posture of another;

[4] Actually feeling as another does;

[5] Imagining how one would feel or think in another’s place;

[6] Feeling distress at another’s suffering;

[7] Feeling for another’s suffering, sometimes called pity or compassion; and

[8] Projecting oneself into another’s situation.

Many words have more than eight meanings and don’t cause so much trouble. Between [1] and [2] there is the difference between reading and writing; [3] evokes taking sides as if of an argument (cognition) while [4] depicts achieving direct symmetry of emotion (feeling); [2] and [5] involve the difference between an emotion and a thought experiment; [6] and [7] approach sympathy; and [8] concerns fantasy. (I might add [9]: A capacity or personality trait allowing one to perform actions [1-8].)

In this maze of interlocking phenomena, social psychology offers notions of emotional empathy (“I feel your pain”) and cognitive empathy (“I can imagine what you are going through”) in hopes to disambiguate empathy’s meanings. I’d respond that I have never had a thought without being in some or other emotional state. We all can feel the feeling of having no feeling, even in states of flatness, disinterest, distraction, dispassion, and the like: all of which are still what social psychologists (and many philosophers) habitually conjure when imagining ‘pure thinking.’ Part of why phenomena 1-8 above bleed so ridiculously into one another is that each phenomenon challenges the thinking-feeling binary, calling out a different potential action, some corner of direct contact, symmetry, sharing or else outright co-option, even pure fabulation. Empathy remains cumbersome in this maze of intention. It is designed to do too much.

4.

Someone showed me care at the end of The Empathy Chamber without depending on the language of empathy. On the last night of the show in 2016, I was approached by AB, a stranger I did not recognize from the improvisations in the chamber. They offered to pass me a zine and cassette mix in response to my writing. Weeks later we met. I was honored to receive the gifts in their home. AB’s writing was about imagining emotions as weather patterns that flow over entire communities and are hosted through us in a sort of ecology of affect falling like rain. With words like ‘expression,’ ‘containment,’ ‘control,’ ‘connecting,’ and ‘feeling’ (but not ‘empathy’) they invited readers to consider the flow of emotional presence, power, and openings to justice:

When I sit there with you I feel how your loneliness empties you and wanders, but also I feel my loneliness and the loneliness between us and its not that I

understand your experience,

or even that I am

holding these feelings for you

it’s that the air is lonely and through my different body I’m

breathing it

and

you.

-AB, T∞B

AB’s gift invited me to not “make light” of our mutual irreconcilability while still acknowledging how we sometimes exceed ourselves to connect with one another across boundaries (passing as if out of us, through our breath: recalling the family of words respire, inspire, spirit, etc.). Leslie Jamieson calls such border crossing an act of “expatriation.”

The Creative Resilience Collective, a health justice community group I co-organize in Philadelphia, will soon announce It’s Not Always Sunny, an anti-stigma campaign challenging happiness as a ‘normal’ or ‘healthy’ feeling, an assumption built into traditional mental health care services. We are carving space for the fullness of Philadelphia’s feelings to be felt, expressed, and cared for without a normativity of affect demanding orderly, plastic versions of contentment from our communities. (If you are a Philadelphia-based reader interested in learning more and/or participating, please get in touch.) The Empathy Chamber may re-emerge as part of It’s Not Always Sunny, delineating space for communities to explore emotional weather patterns with collective intention. This project is directly inspired (to the root of the word) by AB’s gesture and writing.

5.

Across the stories of Going There there are dual currents of hurt and hope. My inner landscape is equally complex. We all need strategies to challenge the socialization of distance and bad myths of invulnerability that are holding us back from radical strength and peace. I dedicate this space to the stories of my co-creators, both in this room and elsewhere: behind us, beneath us: in ancestral territories. Let’s keep an open ear.

-The Empathy Chamber (2016)

The last recorded duet on The Empathy Chamber cassette tape (starting at 18:02) is not an improvisation with a stranger. It’s the sound of my mother and I sitting down in The Empathy Chamber after the rest of the crowd had cleared out on the last night of the show. I realized at the time (could it be?) that this would be our first time ever improvising music together. Gone was the tabula rasa of the stranger: I sat across from my own mother’s smile, her manicured fingers ready to touch sound. Mom’s expression became serious as I set up. Maybe we were both thinking about the weather patterns within our family and what (spiritual-emotional-intellectual) gear we use to brave storms. I wondered about parts of Mom’s experience I couldn’t access. She must have been thinking about Dad, considering when it would be appropriate to say, “Your father would be proud of you.” I wanted to meet her in this labor of grief and show her that I felt her care. We donned headphones. I pressed record. I remember smiling mostly, enraptured by Mom’s slow, patient, full gestures. It was totally unlike how I thought it would go. She later revealed to me she had taken piano lessons as a child. As someone who studies aural genealogies intergenerationally, I was amazed to learn something so fundamental about my mother’s relationship with sound through The Empathy Chamber.

It is certainly lucky to have a mother who is unashamed of my loneliness, grief, and madness, unafraid to be found emoting in public along with the fullness of my feelings. Mom raised me to express empathy with Sicilian hand gestures that knock over wine glasses. Politically, I think our family’s brand of overflowing feelings has given us to a form of universal empathy that could and should evolve into something more selective, less fearful of the nuanced forms of care that are possible at a distance. Still, it is from my present position of emotional inheritance that I can engage in the work of transforming empathy at all. I would not trade it for some other.

Aesthetic practice brings us to encounter living and dead antecedents in ways traditional history or journalism can’t. Through The Empathy Chamber, I came to know Mom better as a living ancestor. I also consider my own past selves. Who I was when [x]… is someone other to me now. Through the veil of the past, I am meeting the version of me who facilitated The Empathy Chamber in 2016, selectively expending my present empathy to reach toward a different time, uncovering notes for a transformative ethics of remembering and forgetting in this passing moment. What would be the work of grief without such self-empathy? A question for future empathy chambers.

Bennett Kuhn is a musician-in-residence for Synapsis for the ‘18-’19 academic year. His music and critical writings engage spaces of care medicalized or otherwise across topics of mental illness, ALS, chronic kidney disease of unknown causes and birthing, dreaming, and grief. Follow Kuhn’s music and writings on Instagram, Soundcloud, and Twitter (@RADIOKUHN).

Thanks to readers and sounding boards a.a, Kimya Imani Jackson, Jesse Kohn, Kyle Halle-Erby, Dianne Loftis, Andrea Ngan, Austin America, Sterling Johnson, Chris Rogers, Christian Hayden, L’Oréal Porcéia, Lee Clarke, Paul Baisley, Joan Barnett, and Elizabeth Weinstein. Acknowledging the cast and crew of Going There: Elizabeth Weinstein, Keys, Dani Gershkoff, Sterling Duns, Corey Mark, C. Kennedy, Joey Hartmann-Dow, Carl Hoblitzell, and Marty Gottlieb-Hollis, as well as strangers who improvised on the above recordings. Thank you AB for the weather, a.a for clarity, Donna Simonetti for her music. Post artwork incorporates illustrations by Paul Baisley. Photography by Jenna Spitz and Paige Kuhn.

Bibliography

AB, “T∞B.” Self-published, 2016.

Bloom, Paul. “How Empathy Makes People More Violent.” The Atlantic, September 25, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2015/09/the-violence-of-empathy/407155/.

Brown, Sherronda J., and Lara Witt. “White People Don’t Feel Empathy For People Of Color And Here Is Why That Matters.” Wear Your Voice, December 13, 2018. https://wearyourvoicemag.com/race/white-people-empathy/.

Derrida, Jacques, and Anne Dufourmantelle. Of Hospitality. Translated by Rachel Bowlby. 1 edition. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2000.

Hromas, Chris. “On the Relationship of Ethics to Moral Law: The Possibility of Nonviolence in Levinas’s Ethics,” n.d., 11.

Jamieson, Leslie. “The Empathy Exams.” Believer Magazine, February 1, 2014. https://believermag.com/the-empathy-exams/.

Lanzoni, Susan. “A Short History of Empathy.” The Atlantic. Accessed March 30, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/a-short-history-of-empathy/409912/.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Ethics and Infinity: Conversations with Philippe Nemo. Translated by Richard A. Cohen. 1st edition. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1995.

Serpell, Namwali. “The Banality of Empathy.” The New York Review of Books (blog), March 2, 2019. https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/03/02/the-banality-of-empathy/.

Sentilles, Sarah. “We’re Going to Need More Than Empathy.” Literary Hub (blog), July 6, 2017. https://lithub.com/were-going-to-need-more-than-empathy/.

Witchalls, Clint. “Why a Lack of Empathy Is the Root of All Evil” The Independent. Accessed March 24, 2019. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/features/why-a-lack-of-empathy-is-the-root-of-all-evil-6279239.html.