Diana Novaceanu // With the Wellcome Collection hosting the “Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery” exhibit this autumn, the public is presented with works dealing with the medicalized body and its reclamation. Both artists manage to disrupt the male gaze and the medical gaze. For British photographer, activist and writer Jo Spence (1934- 1992) her personal struggle with cancer quickly became a “metaphor for all struggle” (Pieroni et al, 37). As Victoria Foster states, there is “no body in contemporary art that is not sexed, gendered, raced, or oriented relative to class, nationality, and health” (Foster, 3). Spence’s praxis places center-stage a middle-aged working class female body that is visibly marked by illness and medical interventions.

Spence preferred to style herself as a “cultural sniper” (Pieroni et al, 1) rather than an artist. She used cliché, mundane settings to delve into issues of class, power and gender that she considered deeply etched into the fabric of British society. The photographer engaged in collaborative projects with fringe art groups, such as the Hackney Flashers Collective. Spence also organized workshops intended to make an empowering use of this medium “accessible to the people” (Bell, 11). Diagnosed with breast cancer in 1982, the artist was determined to become the subject of her own creative investigation and an active agent in her medical interactions.

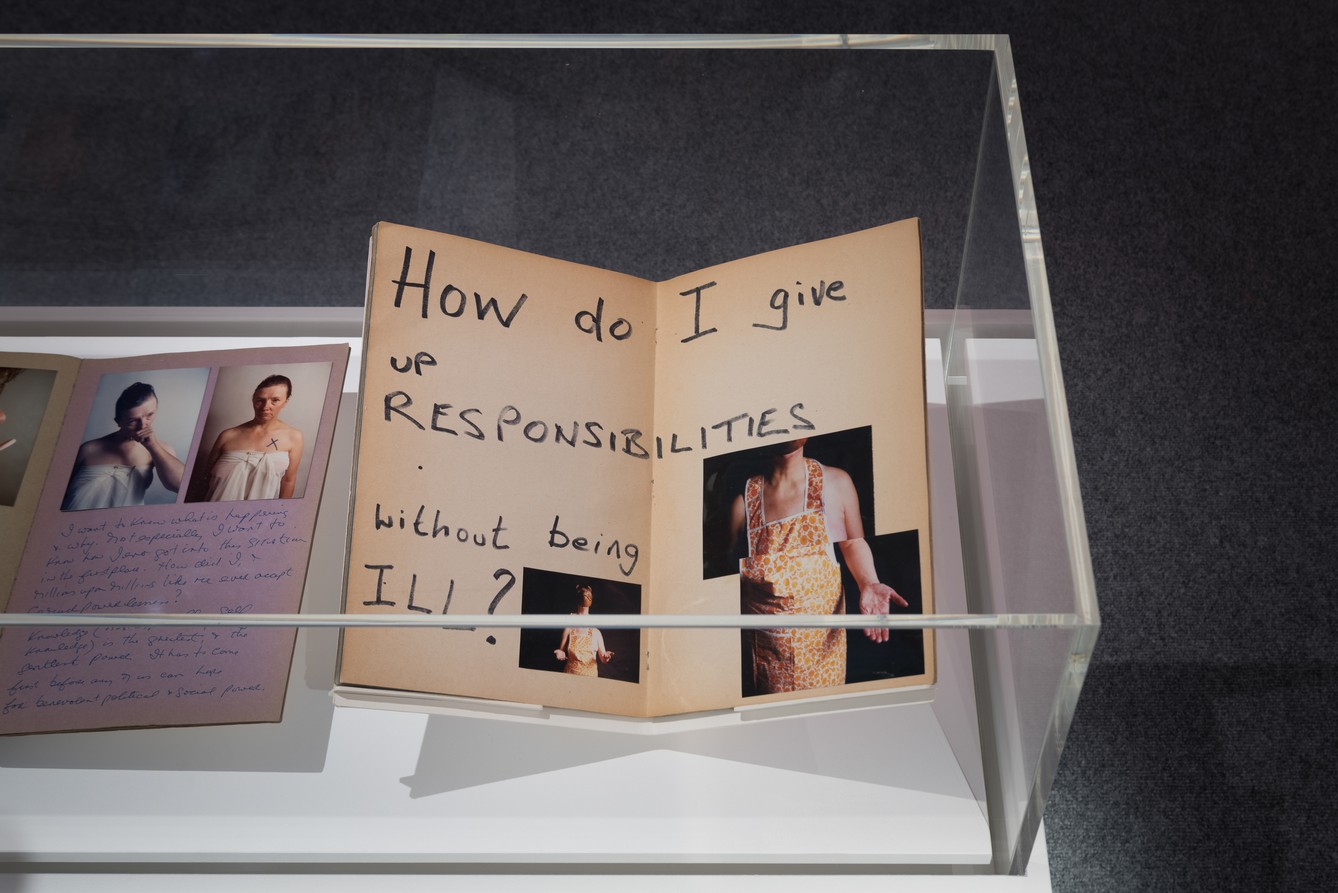

Following her pronouncement, the artist began to amass a body of work that was both biographical and highly experimental. She crafted albums and scrapbooks that served as visual diaries of her illness and treatment approaches. These translated into a series of self portraits and photographic montages belonging to the series The Picture of Health? (1982-1986) and the photo novel Cancer Shock (1982). Later on, she developed along with artist Rosy Martin the practice of reenactment photo-therapy. This was used to work through feelings such as that of being infantilized by the medical establishment. After being diagnosed with a second, terminal, cancer the artist embarked on The Final Project (1991-1992) that included allegorical takes on mortality and its material manifestations.

In the memoir, Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography (1986), Spence recalls a white-coated physician arriving at her bedside, flanked by his student retinue. After glancing over case notes, he proceeds to draw a cross over her left breast. This seemingly ritualistic act of public marking is followed by what, rather than a diagnosis, appears to be a verdict: CANCER.* The breast would have to be removed, it would undergo resection, be permanently separated from the body, in an attempt to isolate the pathologic growth. She describes the initial emotional response: “Equally I heard myself answer, ‘No’. Incredulously; rebelliously; suddenly; angrily; attackingly; pathetically; alone; in total ignorance” (Spence, 150-152).

This clinical encounter left the artist struggling to accept that her body, which she had already begun to reveal nude in explorations of working class domesticity, “was not made of photographic paper, nor was it an image, or an idea, or a psychic structure… it was made of blood, bones and tissue” (Spence, 150-152). The artist mirrors this crucial moment in a photograph entitled How do I Begin? (1982-1983) that sets the staging of The Picture of Health? series. In this self portrait, Spence depicts herself against a stark background, resembling the sterile, utilitarian clinical space. Her cover-up is reminiscent of a hospital gown, or a surgical drape sheet, foreshadowing the upcoming operation. The viewer’s gaze meets her own but is soon distracted by a cross drawn over her breast. In another photograph, the medical marking is replaced by a hand scribbling that questions its’ status as a “Property of Jo Spence”?

This interrogation of body ownership and agency upholds and refines the artist’s ethos. A lifelong socialist, she sought to agitate and push back against what she saw as dire issues affecting the proletariat and described her initial health-centered series as ‘a research project on the politics of cancer’ (Spence, 152). She channeled her consternation at the lack of available patient support into producing work that depicted “the struggle for becoming well” (Pieroni et al, 37), tackling the issue of women taking control not only of their therapeutic journey (which included challenging authority figures such as doctors) but contesting power imbalances on a grander scale. Spence expressed her wishes for an alternate medical paradigm, defined by “less consumerism, more medical accountability, more social responsibility, more self responsibility” (Spence, 152).

Alan Radley examines the need to understand illness in terms of the patient’s own interpretation, taking into account “the individuality of its onset, the course of its progress and the potential of the treatment for the condition” (Radley, 1). Radley calls for an emphasis upon biographical understanding, which for Spence highlights the amalgamation of her artistic and political self. Photography becomes a tool to confront how “ways of being well and of bearing illness are instances and embodiments of ideology and social practice” (Radley, 3). Spence’s body of work develops into what curator Jorge Ribalta aptly describes as “a space for aesthetic-political experimentation” (Ribalta). The artist’s explorations of patient identity diverge from other visual narratives of the time. She elected, after personal research, to undergo a lumpectomy rather than the conventional full mastectomy recommended by her physicians (Dennett, 234). Rejecting chemotherapy and anti-depressant medication, she opted for a regimen of complementary and alternative practices, aspects of which were captured in her work.

Spence could not, however, elude what Susan Sontag, herself having underwent treatment for breast cancer, described as “trappings of metaphor” (Sontag, 5). Being diagnosed with leukemia brought an almost inevitable “crisis of representation” (Pieroni et al, 30) as it was “almost impossible to represent” (Pieroni et al, 30). The aesthetic depictions of body fragmentation, the use of transparency and opacity visually mirror Sontag’s premises and will be further explored in a following article.

*I chose to use upper case letters to convey the effect the diagnosis, as well as the way it was delivered had on Spence.

The exhibit ‘Misbehaving Bodies: Jo Spence and Oreet Ashery’ will run until the 26th of January 2020 at the Wellcome Centre in London. A large selection of photographs are may be found online, as part of the Hyman Collection (http://www.britishphotography.org/news/1946/jo-spence-photographs-from-the-jo-spence-memorial-archive) and the Richard Saltoun Gallery archives. (https://www.richardsaltoun.com/artists/36-jo-spence/works/)

A collection of materials relating to her life and works may be consulted by request at the Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive hosted by Birkbeck, University of London.

Header Image: Wellcome Collection.

Works Cited:

Bell, Susan E. (2002). “Photo Images: Jo Spence’s Narratives of Living with Illness.” Health, vol. 6, no. 1. pp. 5-30.

Dennett, Terry. (2011). “Jo Spence’s Auto-Therapeutic Survival Strategies.” Health, vol. 15, no. 3. pp. 223–239.

Foster, Victoria. (2016). Arts Based Research for Social Justice. Oxon: Routledge.

Pieroni, Paul et al. (2012). Jo Spence: Work (Part 1&2). London: Camden Press.

Ribalta, Jorge. (2005). “Jo Spence Beyond the Perfect Image. Photography, Subjectivity, Antagonism”. Spain: Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona.

Sontag, Susan. (1978). Illness as a Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Spence, Jo. (1986). Putting Myself in the Picture: A Political, Personal and Photographic Autobiography. London: Camden Press.