Jessica M. E. Kirwan // I have been pondering the necessity and implications of retrospectively redeeming a procedure that in its own day’s standards was considered highly problematic.

A recent study by researchers at Dokkyo Medical University in Japan, published in History of Psychiatry, reviews 36 nineteenth century cases of Battey’s operation for the treatment of hysteria. Returning to the original findings, the investigators identified potential historical cases of oophorectomy that suggest neurological symptoms caused by a condition now associated with ovarian cysts. Recently it was found that “[a]nti-NMDAR encephalitis patients have various psychiatric and neurological symptoms, and female patients often have ovarian teratomas” (Komagamine). Owing to similarities in the clinico-pathogenesis of hystero-epilepsy and anti-NMDAR encephalitis, the authors asked whether some of the cases of women treated with Battey’s operation during the latter nineteenth and early twentieth centuries may have had symptoms suggestive of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, for which today women are screened for ovarian masses. And, yes, according to these authors’ findings, in three of these patients the ovaries “appeared to have ‘cystic degeneration’” suggestive of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, and all three patients fared favorably after the procedure (Komagamine).

If you don’t know what Battey’s operation is, you’re not alone. Known today as an oophorectomy, Battey’s operation was the standard terminology during the late nineteenth century for resection of the non-cystic ovary. The procedure developed intercontinentally but was popularized by American gynecologist Robert Battey after he performed his first oophorectomy in 1872 and reported on its efficacy in a woman whom he had failed to relieve of pain after five years under his care. Battey and his patient believed the treatment worked. This was one of various cases he published.

The justification for its use related to tenuous theories about the function of the ovaries. Battey came to believe that bringing on the “change of life,” or menopause, would relieve women of conditions and diseases caused by an irregular reproductive system. At this time, it was still not entirely clear that any activity by the ovaries induced menstruation, but it was believed that the ovaries were a catalyst to menstruation. As Laqueur explains in Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud, “when Battey and [colleagues] began removing healthy ovaries, and at the height of popular belief in the life-determining role of the organ, almost nothing was known for its function in women and no effort had been made to exploit what little veterinary experience existed,” of which there were some studies indicating that the ovaries were central to menstruation, and exhibiting the various changes in the body that resulted from their resection.

In its early days, the procedure was considered highly dangerous. Battey himself reported an overall mortality rate of 18% in 1881; this mortality rate had risen from 13.5% in his 1880 summary of 15 cases in the British Medical Journal. Battey reported 2 deaths among 15 women. Of the 13 surviving women, 2 additional women did not experience any improvement while the rest were still “improving,” “comfortable,” “good,” or in “perfect health.” In this 1880 summary, Battey provided indications for the operation, arguing for its wide usage. He wrote,

“The writer foresaw from the first that this operation could not be laid down as the remedy for any particular disease or class of diseases; while, upon the other hand, in certain exceptional cases, the range of its applicability must be widely extended to a variety of diseased conditions. When asked, is it applicable to this disease or that disease? He found himself forced to answer both No and Yes. To escape this dilemma, he formulated the following proposition. It is indicated in the case of any grave disease which is either dangerous to life or destructive to health and happiness, which is incurable by other and less radical means, and which we may reasonably expect to remove by the arrest of ovulation or change of life.”

His later results presented to the Medical Association of Georgia in 1886 showed improvements in the technique as evidenced through a lower mortality rate.

Dr. James Marion Sims, in 1877, provided a description of Battey’s operation for the Royal College of Surgeons of England, reprinted from the British Medical Journal, in which “conclusions were arrived at by the careful study of a single case.” Owing to this experience, he advocated for the removal of both ovaries in every case to bring on “the change of life.” He admitted that cure rates were low at first but was hopeful for improvements. In his summary of 28 cases, 5 had resulted in death. Nevertheless, he advocates for its use in cases of “prolonged physical and mental suffering attended with great nervous and vascular excitement,” “insanity,” and “epilepsy.”

Dr. Wiliam H. Baker condemned the practice in an 1885 article in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, arguing that it caused “a great deal of suffering” owing to its “unwarrantable” use in “cases where no such serious treatment was necessitated.” In “The Use and Abuse of Battey’s and Tait’s Operations,” Baker cautioned against the quick adoption of new techniques simply because of excitement over something novel. One of Baker’s main concerns was infertility: “when we remember by its successful performance, we forever cut her off from child-bearing, I am sure the wiser and more cautious gynaecologist will reserve this method of treatment for extreme cases.”

By the end of the nineteenth century, this radical procedure had become synecdoche for surgeon over-reach in women’s healthcare. The procedure was overly prescribed for various physical and psychological conditions despite the lack of evidence to its efficacy. During the height of its popularity, only few “large” series and mostly case reports had been published. One of the main arguments against its use in England was the concern that it made potentially fertile women infertile.

As Moscucci explains, “Oophorectomy was not as prevalent in Britain as it was in America. Most gynaecologists objected to the operation because they believed that it induced not only sterility, but also the loss of sexual feelings and the assumption of the masculine characteristics. At a time of fears about the decline of the race, labour unrest and feminist agitation, the ‘unsexing’ of women was focused on as a threat to marriage and the sexual division of labour, the two pillars on which the stability of society and the supremacy of the British nation rested.”

Highly ardent in his disapproval was Thomas Spencer Wells, Britain’s most renowned ovariotomist, who in 1891, at the height of its use, published his lecture, “Modern Abdominal Surgery” with an “Appendix on the Castration of Women.” In this lecture, he referred to Battey’s operation as “[u]nnecessary mutilation of young women” performed by surgeons with “loose professional morality” whom he believed discredited the profession. Wells, as other physicians, felt it was their responsibility to protect patients from misinformation and that a patient suffering from a mental illness was especially unsuited to make such a serious decision for herself. He also suggested that Battey’s positive results could be attributable to the recovery from the procedure rather than to a cure to the original illness.

But many of the reasons in opposition to the procedure were as unscientifically sound as reasons in favor, or perhaps morally driven rather than scientifically driven. Wells’ main concern, for example, was that the surgeon performing Battey’s operation was violating an ethical responsibility: “mutilation for the sake of terminable maladies (which are the fruits of a vicious civilization or a reckless procreation) is rather a question for the moralist than the surgeon,” he argued. To refer to the procedure as castration was a bold statement, but even more bold was his claim that the “oophorectomists of civilization touch hands with the aboriginal spayers of New Zealand.” To perform Battey’s operation, Wells argued, meant to sever an entire family lineage and, therefore, to defy God’s intentions. “Reproduction is the dominant function of woman’s life, and all her other living actions are but contributory,” he stated. Women were simply built differently, he believed, and, as such, “have more sensibility…[and] a tendency to…diseases of an aesthetic character.” These natural facts, he believed, were God’s will and not to be tampered with. Ironically, however, as Laqueur states, “removing the ovaries also made a woman more womanly, or at least more like what the operation’s proponents thought women ought to be. Extirpating the female organs exorcised the organic demons of unladylike behavior.”

In his excellent 1979 review of the nineteenth century literature on Battey’s operation, “The Rise and Fall of Battey’s Operation: A Fashion in Surgery,” Lawrence D. Longo describes some of these women who went to Battey for treatment of mental and physical suffering which they believed was related to their menstruation. When reading the symptoms these patients presented with, it is undeniable they were suffering. It would be naïve of us to assume that the women who underwent these operations were forced into them. Nancy Theriot’s research in the early ‘90s showed, in fact, that many women chose medical treatments that today we consider radical and unrelated to the health issues they sought to address.

In her article, “Women’s Voices in Nineteenth‐Century Medical Discourse: A Step toward Deconstructing Science,” Theriot discusses the active participation of women in the medicalization of many woman-specific conditions. In her review of nineteenth century medical records, she found that “women came to physicians asking to be committed or to be given medication for behavior the patients themselves described as insane or nervous, including lack of interest in husband and family, violent feelings toward their children, and continual sadness or suicidal urges in spite of being well taken care of by husband or family…In addition, however, husbands were bringing wives, and mothers bringing daughters, for unwomanly behavior. Such traits were linked to the concept of insanity or nervousness.” She continues, “Women most often related their illness to their female bodies, sometimes linking them to child birth, menstruation, or other reproductive issues, believing the uterus responsible and ovaries were responsible…In general, these medical records indicate that women perceived their reproductive lives as troublesome.” In her article, “Negotiating illness: Doctors, patients, and families in the nineteenth century,” Theriot shows “evidence of women patients in dialogue with their doctors treating themselves as manageable bodies separate from their families.” Doctors’ opinions were centered on patients’ sense of wellness and illness. Women themselves sought out medical attention by these physicians. They knew from other women what health concerns to address. While today we are tempted to vilify Battey and his knife-happy colleagues, we would be disregarding the agency of the women who electively underwent these procedures. But, as Longo points out, the problem with Battey’s surgery is that its indications were never clearly defined and, as Wells argued, women were not always properly informed of the outcomes of this treatment.

Over a brief period, advocates and opponents debated the usefulness of the procedure, and, compared to their male colleagues, the few women physicians in practice at the time were reluctant to either advocate for or strongly oppose its use. In general, radical procedures such as Battey’s operation were viewed negatively by feminists; therefore, the women physicians who performed this and similar procedures did not necessarily vocalize or publish their cases. An exception is Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell who was known to criticize Dr. Elizabeth Garret Anderson for excessively using surgery on women, and she spoke against the oophorectomy in her text, Essays in Medical Sociology (1902; London: Ernest Bell).

In Catriona Blake’s history on women physicians, Charge of the Parasols, she explains that when the New Hospital for Women was opened in 1872 Anderson performed various surgical procedures, including Battey’s operation, which led Dr. Frances Hoggan to resign her post at the hospital. “The [hospital] committee insisted that the operation be conducted elsewhere for fear of the reputation of the hospital being damaged if it failed,” explains Blake. Anderson performed surgeries at a private off-site location instead. “For 20 years she was the only woman on staff who could perform major surgery.”

Also interesting, “At the Birmingham Medical Hospital for Women, Louisa Atkins and Eliza Walker trained under Robert Lawson Tait, who had four other women working under him in the 1870s at a time when most hospitals refused to employ women doctors. He was strongly opposed to animal vivisection. He was also, however, a major proponent of experimental surgery techniques in gynaecology such as ovariotomy” (Blake).

In 1906 Van De Warker estimated that around 150,000 women had undergone an oophorectomy since 1872. The recent aim of the researchers at Dokkyo Medical University was “to elucidate whether patients with characteristics suggestive of anti-NMDAR encephalitis received Battey’s operation when it was first being performed.” The authors found that, yes, some of the patients who received the operation may have suffered from anti-NMDAR encephalitis. In addition, the authors discuss cases exhibiting symptoms of neurological conditions that today are still believed somehow associated with ovarian function, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome-associated depression, anxiety, and epilepsy. Of the historical cases, 63% had evidence of cysts or cystic degeneration. The authors recognize the limitations of their study and the potential biases of studying only those women who underwent Battey’s operation; they also highlight the ambiguity of the historical diagnosis of hystero-epilepsy. Moreover, pathologic review was not common at the time, and physicians greatly relied on patient testimonials to determine whether a procedure was necessary or successful. Nevertheless, the authors succeed in describing the historical evolution of our understanding of the function of the ovaries. In a sense, though, as they acknowledge, their findings are somewhat incidental in that many women with these symptoms did not undergo Battey’s operation, and many cases of women who did were not described in the literature.

Hindsight will sometimes justify a historical procedure. Longo argues that, however misguided, Battey’s operation helped advance our understanding of pelvic surgery and ovarian function; however, as Laqueuer argues, animal studies at the time could have illuminated gynecology’s understanding of the ovaries without having to perform the operation on women, had physicians not willfully ignored these studies. I also wonder whether, owing to the anti-vivisection movement, which was especially strong among women and feminists, veterinary studies were dismissed or purposely ignored. Furthermore, the debate was one centered around an ideal of femininity that many feminists found problematic. In returning to my original question, why even revisit this procedure? While it is interesting to parse out whether the nineteenth century prescription for Battey’s operation was productive in any sense, ultimately, the inherent limitations of the historical archive obfuscate its usefulness in contributing to the kind of empirical scientific knowledge we rely on today, such as large cohort studies. That said, historical studies such as these help elucidate the archive of data available on this historical procedure, which contributes to our historical record and our contemporary understanding of surgical trends. Future research in this direction could help illuminate the role women doctors played in this debate as well as patients’ contributions to treatment decision-making.

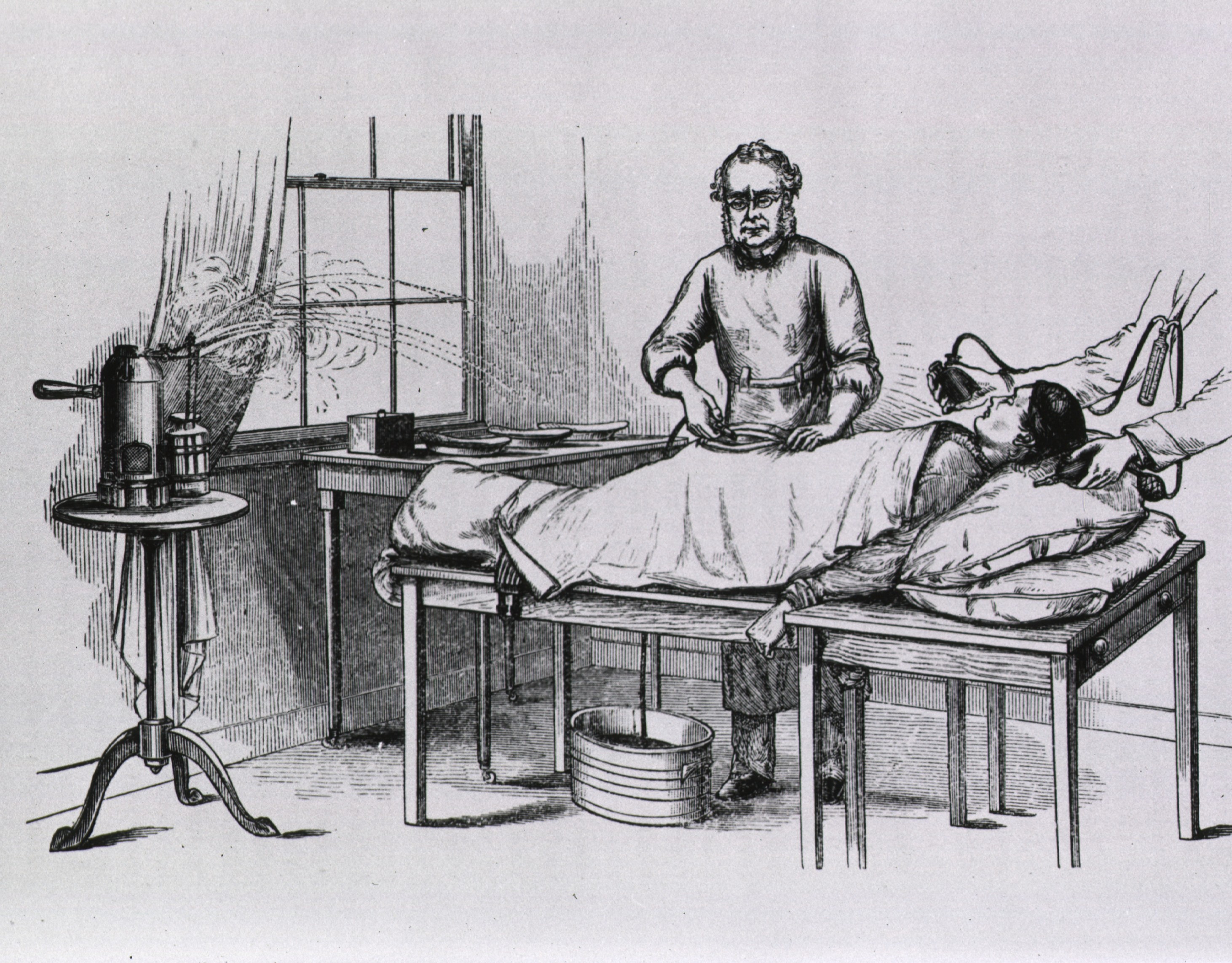

Featured Image: Ephraim McDowell and assistants perform first ovariotomy in America. Public Domain, via The National Library of Medicine

References

Baker WH. The Use and Abuse of Battey’s and Tait’s Operations. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 1885. 150-151.

Battey R. Summary of the Results of Fifteen Cases of Battey’s Operation. British medical Jouranl. April 3, 1880. 510-511.

Battey R. Antisepsis in ovariotomy and Battey’s operation: seventy consecutive cases with sixty-eight recoveries and two deaths. Georgia Medical Association. 1886. Available at http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101283854

Blake, C. The Charge of the Parasols: Women’s Entry to the Medical Profession. London, Women’s Press, 1990.

Komagamine T, Kokubun N, Hirata K. Battey’s operation as a treatment for hysteria: a review of a series of cases in the nineteenth century. Hist Psychiatry. 2019:957154X19877145. doi: 10.1177/0957154X19877145. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 31538814.

Laqueur, T. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1990.

Theriot, N. Women’s Voices in Nineteenth‐Century Medical Discourse: A Step toward Deconstructing Science. 1993. Signs;19:1–31.

Theriot N. Negotiating illness: Doctors, patients, and families in the nineteenth century.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 2001. 37:349–368.

Wells, TS. Modern Abdominal Surgery: The Bradshaw Lecture Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England; With an Appendix on the Castration of Women. London, J. A. Churchill, 1891.

Sims JM. Remarks on Battey’s operation. 1877. British Medical Journal; 2:793-794

Longo LD. The rise and fall of Battey’s operation: a fashion in surgery. 1979. Bulletin of the History of Medicine; 20:244-267.

Moscucci, O. The Science of Woman: Gynaecology and Gender in England, 1800-1929. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Van De Warker E. The fetich of the ovary. 1906. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Diseases of Women & Childbirth; 54:366-373