Sarah L. Berry // If you’re a female voter, thank a woman doctor.

Without 19th-century female physicians, we might not soon be celebrating the 100th anniversary of suffrage. In 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to earn a Doctor of Medicine degree just as the women’s rights movement kicked off in Seneca Falls, NY. Over the next seventy years, organizers demanded political, social, and economic equality between the sexes while at the same time, more and more women entered medicine. Organizing in earlier movements such as temperance and abolition (see Part 1) provided women with political awareness and a literal platform in lecture halls and churches from which to address the public. Speaking for a cause and lecturing on health were equally pivotal to women entering political debate on their own behalf, a social current that soon placed women healers on the front lines of the struggle for full participation as U.S. citizens. This post discusses medicine, both academic and alternative, not only as the first profession for women but also as the driving force behind gaining full citizenship, including the right to vote in 1920.

Heart Histories

It’s not surprising that of the learned professions available to men in the nineteenth century— theology, law, and medicine—women entered medicine first. Women had always been nurses and doctors. As midwives, herbalists, and undertakers, colonial women tended to their families and communities until academically trained male doctors pushed them out around the turn of the nineteenth century.[i] Before Dr. Blackwell made academic medical history, many women had made careers out of healing work. Harriot Kezia Hunt, for example, had studied health and hygiene privately. Although denied admission to Harvard Medical College in 1847, she practiced for forty years, caring especially for working and impoverished women and their children, and pioneering “heart histories,” an early version of patient-centered treatment that made the physician a listener and the patient a participant in treatment. She augmented her somatic therapeutics by repairing emotional bonds, especially between mothers and daughters.[ii]

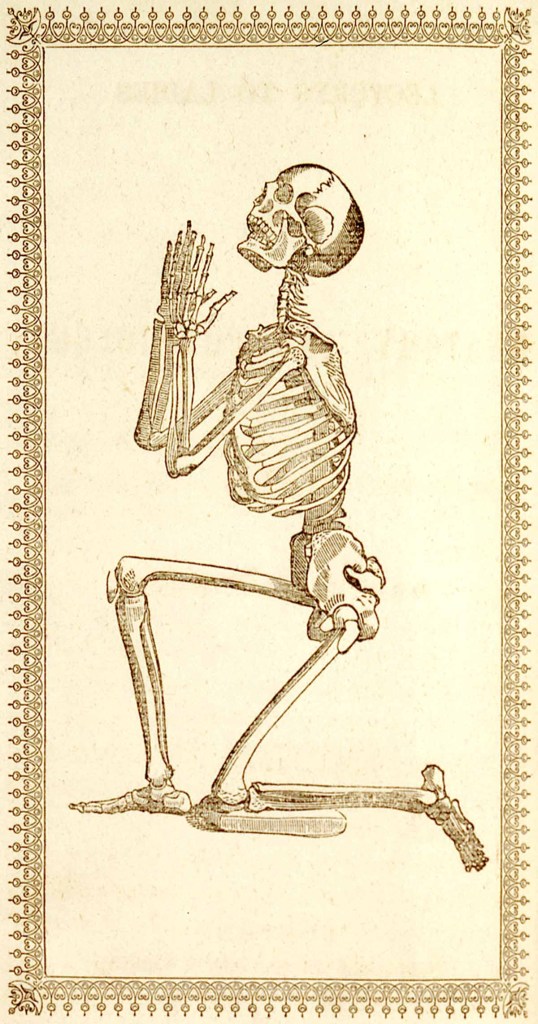

Women drew authority also from their family caretaker experiences. The rigid separation of male and female roles in Victorian America paradoxically lent propriety to educating other women about their bodies and their children’s health. The self-taught Mary S. Gove filled large halls with audiences eager to learn anatomy and physiology. Gove’s Lectures to Ladies (1842; frontispiece with praying skeleton pictured above) surveyed medical literature and advocated diet and hygiene especially to prevent illness in women. She recommended a vegetarian diet to calm nerves and bathing the whole body to wash away “waste and hurtful particles, that would otherwise fester in the system, and cause disease.”[iii] Gove built on her expertise and became a famous water cure physician, developing a treatment system of bathing, wet compresses, and water-drinking along with healthy diet. She founded her own hospital, school, and health journal, and controversially advocated women’s rights to consent to and enjoy sex—a form of autonomy she believed would promote women’s health.

“A great deal that women could do”

Without temperance and abolition reform, there may have been a different outcome for gender-based equality. Women reformers leveraged their perceived purity as females to make change on moral grounds. But abolition also literally sparked the women’s rights movement. Elizabeth Cady Stanton hit a glass ceiling at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840, where she was barred from speaking despite her equal contributions to the cause. Stanton had received a full education,[iv] reserved for boys, from her lawyer father in Boston before landing in rural Seneca Falls, NY and witnessing how average women lived in a constant cycle of pregnancy and childcare, enduring legal wife-beating and scrambling to make ends meet. She took a page from the antislavery playbook and strategically altered the Declaration of Independence to show its hypocrisy—this time, in keeping women subjected to men. In this manifesto, she keenly observed that a married woman was, in the eyes of the law, “civilly dead”—without autonomy, without the ability to transact business, keep her own wages, or even her own name; in short, a living corpse.

Stanton and other abolitionists gathered 300 women and men in Seneca Falls in July 1848 and read to the crowd a list of “injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman,” among them collegiate education and “avenues to wealth and distinction” such as in theology, medicine, and law. Stanton was unaware that medicine was about to change women’s rights forever.

Twelve miles down the road that summer, another abolitionist, Elizabeth Blackwell, was enrolled at Geneva Medical College. She graduated in January 1849 as the first woman to earn the Doctor of Medicine degree. In her autobiography,[v] Blackwell chronicled her struggle to gain the respect of her professors and classmates and to open her own practice in New York City amid prejudice against lady doctors. She completed residencies in Paris and England because she was barred from them in the U.S. She, too, lectured on health and anatomy to women. After opening the first clinic and pharmacy for poor women, she hired women doctors and founded her own medical school. She pioneered academic medicine as a career for women, taking the first professorship. In doing so, she opened higher education to women. Her double achievement of practicing academic medicine and teaching in medicine began to turn the tide of what Stanton had identified as women’s exclusion from the professions and higher education.

Medical colleges for women sprang up around the U.S. from 1850 onward. The first African American woman physician, Rebecca Lee Crumpler, graduated in 1864 from the New England Female Medical College in Boston; after the Civil War, some colleges began admitting women and African Americans. In addition, medical colleges founded for African Americans (HBCUs) increased the number of African American physicians. The total number of women physicians increased from 200 in 1860 to more than 7,000 in 1900.[vi]

Women continued working for political equality until the nineteenth amendment gave women the federal right to vote in 1920. After the Civil War, lady doctor stories became popular. One in particular, “A Day with Dr. Sarah” (1878) by Rebecca Harding Davis,[vii] captures the political clout of women physicians near the end of the century. Davis’s heroine must decide whether to take in orphaned children or lobby Congress in Washington, D.C. Women physicians were pioneers in “moral [sex] education,” industrial health and safety, obstetrics, gynecology, pediatrics, and public health. They served communities from urban immigrant neighborhoods to rural farm towns, proving that women could be professionals and citizens as well as mothers and daughters. Ultimately, their status and cultural authority helped persuade men to ratify the nineteenth amendment.

[i] See the diaries of Martha Ballard in Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812. New York: Vintage, 1991.

[ii] Burbick, Joan. Healing the Republic: The Language of Health and the Culture of Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century America. Cambridge, 1994. pp. 182-83.

[iii] Gove, Mary S. Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology. Boston: Saxton and Peirce, 1842, p. 174.

[iv] At this time, middle class women typically received a second-grade education.

[v] Blackwell, Elizabeth. Pioneer Work in Opening the Profession to Women. [1910]. Reprint edition, Humanity Books, 2005. Blackwell’s autobiography was published at the end of her very long life, and just a decade before women won the vote in 1920. In this context, its emphasis on the political gain of professional equality for women) are key. Professional advancement in medicine remedies some of the deprivations identified by Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1848.

[vi] Clark Hine, Darlene. “Co-Laborers in the Work of the Lord: Nineteenth-Century Black Women Physicians.” In “Send Us a Lady Physician”: Women Doctors in America, 1835-1920. Ruth J. Abram, ed. W.W. Norton, 1985. pp. 108-109.

[vii] Davis, Rebecca Harding. “A Day with Dr. Sarah.” In A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: Life in the Iron-Mills, Selected Fiction, and Essays. Edited by Jean Pfaelzer. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996, pp. 317–328.

Featured Image: Wood Engraving from Mary S. Gove’s Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology (1842), Public Domain, via National Library of Medicine