Madeleine Mant // 2020 is the year of the mask. Whether manufacturing, stockpiling, MacGyvering, sewing, 3D printing, or debating them, masks are (figuratively, if not literally) on everyone’s lips. The efficacy and culture of masks as personal protective equipment has been investigated for over a century’s worth of diseases, including the 1910-’11 Manchurian plague (Lynteris), influenza (Chuang; Cowling), SARS (Sin; Syed), tuberculosis (Biscotto), and Ebola (MacIntyre et al.). The spike in face-mask purchasing and crafting in response to COVID-19 fears is not surprising. Anxiety over invisible invaders encourages individuals to desire a barrier, to wrest back a feeling of control. Anthropologists have explored the imagery of disease-repelling face masks as “potent symbols of existential risk” (Lynteris 442), while Lasco explains that motivations including “cultural values, perceptions of control, social pressure, civic duty, family concerns, self-expression, beliefs about public institutions, and even politics” might make an individual cover their face.

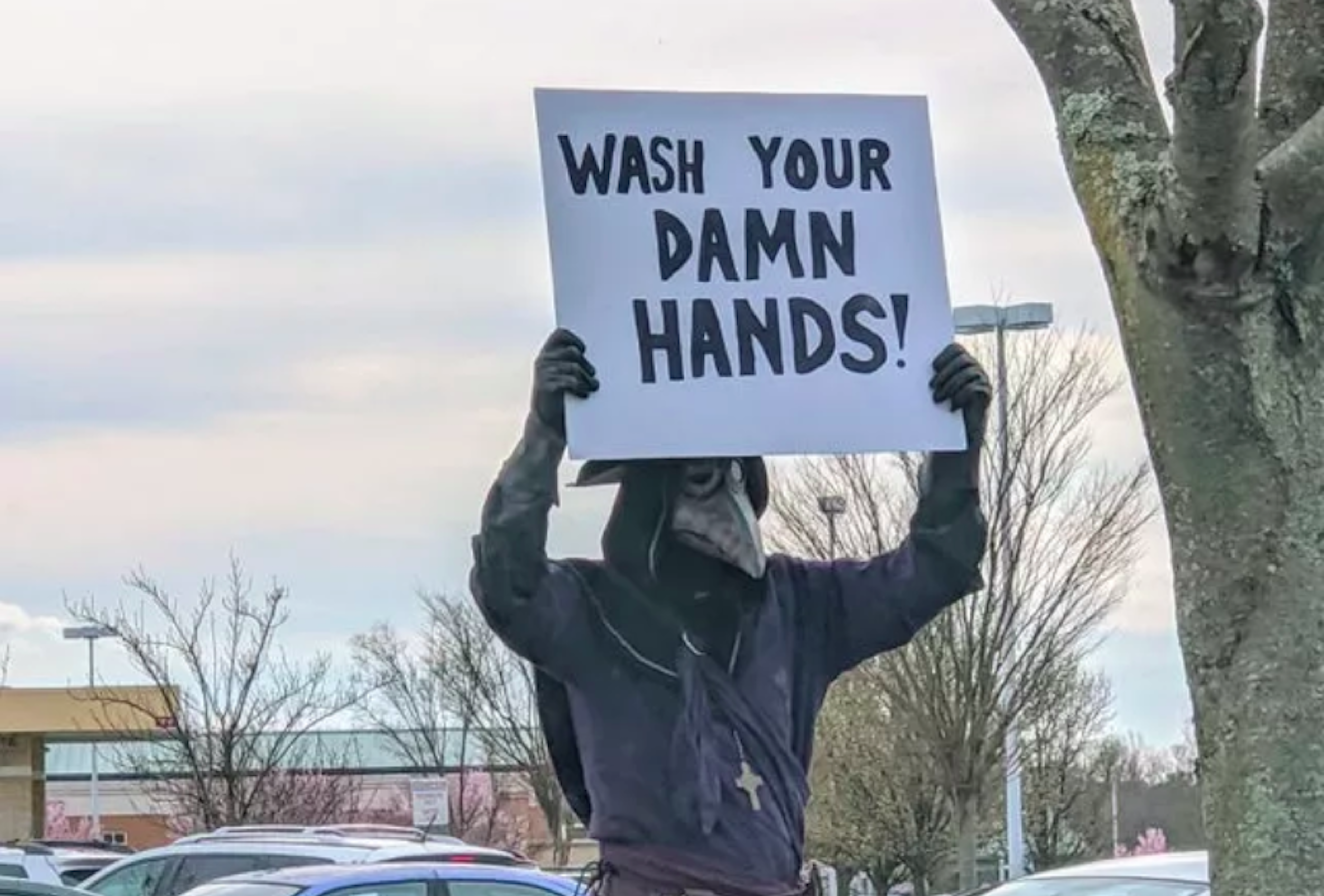

Steeped in our current context, the stage was set for the Plague Doctor, that iconic masked medical icon, to make a comeback. Memes predicting Spring 2020 fashion replete with black capes, canes, and beaked masks flooded social media in March 2020, as the rapidly increasing number of COVID-19 cases made global headlines (Figure 1). Folks in beaked masks wandered onto live on-location newscasts. TikTok stars like Dr. Miasma (@plaguetimes) reminded a rapt online audience to wash their hands. Using props gathered for teaching undergraduate anthropology courses on infectious disease, and being an extrovert trapped in social distancing mode, I myself started a daily photo series featuring a Plague Doctor encouraging creative pursuits and self-care while self-isolating. The organic appearance of these media demonstrates the Plague Doctor’s powerful juxtapositions: the image is historical yet current, sinister yet welcome, celebrating life yet embodying death.

Plague became endemic in Europe after the shattering Black Death pandemic of 1347-51, leaving subsequent generations to face the invisible foe intermittently. Physician Giovan Agostino Contardo of Genoa wrote of plague in 1576, “prevention is much more noble and necessary than therapy” (Contardo 5). Beliefs in miasma, that disease was spread by noxious-smelling air released by decaying matter or the foul expulsions from dying humans and animals, meant that a prophylactic and protective outfit to separate the doctors and their patients was a logical step.

Frenchman Charles de l’Orme (1584-1678), court physician of Louis XIII, is credited with inventing the Plague Doctor’s iconic costume in the early 17th century in response to the myriad plague epidemics striking Europe. He described the outfit in the following way:

“The nose [is] half a foot long, shaped like a beak, filled with perfume with only two holes, one on each side near the nostrils, but that can suffice to breathe and carry along with the air one breathes the impression of the [herbs] enclosed further along in the beak. Under the [waxed] coat we wear boots made in Moroccan leather [goat leather] from the front of the breeches in smooth skins that are attached to said boots, and a short-sleeved blouse in smooth skin, the bottom of which is tucked into the breeches. The hat and gloves are also made of the same skin… with spectacles over the eyes” (quoted in Mussap 672-3, his translation and insertions), a description which matches the undated plague mask displayed in Ingolstadt’s German Museum for the History of Medicine (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Undated plague doctor mask from Deutsches Medizinhistorisches Museum (Inv. No. 02/222)

The beak of the Plague Doctor’s mask was stuffed with aromatic herbs to prevent the doctor from inhaling the putrid stench of death and disease (Manget, quoted in Blanchard 589-90) while the glass goggles prevented the miasma from reaching the doctor’s eyes. Canes were employed as a tool for maintaining social and medical distance, a means of examining buboes, feeling a patient’s pulse, and perhaps a potential weapon for keeping desperate patients at bay. The wide-brimmed hat and separate mask more familiar to modern interpretations of the Plague Doctor derive from images such as Figure 3, a 17th-century engraving interpretation from Rome.

During the 1630 plague outbreak in Verona, one physician reported: “During this bad epidemic, following the practice of the French physicians, the town of Lucca made a provision that the plague-doctors ought to wear a long robe of thin, waxed cloth. The robe had to be hooded and the doctors had to visit the patients with the head covered and wearing spectacles” (Pona 30). This costume was so popular in Italy during plague outbreaks in 1630-31 and 1656-7 that contemporary medical writers (Paul Fürst in Germany (1656) and Dr. Manger in Geneva (1721)) described it as an Italian medical costume, ignoring its French origins (Cipolla, “Fighting” 11). Other doctors wore robes made of toile-cirée, linen cloth coated with wax (Salzmann 5-14). Stretchers used to carry the sick to pesthouses in 1630 Florence were covered with waxed cloth (Catellacci 384) and doctor’s carriages were similarly covered with waxed cloth during the 1656 outbreak in Rome (Savio 117). It was thought that smooth waxed surfaces would not allow the miasma to stick; furs, feathers, and woollens were to be avoided with the assumption that the foul vapours would more easily be caught up in their surfaces.

If the doctors’ costumes and precautions were successful in protecting them from plague, it was because the outfits were repelling fleas, not miasma (Cipolla, “Fighting” 12). Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative coccobacillus easily spread by rat fleas, was at this point hundreds of years from being identified or understood. The invisible foes—bacteria, viruses, parasites—continue to co-exist with and haunt humans today. While infectious diseases have increasingly “come into view” due to technological advancements and better understandings of animal and environmental vectors, the reality remains that without enhancement, we cannot view our microscopic invaders with a naked eye. We can, however, view the manifest symptoms and sufferings of the victims as well as the increasingly important symbol: the mask.

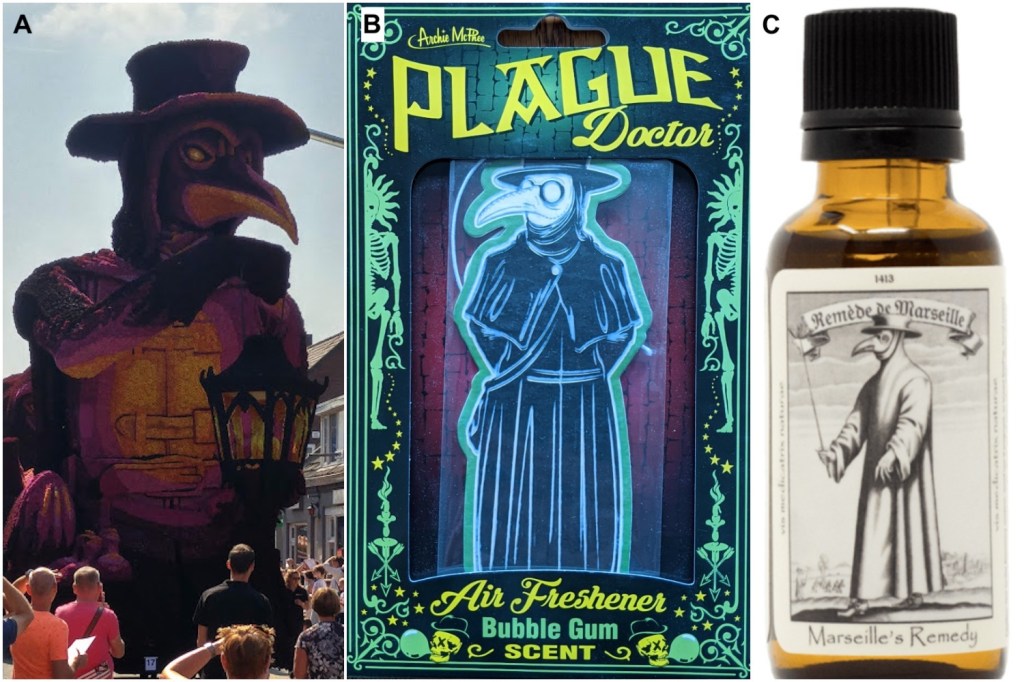

Plague Doctors easily integrated themselves back into cultural consciousness because while Yersinia pestis’s grip on human history was loosened with the advent of antibiotics, the evocative Doctor did not fade. We find the Doctor’s image capitalized upon in television shows, album art, skateboard decorations, plush toys, and, particularly ironically, as air fresheners (Figure 4). Marseille’s Remedy, an essential oils blend, is branded with Fürst’s Plague Doctor. The image is clearly employed to legitimize the products with a sense of medical history and tradition; however, the message is muddied as the 17th-century image of Rome is labelled as 15th-century France. The sombre beaked, cloaked, and hatted figure struts his danse macabre each year in Venice’s carnival as the popular commedia dell’arte figure Il Medico della Peste. Similarly, the doctor was a popular dahlia float at the 2018 Bloemencorso Zundert, touted as the world’s largest flower parade. The character in these contexts is entertaining, but ultimately anodyne – there is little dread associated with encountering the doctor at a modern pageant or dangling from the rear-view mirror. And yet, more contemporary popular cultural appearances of the Plague Doctor have become ever more ominous in nature.

Figure 4: (A) Plague Doctor dahlia float, Bloemencorso Zundert, 2 September 2018 (photo by Madeleine Mant); (B) Plague Doctor Air Freshener, Archie McPhee brand (photo by Madeleine Mant); (C) Marseille’s Remedy®: Traditional Marseille’s Remedy Oil (credit below).

Plague Doctor aesthetic is evocative. Steampunk subculture, though primarily inspired by 19th-century technological achievements, often features Plague Doctor cosplay. Filagreed metallic beaks, goggled eyes echoing diving bell helmets, and Victorian morning coats provide a delightfully anachronistic melange. Plague Doctor appearances tend to peak annually at Hallowe’en, a night of masks and mayhem. In another context the Doctor has been imagined as a mummer, a disguised character who visits neighbours’ homes at Christmas, from the mummering tradition in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, as well as parts of Ireland and the UK. The mask in these cases is doing semiotic work through obscuring the wearer’s identity. Masks “‘work’ by coordinating the iconicity and indexicality of signs of identity” as they are used in “disguising, transforming or displaying identity” (Pollock 581-2). The mask replaces the bearer’s face, creating an inscrutable boundary.

Figure 5: (A) Marty Scurll, a.k.a. The Villain (photo by: Scott Lesh); (B) Junior Plague Doctor Hallowe’en costume (photo by: Sandra Garvie-Lok); (C) Plague Doctor Mummer, St. John’s, Newfoundland (pictured: Dale Jarvis, photo by: Greg Locke).

Wrestler Marty Scurll directly channels the Plague Doctor with his character “The Villain,” sporting beaked masks, wings, and feather-laden coats (Figure 5). Asked about the inspiration for his costume, Scurll admitted “it was just an album cover I saw one day…. It was only supposed to be a one-time thing, I did that entrance … people reacted to it … fans would send me drawings of me in the plague doctor mask,” noting that the strong fan reaction to the outfit drove him to incorporate increasingly elaborate elements. Scurll admits the challenges inherent in supporting the aesthetic: “when I actually wrestle all I wear is a little pair of trunks, but when I pack to travel I’ve got to take the coats, the umbrella, the hat, the mask, everything.” Scurll adopted the costume as a dramatic gimmick to open his matches, but the subtextual connection of the look with villainy is telling.

The Plague Doctor occupies liminal space, navigating another danse macabre between life and death, healing and hunting. The original function of the Doctor’s mask was not to obscure identity, but to protect its wearer. The mask also coded the Doctor as an individual set apart, since those bearing the masks were known to plague-ravaged cities as individuals “hired by an infected town or village in time of an epidemic, who were responsible for the treatment of the plague patients only and had to refrain from intercourse with the rest of the population” (Cipollo, “Doctor” 65). To wear the mask was to accept isolation.

Healers

Pop culture examples of the Plague Doctor navigate the tension between life and death by commonly characterizing the figure as either a healer or a hunter, though the boundaries are sometimes blurry. Video game examples drawing directly from 17th-century engraving images include a non-player Doctor in Assassin’s Creed II from whom medicines can be procured and the Plague Doctor in Darkest Dungeon, outfitted with accoutrements for fighting the plague, including a “Rotgut Censer” inspired by a pomander and “Bloody Herb/Poisoned Herb,” referencing the herbs and spices wielded against miasma (Figure 6). Shovel Knight’s Plague Knight is medicine-adjacent as he uses alchemical science to create explosives. Crash Bazley, the Medical Sergeant in Call of Duty: Black Ops 4, has a skin featuring a hood, beaked mask, and red glass eyes.

Figure 6: (A) Plague Knight (Shovel Knight); (B) Plague Doctor (Darkest Dungeon); (C) Dr. Corvus Dunwich Clemmons (Ephemeral Rift). Image credits below.

Dr. Corvus Dunwich Clemmons (read: CDC), a Plague Doctor character from the Ephemeral Rift YouTube channel, provides ASMR treatments for the viewer, who takes on the role of a patient at the Arkham Sanitarium for Mental Rehabilitation (read: ASMR). The character has various masks, appearing with white, black, and brown beaks, gloves, robe, and either a wide-brimmed hat or black cowl. Clemmons discusses medical treatments and body modifications, while engaging the viewer with tapping, scratching, rustling, and whispering, practising a particular brand of medicine for his ASMR patients. The ASMR sensation raises questions of affect, of the emotional and physical work being done by both patient (viewer) and practitioner (Clemmons) in these exchanges.

Within the healing theme, however, lurks modern hubris. GomerBlog, a medical satirical site, sports the Plague Doctor as their emblem. Ingrid the Plague Doctor has her own comic strip detailing her well-intentioned but leech-heavy attempts at medicine while other comics depict the Doctor discovering the very concept of medical school (Figure 7). In this way, the historical Doctor, armed only with their cane and beakful of herbs, becomes emblematic of all medical quackery. While it is true that Plague Doctors were “normally either second rate doctors who had not been particularly successful in their practice or young doctors trying to establish themselves” (Cipolla, “Doctor” 65), these were individuals who did not flee at the first sign of pestilence, unlike private practitioners who, in most cases, abandoned the cities, and did not treat the disadvantaged even under optimal non-epidemic conditions (Byrne 168). The certification of plague deaths by these doctors provide early datasets for modern understandings of plague (Byrne 170). Archival documents outlining the contracts paid to Plague Doctors reveal their importance in battling disease in European cities, though their task was herculean, as described by William Boghurst in 1665 (60):

“But two or three of the youngest are appointed in plague time to look to thirty or forty thousand sick people, when four or five hundred are too few; and at another time, when there dies but two or three hundred a week, you should have five or six hundred [doctors] hanging after them if they be well lined with white metal [silver]. Tis the rich whose persons are guarded by angels.”

While the Plague Doctors may have been able to provide only minimal care for their patients, robbing the Doctors of their context is presentist mockery.

Figure 7: Twistwood Tales Episode 14 (@ByTwistwood)

Hunters

In contrast to the healing theme, subversive killer Doctors abound in popular culture (Figure 8). The Assassins Creed video game series, in both Brotherhood and Revelations, features playable characters with bladed syringes and taunts such as “Come, let me cure you!” Bloodborne’s Eileen the Crow is a non-player character who sports a ‘raven mantle’ and wooden beaked mask to conceal her face as she hunts players who she perceives to have become consumed by bloodlust. Overwatch’s Reaper (outfitted with a Plague Doctor skin) aims to kill his former comrades to fuel his own desire for revenge. Bloodhound in Apex Legends starts with goggles and a modified gasmask and can achieve a Plague Doctor mask, while the antagonist Whalers of Dishonored sport goggles and mouth-coverings reminiscent of the Plague Doctor. Bird references are clear, with Eileen the Crow’s crowfeather cape, Reaper’s feathery silhouettes, and Bloodhound’s raven familiar emphasizing the aesthetic over the historical roots of the costume. The game worlds involve a dizzying medley of industrial Victorian-era elements, subplots concerning plagues, Lovecraftian and Bram Stoker-inspired imagery, and scattered historical elements. Similarly, the anime series My Hero Academia features Overhaul, a germaphobe intent on healing the world he perceives to be sick. Characters motivated to reveal the “sickness” they perceive in others speak to larger themes of othering, or blaming groups perceived to differ from the norm for existential threats such as pandemics.

Figure 8: (A) The Doctor (Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood); (B) Eileen the Crow (Bloodborne); (C) Overhaul (My Hero Academia); (D) Bloodhound (Apex Legends); (E) Reaper Plague Doctor Skin (Overwatch). Image credits below.

The Plague Doctor figure is invoked in supernatural circumstances as a source of horror. Dark Horse Comics’ Death Head prominently features a masked killer with the tagline, “In the woods they found a mask. At home he’ll find them.” Supernatural’s episode Advanced Thanatology (S13E05) involves the ghost of a killer doctor with a collection of beaked masks. Dan Brown’s protagonist, Robert Langdon, hallucinates a vision of hell replete with Plague Doctors in Inferno. Girl on the Third Floor employs the masks in a pseudo-erotic flashback, a low-budget Eyes Wide Shut. These representations are effective entertainment, playing upon common fears of obscured identities and illness. In these cases, the Plague Doctor is separated from the medical context; the murderous figure could as easily be Jason Voorhees, Ghostface, or Michael Myers.

It appears that the Plague Doctor is here to stay, a historical icon rooted deeply in modern anxieties. We watch the Doctors on the silver screen, build them elaborate backstories in Dungeons and Dragons, and tattoo the beaked visage into our flesh. As a symbol embodying infection or fighting infection, a quack or a brave helping hand, a sinister harbinger of doom or an aesthetic, the Plague Doctor remains complex cultural shorthand. Refracted through the pandemic lens of 2020, the Plague Doctor has become an oddly comforting sight, a moment of anachronistic jocularity in an overwhelming wave of frightening viral panic.

Works Cited:

Boghurst, William. Loimographia: An Account of the Great Plague of London in the Year 1665. AMS Press, 1979.

Biscotto, Cláudia Rocha, et al. “Evaluation of N95 Respirator Use as a Tuberculosis Control Measure in a Resource-Limited Setting.” The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, vol. 9, no. 5, 2005, pp. 545-9.

Blanchard, Raphaël. “Notes Historiques sur la Peste.” Archives de Parasitologie, vol. 3, 1900, pp. 589–643.

Byrne, Joseph. (2006). Daily Life During the Black Death. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006.

Catellacci, Dante. (1897). “Curiosi Ricordi del Contagion di Firenze del 1630.” Archivio Storico Italiano, Serie V, Vol. 20, no. 208, 1897, 379-91.

Chuang, Ying-Chih, et al. “Social Capital and Health-Protective Behavior Intentions in an Influenza Pandemic. PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no. 4, 2015, e0122970.

Cipolla, Carlo M. Fighting the Plague in Seventeeth-Century Italy. University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

Cipolla, Carlo M. (1977). “A Plague Doctor.” The Medieval City, edited by Harry A. Miskimin, David Herlihy, and A.L. Udovitch, Yale University Press, 1977, pp. 65-72.

Contardo, G.A. Il Modo di Preservarsi e Curarsi Dalla Peste. Genoa, 1576.

Cowling, Benjamin J., et al. “Face Masks to Prevent Transmission of Influenza Virus: a Systematic Review.” Epidemiology and Infection, vol. 138, no. 4, 2010, 449-56.

Lasco, Gideon. “Why Face Masks Are Going Viral.” Sapiens, 7 Feb. 2020, www.sapiens.org/culture/coronavirus-mask/. Accessed 14 April 2020.

Lynteris, Christos. “Plague Masks: the Visual Emergence of Anti-Epidemic Personal Protection Equipment.” Medical Anthropology, vol. 37, no. 6, 2018, pp. 442-57.

MacIntyre, Chandini Raina, et al. (2014). “Respiratory Protection for Healthcare Workers Treating Ebola Virus Disease (EVD): Are Facemasks Sufficient to Meet Occupational Health and Safety Obligations? International Journal of Nursing Studies, vol. 51, no. 11, 2014, pp. 1421-6.

Mussap, Christian J. “The Plague Doctor of Venice.” Internal Medicine Journal, vol. 49, 2019, pp. 671-6.

Pollock, Donald. “Masks and the Semiotics of Identity.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 1, no. 3, 1995, pp. 581-97.

Pona, Francesco. Il Gran Contagio di Verona nel 1630. Verona, 1631.

Salzmann, C. “Masques Portés par les Médecins en Temps de Peste.” Aesculape, vol. 22, no. 1, 1932, pp. 5-14.

Savio, Paolo. “Ricerche Sulla Peste di Roma Degli Anni 1656-1657. Archivio della Societá Romana di Storia Patria, vol. 95, 1972, pp. 113-42.

Scurll, Marty. “Marty Scurll sits down with X-Pac!” – Xpac 12360 Ep. #53, 6 Sept. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1673&v=L6FLf6lIWa4&feature=emb_logo. Accessed 14 April 2020.

Sin, Maria Shun Ying. “Masking Fears: SARS and the Politics of Public Health in China.” Critical Public Health, vol. 26, no. 1, 2016, pp. 88-98.

Syed, Qutub, et al. “Behind the Mask. Journey Through an Epidemic: Some Observations of Contrasting Public Health Responses to SARS.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, vol. 57, 2003, pp. 855-6.

Image credit details:

Ingrid the Plague Doctor comic: https://www.webtoons.com/en/challenge/ingrid-the-plague-doctor/list?title_no=329453

GomerBlog: https://gomerblog.com/

Figure 4: Marseille’s Remedy®: Traditional Marseille’s Remedy Oil (https://marseillesremedy.com/product/traditional-oil/)

Figure 5: Marty Scrull image by Scott Lesh (https://twitter.com/ScottLesh724/status/1073856494314102785)

Figure 6: (A) Plague Knight (Shovel Knight)

https://shovelknight.fandom.com/wiki/Plague_Knight

(B) Plague Doctor (Darkest Dungeon) https://darkestdungeon.gamepedia.com/Plague_Doctor

(C) Dr. Corvus Dunwich Clemmons (Ephemeral Rift), screen capture from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4WY_ZLgG-Y

Figure 8: (A) The Doctor (Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood) https://assassinscreed.fandom.com/wiki/Doctor_(Animi_Avatar)?file=Char_doctor.png

(B) Eileen the Crow (Bloodborne) https://vsbattles.fandom.com/wiki/Eileen_the_Crow

(C) Overhaul (My Hero Academia) https://bokunoheroacademia.fandom.com/wiki/Kai_Chisaki

(D) Bloodhound (Apex Legends) https://apexlegends.gamepedia.com/File:Bloodhound.jpg

(E) Reaper Plague Doctor Skin (Overwatch) https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=767348991