Jane C. Desmond //

Have you ever done a CAT scan on a cat?

When we hear the term “medical humanities,” we usually think of humans, but the post-humanist turn in the humanities alerts us that we live and practice in a more-than-human world.[i] Over the next few essays, I’ll share perspectives and provocations for our thinking in the medical humanities that can come from the world of veterinary medicine. How might enlarging the medical humanities to embrace veterinary medicine offer new challenges to our concepts of patient agency, for example, or notions of “consent,” or perhaps the challenges of end-of-life care when euthanasia is a daily possibility in practice?

As a professor of Anthropology with a specialty in American Cultural Studies and human-animal relations, I have, since 2012, spent time conducting fieldwork in veterinary medicine at my home institution’s College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. I’ve conducted participant-observation research in clinics, in operating rooms, in classrooms, on farms, and in anatomy labs, thanks to the generosity of my colleagues there. Subsequently, I was invited to join the affiliate faculty of the College of Veterinary Medicine, serving as the only humanist on the staff.

In this capacity, I teach a key elective for first year vet students—“Contemporary Issues in Veterinary Medicine”—through which I have the opportunity to introduce concepts of social formations—like racialization, social class, gender and sexuality—and their impact on the profession. We also address the politics of access to medical care, and I introduce the tools of narrative medicine and graphic medicine, as well as units on veterinary ethics conducted with practicing vets. This spring, I will co-teach a new elective on “Ethics and Conflict in Zoological Medicine: Hot Topics in Zoo and Wildlife Management” with the head of our Wildlife Clinic, Dr. Samantha Sander, D.V.M., who is board certified in zoological medicine. There we will grapple with notions of our medical obligations to those in our care (captive) or ranging outside of it (wildlife), species-ism, and what “wellness” might ultimately mean.

In a curriculum just as crowded with required/essential courses as human medical training is, these veterinary electives and similar innovations at other vet schools offer a rare opportunity to provide future doctors with conceptual, creative tools to place their practice of medicine in a social and historical context. This, in turn, can foster creative thinking about change as they join the profession and, ultimately, make it their own.

I also serve as a member of our campus-wide Medical Humanities working group and am on the subcommittee there to develop the humanities curriculum for the newly launched Carle-Illinois College of Medicine. Crossing between human medicine and veterinary medicine provides me with a unique perspective, echoing some of the understandings captured in cardiologist Dr. Barbara Natterson-Horowitz’s book (with Kathryn Bowers) titled Zoobiquity: The Astonishing Connection Between Human and Animal Health[ii], which detailed her experiences as an M.D. working with D.V.M.s and rose to the top of the New York Times bestseller list in 2012. Moving across these two arenas of medical training, as when Natterson was called to a zoo to consult on a case, is still rare, but such collaborations offer new potentials, not simply at the bedside or cage-side, and not only in One Health, but more generally in thinking deeply about strategies of care, the politics of access, the challenges of communication, and the mental and emotional stresses facing doctors of all sorts.

Situated at this juncture, I have two goals. The first is to help bring contemporary veterinary medicine into the already well-established medical humanities, to test the illuminating power of the comparison, which invites us to go beyond the practice of translational medicine to rethink our very notion of the “patient.” The second is to bring the power of the medical humanities to the field of veterinary medicine, which just recently formed its first ever global list-serve on the veterinary humanities, uniting vets and humanists in several different countries (veterinary-medicine@googlegroups.com), and hosted, in October 2020, a first virtual conference titled “Veterinary Humanities Network: Doing Animal Health in More-than-Human Worlds.” In Synapsis, I’ll be writing about the former—exploring the potential that thinking about human and animal clinical medicine together might yield for the medical humanities.

From the outside, the structures of medical training, debt burden, residency matches, cancer treatment protocols, high tech imaging, etc. look to be almost the same for both human medicine and for non-human animal medicine in the United States and many other countries, including those Mexico, Australia, Japan, and parts of Europe. (Of course, there is also significant variation around the world.) But from the inside, key differences in structural, ethical, economic, and technological dimensions, as well as social determinants, are in play. By probing these similarities and differences and analyzing their implications, we can explore what such a practical and conceptual enlargement of the purview of the medical humanities might yield.

For now, I’ll leave us with this question, never more timely perhaps than when we now struggle with Covid-19 and the global impact of zoonosis, a zoonotic phenomenon facilitated through a complex network of climate change, cultural dimensions of species relations, loss of habitat, economic disparities, and woefully inadequate notions of animal welfare. What difference can it make to the future of the medical humanities when the patient is a dog? Or a cow? Or a parrot? Or an elephant? Or a pangolin? Or a…?

[i] The broad impact of “post-humanism” across the humanities and humanistic social sciences in the past 15 years or so has resulted in expansive developments in many fields, from literary studies to anthropology and from history to law, a vibrant intellectual landscape that exceeds the bounds of this essay. For just a tiny sample, see Cary Wolfe, What is Posthumanism? (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009); Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

[ii] Barbara Natterson-Horowitz, with Kathryn Bowers. Zoobiquity: The Astonishing Connection Between Human and Animal Health. (New York: Vintage Books, Random House Publishers, 2012).

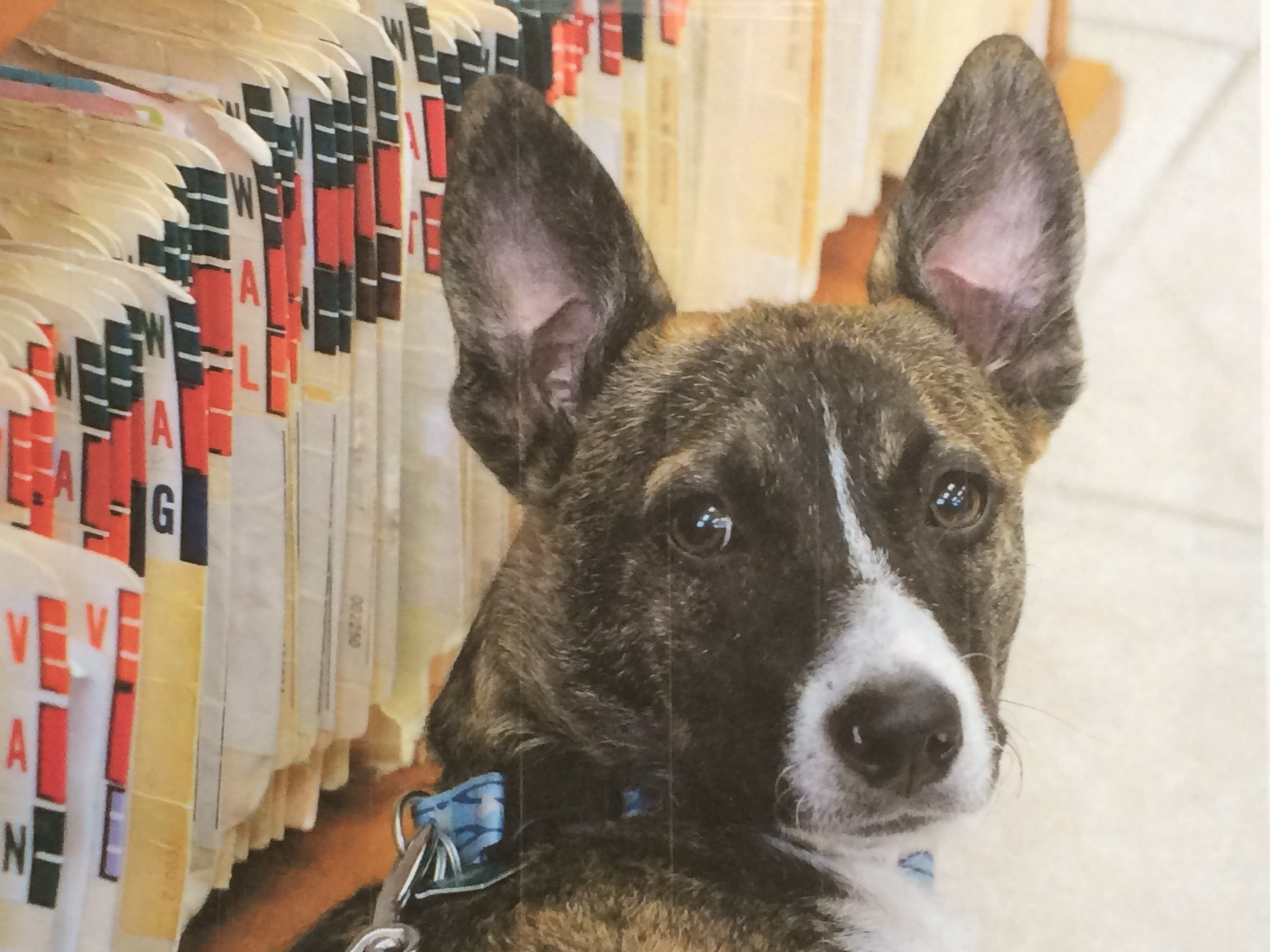

Photo by J. Desmond.