Travis Chi Wing Lau //

It is said that one of the greatest forms of academic love is when a colleague comes across a source, and they write to you to say they thought of you immediately. As someone writing about the histories of vaccine hesitancy and health insecurity, let’s just say lately I’ve been receiving a lot of academic love. And for this, I am immensely grateful, as I try to think seriously about the continuities between the revolutionary time of Edward Jenner’s popularization of vaccination and our present pandemic moment.

But at the same time, I am faced with the double-edged sword of “timeliness.” Every new development is another invitation to reimagine, reshape, reconceptualize this project precisely because of its presentist bent. For those who know me, I have been a staunch defender of strategic presentism both in research and in teaching—an approach that does not simply do history for history’s sake but really considers why that history matters to us in the present. I raise this not to hand-wring performatively about the good problem of “relevance,” but instead to reflect on the strangeness of writing about the actively unfolding present. How do we think, let alone theorize, current events as they evolve faster than we can process? How do we, as bodyminds enmeshed in the speed and immediacy of presentness mediated by ever-quickening forms of media, even have the space to do nuanced thinking about that which feels already belated the moment we attempt to write about it?

This is, of course, nothing new to my colleagues who write on contemporary literature and culture. An easy answer is simply to avoid keeping up at all. Part of the challenge of working on the present is the resignation that you must always be in some ways belated because of the very delayed timelines of academic publishing. As a disabled writer, the very arrhythmias of my bodymind and its incompatibility with academic hyperproductivity have always made my writing feel late or behind (or even redundant). But I have been thinking a lot about how the “event of the day” that so often forms the foundation for a monograph’s introduction or coda feels inevitably late in relation to the relentless hot takes of contemporary journalism and social media-driven news cycles. I will defer to my colleagues for a more thoughtful discussion of the formation of these media ecologies, but I am interested in how the “hot take” has fed into more recent pressures on academics to produce timely scholarship in order to keep up. Has the “blogification” or “newsfeedification” of major news outlets and the turn to new media forms like podcasts and shorter-form public writing created greater anxiety for scholars, especially those in the humanities, to consistently prove their relevance in the face of dwindling material support of their work?

In Elspeth Reeve’s brief history of the hot take, the term “hot take” apparently isn’t even that old: dating back to 2012 and derived from sports journalism, the hot take has become a familiar genre of article, blog post, or tweet (or a hybrid of all of these) that wants to get the first word in responding to an event even if it involves oversimplifying it to a headline or a few polemical paragraphs. The impulse also seems to be a kind of colonization of that topic—a desire to claim it by framing it in a way that then everyone else must replicate to access and intervene in that discourse. While we have expectedly gotten to the level of ironic hot takes and even “cold takes” (again derived from sports predictions), this cultural trend of latching onto the timely has only intensified in academic culture in ways that the COVID-19 crisis has made hypervisible.

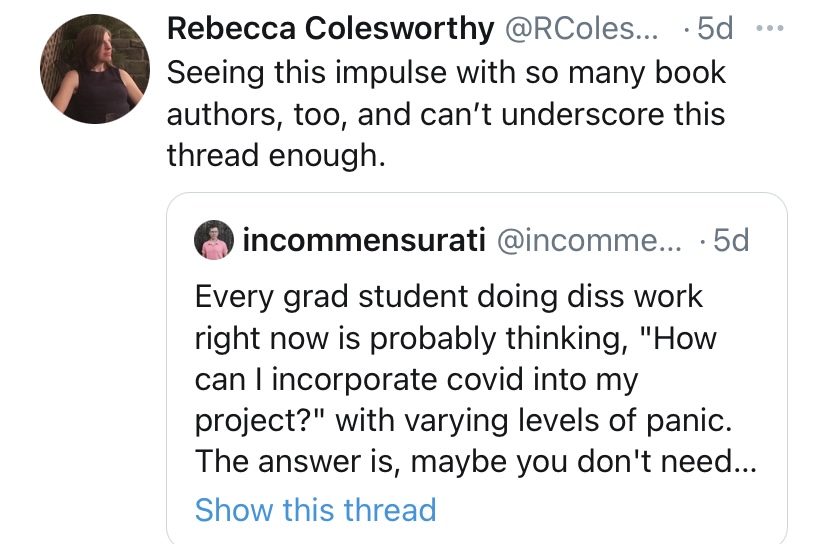

Very recently, I read an insightful thread by a colleague, Aren Aizura, on the mistaken belief that graduate students need to somehow incorporate COVID-19 into their dissertations:

Aren unpacks the way that graduate programs create cultures of pre-professionalization that pressure graduate students into jumping on the next “new thing” when in fact their pre-COVID-19 projects might be better without this heavy-handed link to the present. One of the limits of such pivot to COVID-19 is that its academic impact may in fact fizzle out faster than we may all believe when the vaccine is distributed. This wasted labor of drawing presentist connections for the purposes of relevance takes away from what could be a richly historical project that need not depend on COVID-19 for its stakes to matter. Your take on history might in fact be “the next new thing.”

This exchange reminded me of a recent informational meeting my own department held for undergraduates interested in graduate school. One student asked if they needed to signal in their personal statements a potential project that intervenes in “marketable fields.” Aside from my glib response “what market?”, I understood the student’s concern (even at the undergraduate level) as indicative of just how structural this impulse is to be working on “relevant” topics when the academic job market continues to collapse. With the ongoing loss of tenure lines, rampant adjunctification, and the defunding of humanities departments and programs, choosing a “marketable” field or set of fields feels like bettering your chances with what little agency young scholars have to secure viable employment and, if you’re lucky, tenure. Much like the sudden turn to critical race studies, Black studies, or abolitionist frameworks in the wake of our national reckonings with race relations, making explicit links to COVID-19 has increasingly become an act of strategic branding that underscores the urgency and necessity of a scholar’s work in a publish-or-perish academic culture. I will say this again: this pressure to prove relevance is structural from the level of graduate training to funding opportunities that consistently demand that we justify our work’s value.

Let me be clear: I am entirely guilty of the COVID-19 hot take, which continues to draw racist messages in my emails and DMs. As someone working in a now “trendy” set of interdisciplinary fields—disability studies and health humanities—it is not lost on me that I am often perceived as precisely the kind of scholar relying on the timely to define my career. I am the last person to want to gatekeep the scholarly conversations that are central to my work nor to diminish the great forms of public scholarship that make accessible these conversations beyond the academy. However, I have been deeply troubled by the hypocrisy of scholars who have previously dismissed these fields as “trendy” or “empty” but are now pivoting to COVID-19 for the academic opportunities it presents. Slavoj Žižek, for example, is about to publish a second book on COVID-19. The egregious lack of serious engagement in the scholarship of those who have been doing this work all along aside, I return to my original question: how do we write with any insight about a current event (in this case, a pandemic) when we are very much in the thick of it? Without any spatial, temporal, or personal distance, can we actually talk about the present without being reductively speculative? I ask all of this as I contemplate my own scholarly commitments: if we are to reduce a pandemic that has led to the death of over a million people worldwide to its scholarly urgency, are these commitments even ethical, or have we fallen for the allure of the hot take and its illusory sense of being able to speak substantively to our turbulent present?