Rebecca M. Rosen //

What truly constitutes a person—their consciousness or their anatomy? Who determines “real” personhood, and how much does biological human(oid) anatomy have to do with that? Which is all to say, what is a person, and who can call themselves “real”?

These are the questions viewers are prompted to address in Star Trek: Picard (2020), at least on the surface. But as the series progresses, it turns out that the most recent entry in the franchise is asking even deeper questions about what historian of medicine Katherine Park calls “the secrets of human generation” (Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection, Zone Books: 2006). Framing the late Commander Data (Brent Spiner) of Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94) fame as a kind of ur-android or patriarch to all existing artificial life forms, Picard posits that the greatest act of creation is the birth of new, synthetic human life. Though in his own life he created a child, Lal (Hallie Todd), who did not survive (“The Offspring,” ST:NG, Season 3, Episode 16), in the world of Picard, he is the posthumous father of multitudes. The sense of wonder at his paternity is only compounded by Data’s martyrdom—in the timeline of this show he was destroyed while protecting Picard; thus, his artificial progeny mark a continuation of his existence after death, much as artificially conceived biological children would.

Data’s place in Picard’s pantheon of synthetic life suggests that while artificial humanoid creation is valuable for its own sake, in its ideal form, synthetic creation is an extension of paternal life. In doing so, the show’s first season presents the franchise’s most comprehensive depiction and interrogation of synthetic life and its purpose in the universe, and its vexed view of familial relationships and alliances, whether they are biological, synthetic, or emotional. (Major spoilers for Star Trek: Picard ahead.)

Picard’s first season, created by Akiva Goldsman, Michael Chabon, Kirsten Beyer, and Alex Kurtzman, follows a semi-retired Jean-Luc (Patrick Stewart) as he races across the galaxy in search of a humanoid android, Dr. Soji Asha (Isa Briones). Soji is working as an anthropologist on a reclaimed Borg cube, urging ex-Borg humanoids (called ex-Bs) who have been severed from the Collective to recall their pre-assimilation identities through trauma-informed memory reclamation procedures. Meanwhile, she herself is unaware (at least consciously) of her own essentially fabricated nature, or of the fact that her identical twin being, Dahj, has been exterminated by the Yhat Vash, a secret police force run by the technologically sophisticated but firmly anti-android Romulan Empire.

Picard and others, including Dr. Agnes Jurati (Allison Pill), “the earth’s leading expert on synthetic life,” (S1:E3, “The End is the Beginning,” 40:17), deduce that the two android women—or “synths” as Commander Raffi Musiker (Michelle Hurd) calls them—are the artificial progeny of Data (or, at least, the product of “fractal neuronic cloning” (S1:E1, “Remembrance,” 39:24) of material derived from his remaining cells). Picard, who we learn retired abruptly from his post as admiral after a series of disagreements with Star Fleet over the fate of synthetic and Romulan life (after a seemingly random attack by synthetics on humans on Mars led to a ban on their existence, and the Romulans neared extinction in a supernova, respectively), feels called to action. In sum, Picard, Agnes and Raffi set off in a chartered ship helmed by ex-Star Fleet Captain Cristóbal (Chris) Rios (Santiago Cabrera) to save Soji from harm. Picard’s goals are twofold: to recognize Soji as the offspring of Data and, by preserving her, safeguard the future of synthetic life as an extension of and counterpart to biological existence.

In ST:NG, Data is often portrayed as longing to be human, and as notoriously lacking in verisimilitude. He is a mimetic triumph of humanoid cis-male replication—created by Dr. Nunien Soong (Spiner) as a pseudo-copy of himself, if only in his physical form. But while his contours and frame are fully human, and he has some key abilities that signify him as human-like—including the ability to ingest food and drink—Data’s ghost-white skin and pale yellow eyes announce his status as an “artificial life form,” as do his penchant for rattling off statistics and his constant wakefulness. Data himself is unfazed by questioning stares—“I am an android” he proudly announces to anyone inquiring into his origins—but also freely and frequently discloses his desire to understand humanity, and more closely resemble humans himself. In this paradox—creating a parallel to human(oid) procreation by framing the replication of the father as the basis of all synthetic life—lies the quest at the heart of Picard’s search for Soji, and of Star Trek’s many franchises: a desire to affirm synthetic life as the ideal method of paternal procreation, while affirming personhood as an essentially biological and anatomically legible quality.

Though Data, Dahj and Soji are the most complex examples so far, with the latter two characters unaware of their status as artificially created beings until they encounter Picard, many varieties of synthetic life may be found across the Star Trek universe, ranging from augmented humanity to fully synthetic artificial life forms. The most basic imitation of human life in the franchise is the ship’s incorporeal, aurally present computer (voiced throughout most of its history by Majel Barrett-Roddenberry, partner to series creator Gene Roddenberry), presenting as a disembodied female presence in each iteration of the shows and films. Other beings endemic to the Star Trek franchise mimic humanoid and other species’ physical presence while being essentially immaterial. These are holograms, semi- or fully sentient beings constructed of projected light and matter and who may exist as part of a holodeck simulation, for instructional or emergency purposes, or as semi- or fully autonomous beings. Time and time again, their personhood is assailed, as when the doctor (Robert Picardo) on Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001), originally an emergency medical hologram, becomes a permanent member of the crew, but remains largely shipbound, and without a name.

The most useful examples, for the purposes of this piece, are those beings who are partially or fully synthetic and tangibly three-dimensional. It is their existence and evolution throughout the franchise which prompts viewers to ask what the parameters of humanity are, and whether anatomical fidelity to biological existence, in part or in full, is a requirement of personhood—and, in light of the ban on synthetic life laid out at Picard’s outset, the right to exist.

In the world of Star Trek, synthetic life is framed as evidence of biological augmentation and replication—beginning with instances in which organic beings, primarily human, have bodily augmentations meant to assist or enhance them. These implants and corporeal additions can range from the benign to the malevolent in their form and implementation. The most famous is the visor which Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton) wears on Next Generation. Born blind, the character has optical implants connected to his visor, which give him a unique visual range, different from typical human sight and superior to it in many ways, providing La Forge—an engineer—a unique spectrum of visual information that informs his assessment of structural stability to a degree that surpasses that of other biological beings.

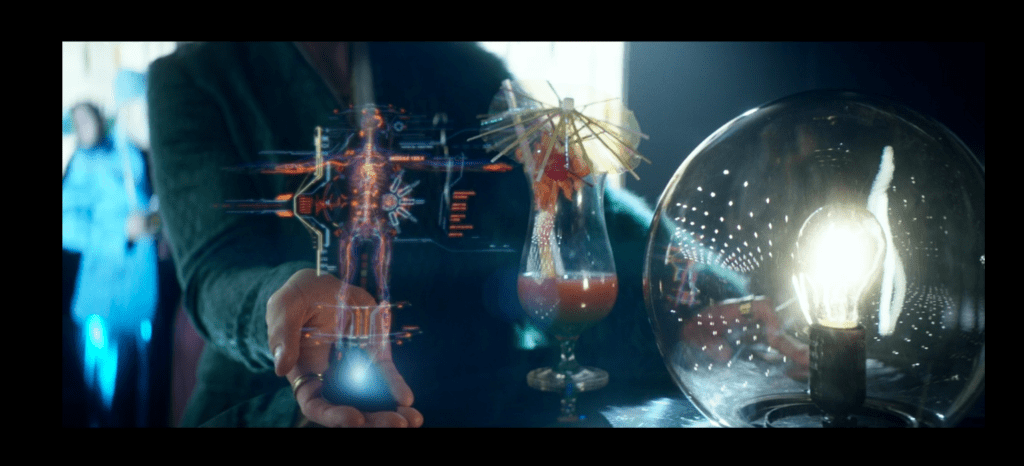

While La Forge’s visor represents an ethical use of cybernetics and prosthetics, on the opposite end of the spectrum are the Borg, who represent the most profound abuse of artificial biological augmentation. Rather than address ability and accessibility, the Borg force their subjects to become technologically augment and linked to each other in the name of efficiency, deindivuated as drones who serve a hive mind. As the experiences of both Picard, who was temporarily made Borg, and Seven of Nine (Jeri Ryan), the ex-Borg who eventually joins Picard’s mission, make clear, being assimilated leaves tangible internal and external anatomical signposts. In a ploy to recover a cybernetics expert being held hostage in episode 5, Seven is used as a decoy to lure the ex-Borg parts trader holding him captive into a negotiation. Having been assimilated as a child, Seven’s biological anatomy and physiology is inextricably bound with technological enhancements and internal regulation systems. When Rios demonstrates this to a buyer, he does so using a series of miniature holographic projections. They resemble nothing so much as anatomical textbook illustrations, with vascular systems and implants supplanting each other in quick succession—reducing a living person to a flap anatomy or static two-dimensional rendering.

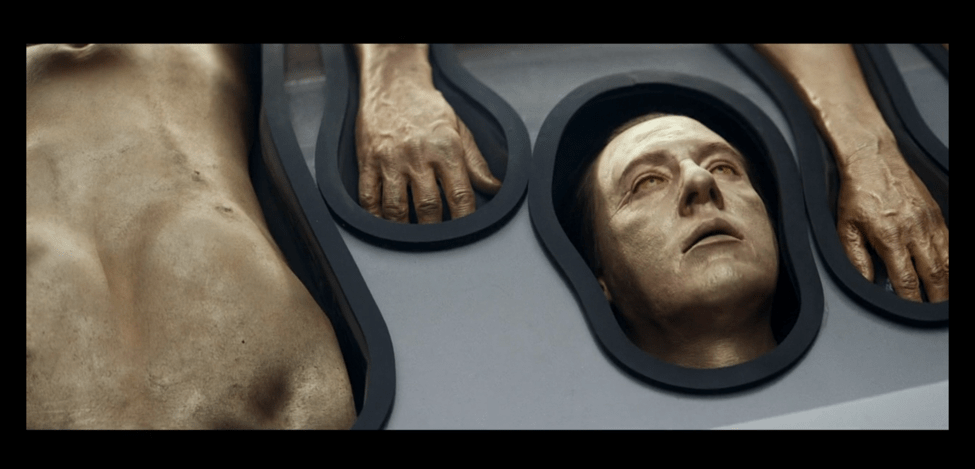

While this encounter is framed as a necessary evil, as it turns out, the high-minded researchers, creators and champions of synthetic life have much in common with the more unsavory residents of Picard’s universe. Both populations invariably view synthetic beings and ex-Borg in similar ways: as collections of parts. Whether through curiosity or covetousness, they each maintain collections of cybernetic parts for research and gain. As Dr. Jurati shows Picard in Episode 1, an early attempt to copy Data—itself meant to produce synthetic “labor units”—lies disassembled in a drawer at the Daystrom Institute.

The disassembled B-4 suggests a cross between the early modern anatomical textbook and curiosity cabinet, a three-dimensional assembly of corpse-like parts (the pallor of the Data-like skin only enhancing this impression). While the effect is somewhat horrific, the essentially jumbled nature of the parts is an assertion of their lack of animacy: like the dissected body, the unassembled B-4 is an inanimate collection of synthetic anatomical remnants. Each piece is outlined and arranged to fit the visual field of the viewer, defying the holistic, much like the hauntingly incorporeal anatomical illustration, in which the living geography of the human body is defied by fitting topographically disparate appendages on the bounded page.

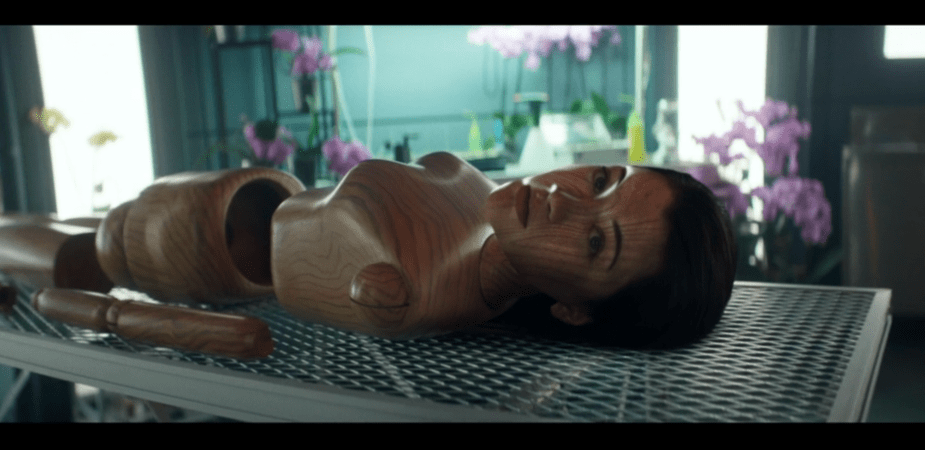

In a parallel vision in episode 6, we see Soji’s primal horror through her eyes, in a recollection that suggests her sublimated self-knowledge: a vision of herself as a disassembled manequin, her personhood reduced to raw contours. In a recovered memory, Soji sees herself reduced to shorthand for a body, like a marionette: a torso, a head, a finial-like pole that suggests an arm, and a hollow interior. The disassembled body lies incomplete against a backdrop of orchids, suggesting biological fidelity, cultivation, and manipulation.

Unlike the B-4, this mannequin’s parts are laid out in anatomical order, like a skeletal model ready for animation (or at least to visually recall it through linear assembly and display). But while the pseudo-Data B-4’s eyes stare into the middle distance from its drawer, this being’s eyes are not only open, but focused. While this is an acknowledgement of Soji’s essentially compromised personhood as a synthetic being, the model’s gaze suggests a challenge. The being that witnesses and assesses its own creation must, inherently, have personhood—even if its anatomical fidelity to humanity is the result of synthesis, one that may be interrupted or undone by human intervention.

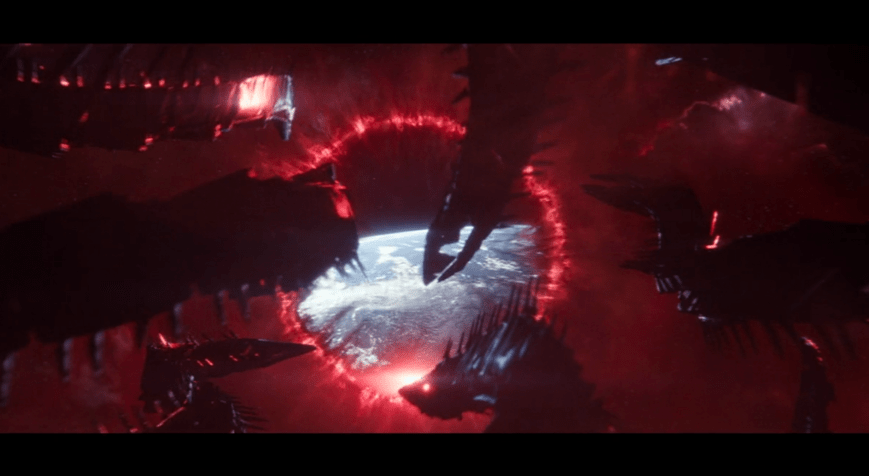

This challenging dynamic prompts an existential threat to human-synthetic relations at the close of Picard’s first season. Each population wonders: can synthetic and organic beings respect each other and coexist, and on what basis? Although Soji is rescued from Romulan threats and brought to her home planet by Picard’s crew, she and her synthetic siblings vacillate between trusting “organics” and desiring permanent liberation from them. Meanwhile, though the Mars attack turns out to have been a Romulan tactic to halt synthetic creation, the Federation and Star Fleet are unsure whether to trust synthetic beings again. And a message which organics and synthetics interpret differently—as either an “admonition” to biological life to fear synthetics, or an invitation from evolved synthetics to their ancestors, calling to end organic life—leads to a standoff in which Soji temporarily builds a beacon that opens a rift in space-time, nearly allowing future synthetics to enter the galaxy and end organic life.

Notably, these beings are not advanced humanoids—they are not humanoid at all. They are serpentine, recalling the intruder of Eden with slithering, unanchored bodies, and no apparent faces—no human family. Soji’s rejection of these beings stems both from Picard’s emotional appeals and the essential non-recognition she feels when she sees them cross the space-time threshold—the opposite of a mirror.

In this way, Picard’s fixation on the paternity and anatomy of Data’s offspring suggests that Soji’s organic and mimetic qualities are resolved because of her human form, and that this resolution may be extended to other humanoid synthetics. Though Data was essentially and tangibly artificial, his offspring appear, as Picard puts it, to be “sentient android[s made] out of flesh and blood.” (“Remembrance,” S1:E1, 36:00-06) While those who fear synthetic life likewise fear the imitation of organic forms, Picard’s conclusion suggests that humanoid imitation—anatomical mimesis—produces not only physical but emotional fidelity, and alignment in the form of a familial relationship. As species, synthetic and organic humanoid beings are similarly vulnerable to destruction—and equally capable of unity and harmony of thought in the face of unfamiliar forms.