Virginia Woolf notes in her essay “On Being Ill”—written from her sick bed in 1925—that the English language has no way to convey disease’s alienating effects to the healthy. Woolf states, “English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet, has no words for the shiver and the headache” (6). Woolf gives the example of a patient with a migraine who cannot gain sympathy from either doctors or his family: the word “headache” is simply not strong enough to explain the affliction’s unceasing electric-like waves or concurrent isolation. To alleviate this limitation of English’s vocabulary, Woolf proposes that writers craft a new language—a more “sensual” and “primal” one —to voice illness (7).

Woolf’s new language exists; it is called “comic books.”

Scholars have written about graphic narratives’ ability to portray disease effectively for some time. In 2014, Kimberly Myers and Michael J. Green gave three reasons why comics craft a new language for illness. First, comics can highlight the visual effects of illnesses on the body (575). Second, comics can juxtapose text and image (574). In their example, from Marisa Marchetto’s graphic novel Cancer Vixen, Marchetto draws herself and her mother staring wide-eyed at a doctor while his speech bubble spits out scribbles with the occasional words—”cancer,” “lumpectomy,” “may not be invasive,” etc. (Marchetto 89). While the clinician speaks, the text below the panel states that the patient will bring a tape recorder to the next session to go over the MD’s talk as many times as she can. Panels like this one can visualize emotional reactions to an illness concurrently with verbal descriptions of that same disease. Third, Myers and Green argue that comics often visibly alter text, and these modifications can show how patients undergoing treatment react to specific words or phrases both verbally and visually (576). The pair argue that these elements of comics can educate medical practitioners on how to empathize with patients more than other art forms because “[t]he use of images with text universalizes the illness experience, facilitating a greater connection with [a] character” (576).

Myers and Green are integral contributors to “graphic medicine,” a field that studies “the intersection between the medium of comics and the discourse of healthcare” (Czerwiec et al. 1). There is an annual conference associated with the subject at which medical doctors, artists, and critics come together to talk about this juncture.

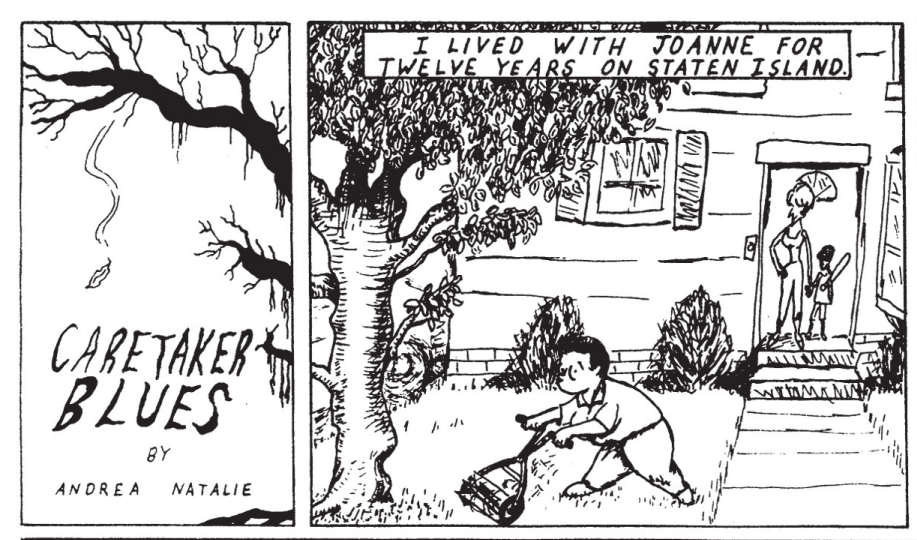

I presented at the most recent conference. My talk was on Andrea Natalie’s “Caretaker Blues” (1992), a comic about a woman named Patty Robbins. Patty suffers from lupus. During the worst stages of the protagonist’s illness, Natalie’s comic does something with its main character that the medium would not normally do: Patty appears differently from panel to panel. Natalie refuses to abide by the “stuttering” rule of comics. With her shrunken countenance and removed eyes from one panel to the next, Patty is no longer a character with a full, simple face into which people can project, a kind of visage that the comic theorist Scott McCloud argues is key to identifying with comic book characters. By utilizing the visual and playing with a specifically-comic form, I argued, Natalie enables a reader to better empathize with those suffering from lupus.

Or does she?

After my talk, I received an email from Natalie. She contends that language does a fine enough job expressing what experiencing illness is like and emphasizes that comics do not uniquely solve the “problem” that Woolf proposes. Rather, many people have unchangeably limited empathy for the ill, and neither words nor pictures can change that fact. Now a practicing nurse who has left the artistic field, Natalie criticizes my optimistic view of her comic and comics in general.

Here, I reprint a modified version of my critique of Natalie’s comic and Natalie’s criticism of my analysis, with her permission, to stage a conversation between critic and artist.

I. The Analysis

In the early nineties, Andrea Natalie was becoming an eminent artist in the LGBTQ+ comic scene. During that time, Natalie published a series of one-panel, Far-Side-esque cartoons called Stonewall Riots in gay newspapers and comic anthologies throughout the United States (“Dyke’s Delight #2”; Mangels 1). In 1991 and 1993, collections of Stonewall Riots received nominations for best humor book at the Lambda literary awards (“3rd Annual Lambda Literary Awards”; “5th Annual Lambda Literary Awards”). In a review of Stonewall, Betsy Salkind, a comedian, said that Natalie’s cartoons were better than Alison Bechdel’s concurrently published Dykes to Watch Out For (40). And the famed Bechdel herself praised Natalie’s work. Bechdel writes, “[Natalie’s comics have] such a nice feeling to [them]…[Stonewall Riots includes] a weird, sweet, cynical sensibility.” In a universe close to ours, Natalie is another Alison Bechdel.

But material reality impinges on the best of us. Natalie’s cartooning earned her little money, so, according to a 1993 interview with Josy Catoggio, Natalie entered nursing. Natalie has seemingly made no comics since that time.

“Caretaker Blues” was published in the all-women’s comic anthology Wimmen’s Comix (“Wimmen’s Comix”). In that Josy-Catoggio-led interview, Natalie praises artists like Alison Bechdel for making multi-panel strips because “it takes [Natalie] a long time just to do one panel. Drawing the same person over and over, panel after panel [is] hard, and it is a lot of work” (2:40-2:52). In “Caretaker Blues” rather than doing the humorous one-panel, Far–Side-esque gags for which she is known, Natalie challenges herself to take on a serious, long-form narrative.

Her experiment pays off.

In her interview, Natalie says that she herself is “not an artist” in comparison to other cartoonists because she cannot redraw characters competently from panel to panel (2:38-2:39). Though she does not state it using this term, Natalie indicates that she is not good at something fundamental to comics: the “stutter,” or the repetition of figures or images from one panel to the next. Chase Gregory defines the stutter as “the movement panel-to-panel [that] is rendered intelligible…by a repetition…the first frame is duplicated with a slight difference in the second” (84). In “Caretaker Blues,” Natalie’s difficulty duplicating characters from one panel to the next paradoxically works in the artist’s favor; in not making “intelligible” the movement, Natalie better draws what the unintelligible experience of lupus is like.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or simply “lupus,” is an autoimmune disease. The body’s white blood cells produce antibodies that, rather than attack foreign invaders, combat the organs, tissues, and cells of those suffering from the disorder (“Lupus [Systemic Lupus Erythematosus]”). These organs, tissues, or cells can be the joints, the kidneys, the skin, the heart, the blood, and, at the disease’s worst, the brain. The worst cases of lupus involve the extreme alienation of the body from itself; normally helpful cells begin to view one’s own organs as enemies. In “Caretaker Blues,” Natalie points out the flaws in words that are intended to convey the disorder and, instead, shows the illness’s break from the norm and the disease’s characteristic self-alienation by subverting the comic stutter.

The text of “Caretaker Blues” replicates the same flaws with words that Virginia Woolf identifies as language’s limits for describing illness. After Patty goes from “180 lbs. to 70 lbs.” and must stay at a hospital, the text above her notes that she has “inflamed skin,” “swollen joints,” “hair loss,” “anemia,” “low [blood] pressure,” and “diarrhea” (Natalie, “Caretaker Blues” 632) (see fig. 1). These words are thrown into a mass and a swirl around Patty, have no font shifts from ailment to ailment that would add specificity to their effects, and are so small and thin that they are nearly impossible to read. Implicitly with this bland, grocery-shopping-like list of agonies, Natalie criticizes the mere verbal identification of the symptoms of lupus as lacking or even obscuring what we see Patty go through.

However, there is one particular visual transition on this page that portrays the “shock” of experiencing some of the worst symptoms of lupus. During the movement from the third to the fourth panel on the page detailing Patty’s hospital stay, Natalie removes Patty’s eyes, one of the face’s most important parts for reader empathy (see fig. 2). Just before, Natalie had taken away Patty’s round visage but kept the eyes. Staring directly at you with a saddened expression, Patty’s repeated eyes not only help to make you feel one with Patty but also remind you that this increasingly emaciated figure remains her. Through most of the comic, Patty’s eyes are consistently big, focal items of her face that, even when “averting” the sight of the audience, often look as if they have pupils that are gazing askance at the reader (see fig. 3 [the pictures in this figure do not successively follow one another in the comic]). Empty, round faces with simple eyes—like what Patty has before the transition—help readers to identify with cartoon characters according to McCloud (36). Over the course of the hospital stay, we lose this visual shorthand for relatability, and a different means of identification takes its place.

In the fourth panel, Patty’s eyes are gone, replaced with dark shadow and a fully aside stare (see fig. 2). In “On Being Ill,” Woolf contends that sickness is so painful and isolating that people with illness reach a melancholic awareness unavailable to the healthy. Woolf writes, “It is only the recumbent who know[s] what, after all, nature is at no pains to conceal—that she in the end will conquer” (16). Being sick, especially with lupus wherein the body attacks itself, is so distant from humdrum existence that “only the recumbent…knows,” or only the sufferer comprehends, that conveying its effects with traditional words is difficult if not impossible. However, Natalie makes lupus’s self-alienating condition known by alienating Patty from the viewer. Natalie refuses to give readers what they want: a repeated Patty. Instead, we must see Patty as an almost inhuman object, a mass of scribbles with shadowed, empty eye sockets, to conceptualize how different it is from regular existence to have “seizures,” “hair loss,” “migraines,” “vomiting,” “diarrhea,” “swollen joints,” “anemia,” and “painful glands” almost all at once (632).

Alienating the reader from Patty throughout much of the hospital-stay page paradoxically makes Patty closer to the viewer because it forces a reader to work to understand Patty’s plight. Natalie does not draw Patty as a Mickey-Mouse-esque cartoon character who people can easily identify with, feel for, and perhaps condescend to. Rather, Natalie compels the reader to understand that this slight mass of scribbles with eyes in shadow is not only human and, thus, worthy of empathy but also that this being is suffering in ways almost totally foreign to most of us. Natalie’s not practicing the stutter in this passage both abides by and violates McCloud’s theory that the simpler the figure, the more readers can empathize with the character. Giving Patty her full-round face into which we can see ourselves and then ripping it away allows Natalie to show the complications in McCloud’s theory; sometimes, readers can have more empathy for inhuman, non-simplified characters in the right context.

II. Natalie’s Email

I usually drew a single-panel cartoon instead of a comic strip not because I have any objection to what you refer to as the “stutter,” but because I’m a crappy artist, and drawing multiple panels is tedious and boring. I never had the skill or patience to make characters and settings look the same from panel to panel, though I certainly admire artists like Alison Bechdel who can do that. “Caretaker Blues” is the only multi-panel I’ve ever done, and the reason Patty’s appearance changed from panel to panel is that she really did go through profound physical changes as a result of lupus. I was just trying to illustrate reality. She went from an obese woman to someone who weighed less than eighty pounds. Lupus caused systemic inflammation and nerve damage, and she went through a period of excruciating skin sensitivity and couldn’t even have sheets touch her body, and she lost the ability to stand, which is why she’s shown going from walking around in clothes to lying naked in a bed. I appreciate your wanting to explain the drawings in academic terms, but the truth is that I was just trying to draw what really happened.

I was surprised to learn Virginia Woolf felt English was inadequate to describe illness because she made such excellent use of it to convey her own experience. What I’ve seen, both before and after becoming a nurse, is that sick people are more than capable of describing their experiences with vividness, grace, and humor. The problem is in the listeners. Patty was severely ill and died at age fifty. She required assistance to stand and walk, had very reduced lung capacity, chronic diarrhea, and vomiting, was often in pain, suffered from profound fatigue, and her bones were so fragile she had over a dozen spontaneous fractures. Most of our friends readily grasped all this and were very sensitive to her condition and went to great lengths to accommodate her limitations. Other people, including her family members, treated her with disbelief, anger, roughness, ridicule, and refused to push her wheelchair or even to extinguish their cigarettes in her presence. This had everything to do with their lack of empathy and imagination and nothing to do with Patty’s ability to convey her experience. The problem lies not with the teller but with the receiver, and frankly even drawing people like that a picture makes no difference.

III. Reflection

Andrea Natalie herself stresses that no comic can motivate a reader who disbelieves in the plight of individuals affected by lupus to think and act more compassionately for those with the disease. Languages, even visual ones, have limits. Natalie emphatically writes, “[F]rankly even drawing people like that a picture makes no difference.”

Our dialogue is part of a long-standing question: can the visual express painful experiences in a way that words cannot? Elaine Scarry, despite her skepticism of pain’s communicability, derives a similar answer to mine: yes, visual art can create more empathy for those in agony.[i] Take one of Scarry’s examples—Sergei Eisenstein’s silent films often have individuals screaming in pain, but, of course, lack a yell’s associated noise. Scarry contends that these unvoiced shrieks “coincide…with the way in which pain engulfs the one in pain but remains unsensed by anyone else” (52). Eisenstein’s silent yells paradoxically allow an audience to be more compassionate toward his screamers than if these screechers howled their laments. Natalie’s tampering with the stutter—unintuitively not repeating an identifiable face—has a similar effect.

Surprisingly, Natalie, as a visual artist, does not rank images above language as an effective creator of compassion for suffering, noting that, no matter how a sick person “conveys [his or] her experience,” many people are incapable of comprehending the pain that those who are ill feel. Therefore, Natalie’s perspective not only casts a shadow of doubt on the ideals of those working with graphic medicine but also on the medical humanities overall. Natalie indicates that many people have such a “lack of empathy” and “imagination” that no kind of experience with art about illness will convince these unimaginative people to enact care, e.g., “push[ing] a wheelchair” or “extinguish[ing] a cigarette.”

I do not want to create a strict dichotomy between my position and Natalie’s. After all, Natalie indicates that only some people have the limited empathy that she derides. But perhaps, as I have tried to argue in this conclusion and Natalie implies, there is room for those working with graphic medicine to expand their imagination and listen to the hesitancy of our artists.

[i] Scarry also observes that images that can create empathy for the suffering, like ones that portray weapons, can also be used to display power bluntly (17-18).

Works Cited

“3rd Annual Lambda Literary Awards.” Lambda Literary, 13 July 1991, https://lambdaliterary.org/1991/07/lambda-literary-awards-1990/.

“5th Annual Lambda Literary Awards.” Lambda Literary, 13 July 1993, https://lambdaliterary.org/1993/07/lambda-literary-awards-1992/.

Charon, Rita. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. Oxford University Press, 2006.

Czerwiec, MK, et al.. Introduction. Graphic Medicine Manifesto, edited by Susan Merrill Squier and Ian Williams, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015, pp. 1–20.

“Dyke’s Delight #2.” Comics.org, Grand Comics Database, https://www.comics.org/issue/263324/. Accessed 3 Aug. 2022.

Gregory, Chase. “Thwarting Repair: Gutter, Stutter, Are You My Mother?” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, Sept. 2019, pp. 72–92. EBSCOhost, doi-org.libproxy.boisestate.edu/10.1215/10407391-7736049.

Green, Michael J, and Kimberly R Myers. “Graphic Medicine: Use of Comics in Medical Education and Patient Care.” The BMJ, vol. 340, 3 Mar. 2010, pp. 574–577. The BMJ, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c863.

“Lupus (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus).” Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, 19 Apr. 2021, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4875-lupus.

Mangels, Andy. “Contents Page.” Gay Comics, no. 15, Bob Ross, 1992.

Marchetto, Marisa Acocella. Cancer Vixen. Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. HarperPerennial, 1993.

Natalie, Andrea. “Caretaker Blues.” The Complete Wimmen’s Comix, edited by Gary Groth, vol. 2, Fantagraphics Books, Inc., Seattle, WA, 2016, pp. 630–633.

Natalie, Andrea. “Cartoonist Andrea Natalie Interviewed by Josy Catoggio.” 21 December 1993. Interview by Josy Catoggio. The Internet Archive, 3 May 2012, https://archive.org/details/pra-KZ4052.

Natalie, Andrea. E-mail interview with the author, 13 Jun. 2022.

Natalie, Andrea. Rubyfruit Mountain: A Stonewall Riots Collection. Cleis Press, Inc. 1993.

Salkind, Betsy. “Books.” Sojourner, vol. 16, no. 10, May 1991, p. 40. Archives of Sexuality and Gender, link.gale.com/apps/doc/BRYWOI704056440/AHSI?u=upitt_main&sid=bookmark-AHSI&xid=3f2f7072. Accessed 21 May 2022.

Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford University Press, 1985.

Woolf, Virginia, “On Being Ill.” On Being Ill. Paris Press, 2002. pp. 3-29.

“Wimmen’s Comix.” Women In Comics Wiki, FANDOM Comics Community, womenincomics.fandom.com/wiki/Wimmen%27s_Comix

Cover Image Source: “‘Caretaker Blues’ by Andrea Natalie, 1992. The main character of the comic, Patty, looks after her partner and her partner’s child.”