Written in collaboration with Dr. Megan Hunt, an anesthesiology resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The Anesthetic Soundscape

Prelude

The anesthesiologist approaches the patient’s bedside, introduces herself, and asks, “Have you had surgery before?” She listens to the lively rhythms of the heart and lungs, seeking out quiet clues of any conditions which may interfere with the day’s procedure. Finding none, she outlines the lengthy movements of the symphony to follow: the delicate intravenous hunt, the winding journey through the hospital halls, the agile transfer to the operating table, and the preparatory whoosh of supplemental oxygen.

“We will give you relaxing medication, we will place a breathing tube, we will monitor you throughout surgery, we will wake you up, and we will assist in your recovery,” she directs. She answers questions as the patient signs consent forms. “Keep your arms and legs inside the stretcher for the ride. Ready to rock and roll?” The overture is underway.

In the 2019 Routledge Handbook of the Medical Humanities, Claire Hooker and James Dalton argue for a critical merging of performance studies with medicine. In their rhetorical analysis, healing practices constitute staged rituals such that the performative quality of doctoring is made “inseparable from the process of healing” (Hooker and Dalton 206). They argue for a provocative reassessment of the traditional figure of the modern doctor as a kind of theatrical role, one which seeks to (re)present trustworthy authority over and over again to patient spectators.[1] The presentation of helpful overviews, the careful intake, and the calming quips attest to the value of this methodical, sometimes playful production. But does this model of performer (doctor) and audience (patient) hold when shifted to the operating room wherein a patient is rendered immobile and unconscious? Paying particular attention to the sonic dimension of surgical environments, a more collaborative possibility of understanding medicine as performance emerges in the figure of the anesthesiologist and in her invaluable, interpretive acts.

Interlude

Secured on the table, the patient is hooked up to several monitors. The familiar “beep, beep, beep” tones of the pulse oximeter start up, indicating the pace of the heart and the oxygen saturation in the blood. Against this baseline riff, the whir of the blood pressure machine kicks in, followed by an elongated chirping noise. Like a brief refrain, the patient repeats their name and intended procedure one final time before the anesthesiologist pushes medications inducing amnesia, analgesia, and akinesia. In soft submission, the patient falls asleep, their voice fading from the composition. After a beat, the room bursts into activity. Enter the routine rituals of intubation, positioning of the limbs to avoid pressure injuries, and administration of antibiotics and antinausea medication. Additionally, the floating, background warble of actual, recorded music commences. Many surgeons opt for soundtracks to accompany their craft, hauling speakers into the OR to both soothe nervous patients and to steady their own hands. The din of the space is neither pleasant nor discordant. Rather, it is like a coordinated musical movement—shifting, swelling, subsiding—as the surgical narrative progresses.

(Sounds recorded by Megan Hunt in operating room, February 28, 2023)

The anesthesiologist’s job is to ensure the number ends with her patient awakening unharmed, save the interventions of the day’s procedure. Shifts in the music of the operating room are her primary cues: alterations in sound or sudden, eerie silences require a flurry of rapid intervention.

A surgeon asks, “everything okay up there?” The anesthesiologist replies, “we had some hypotension but it’s under control now,” as she peers over the drapes to ensure the beeping sounds match their bodily referents. In the concert of the operating room, her roles are multitudinous. She listens with a keen ear as she supervises, becoming an instrument of pain mitigation and a mouthpiece for the patient who can no longer advocate for themselves.

“To be listening is always to be on the edge of meaning,” writes philosopher Jean Luc Nancy in his 2007 monograph, Listening (Nancy 22). According to his theory regarding sound and knowledge, in our hierarchy of human senses, “visual presence” has tended to be privileged as evidentiary over “acoustic penetration” (17). Certainly, perception and interpretation of visible information has always been the dominant mode of medical practice, as physicians are diligently trained in diagnostic observation. Alongside and alternative to this tradition, though, the anesthesiologist offers us a supplementary case study in sonic attentiveness and doctorly performance. She listens, straining toward and producing the medical meaning which hovers on the aural plane of the OR. She constructs a coherent narrative out of the scene’s many pings, chirps, timbres, and tones; she adjusts the instruments to produce a suitable melody for the success of the operation; and she verbalizes the needs of the silent patient on the table. In short, she acts at once as conductor, interpreter, vocalist, and, importantly, generous audience to the living music of the unconscious body’s still performing organs.

This kind of performance is different from the theatrical presentation of the pre/post-operative encounters discussed by Hooker and Dalton. Instead, in the operating space, we slide into a more ensemble-like, improvisational performance. Indeed, in an aside, Jean Luc Nancy actually likens auscultation to a form of music appreciation, drawing upon sounds themselves to produce material meaning (21). In this resonant mixture composed of the patient’s bodily signs, the technological hum of the equipment, and the well-calibrated ear of the anesthesiologist, a new kind of dynamic, collaborative, hermeneutic tune emerges. The anesthesiologist’s radical receptivity to and participation in the soundscape[2] of the operating room shifts our understanding of the stratified relationship between performer and audience, or doctor and patient, to one of group performance. All parties in this space have specialized parts to play, and the music of surgery is made possible and meaningful only by their shared involvement, their shared facilitation of sound, and the anesthesiologist’s holistic orchestration of the production as a whole.

Postlude

Following a procedure entailing general anesthesia, sound is actually the first sense reanimated for a patient. The gaseous anesthetics are slowly breathed out of the patient’s body, and the anesthesiologist watches the monitors for indication that the individual is beginning to notice sensations again. The patient hears fuzzy, disorienting noises and voices, though they cannot yet respond with words or movement. “Open your eyes and we can take out this breathing tube,” the anesthesiologist commands gently. Like magic, the remark sharply awakens the patient sharply to the acute discomfort of the tube. Though still dazed, they are ready to breathe on their own again; the device is removed.

Like a performance winding down to a close, the monitors are disconnected once the patient’s breathing stabilizes. They are taken to the post-operative wing. “I hope you have a speedy recovery. The surgery is all over,” the anesthesiologist says as the beeping and whirring of the machines die out, the final beats of the music ushering the patient into a state of recovery.

Performance, music, and sound have always held relevance in the medical profession, as “sound has reverberated throughout the history of technological and scientific advances” (Armitage). These qualities, however, are primarily envisioned as a supplemental area of humanities and arts expertise, harnessed most often for music’s therapeutic value in clinical spaces. There is undoubtedly strong evidence that the incorporation of music or expressive arts in healing procedures is widely beneficial to patient outcomes.

But what happens when we turn to the less obvious sites of medical sound production and examine them through humanistic frameworks? How might performance studies enable us to better understand the interplay of language, technology, bodily rhythms, and techniques of listening in medicine? To imagine doctors, patients, and inanimate tools as mutual participants in a sonic performance is to shepherd into existence an idea that medical encounters mark shared efforts in keeping time, expressing emotion, and producing harmonious outcomes. Through the figure of the attentive anesthesiologist, concentrated as she is on the many significant notes and riffs flooding the operating room, we can better recognize medicine itself as an intentional arrangement and analysis of meaningful noise.

Works Cited

Armitage, Hanae. “Sound Research: Scientific Innovations Harness Noise and Acoustics for Healing.” Stanford Medicine Magazine, Spring 2018.

Hooker, Claire, and James Dalton. “Chapter 19: The Performing Arts in Medicine and Medical Education.” Routledge Handbook of the Medical Humanities, Routledge, 2022, pp. 205–220.

Nancy, Jean Luc. Listening. Fordham University Press, 2007.

Footnotes

[1] See Erving Goffman’s scholarship on “dramaturgical analysis” for a longer discussion of how the artifice of performance is produced in medical spaces and other sites of social interaction.

[2] For a discussion of soundscapes and their exposure of the social characteristics which come together to create a sonic environment, see R. Murray Schafer’s foundational work, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (1994).

Image Credit

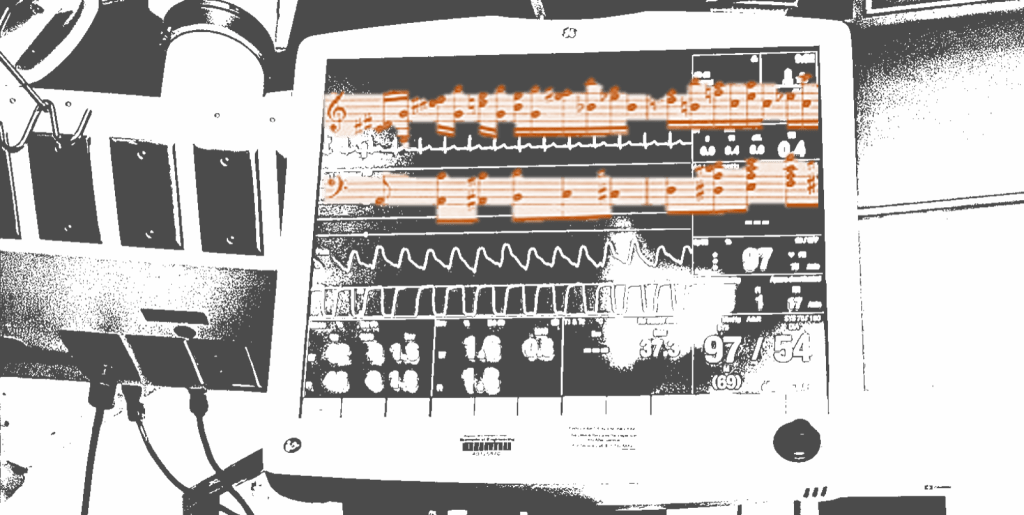

Black and white photograph of operating room monitor, Boston, MA, February 2023. Image taken by Megan Hunt.

(Overlaid music notes)–

“File: The University course of music study, piano series… (14577473997).jpg.” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. 31 Oct 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:The_University_course_of_music_study,_piano_series;_a_standardized_text-work_on_music_for_conservatories,_colleges,_private_teachers_and_schools;_a_scientific_basis_for_the_granting_of_school_credit_(14577473997).jpg&oldid=701099763>.