“Too much water hast thou, poor Ophelia,” remarks Laertes in the scene from Shakespeare’s Hamlet in which the Queen announces his sister’s death (4.7.211). More than a commentary on the way she died—drowned, surrounded by flowers, in a stream under a weeping willow—Laertes diagnoses Ophelia with watery excess. This infirmity was the essence of her languishing nature and physiology. Two centuries later, the drowning of wayward beauties became a preoccupation of Romantic poets and pre-Raphaelite painters. John William Waterhouse (1849-1917) produced three paintings of Ophelia and three more of her contemporary counterpart: the ephemeral character after which Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) entitled his 1832 ballad, The Lady of Shalott [Figure 1]. Many unhappy successors—both fictive and real—followed Ophelia and the Lady of Shalotts by going to the water, apparently to end their lives. Within the tragic-romance genre, the water itself emerges as an integral element of these women’s death scenes. Yet, as the trope of watery women reached into the twentieth century, the utter femininity of these women’s drownings was attributed to their beauty and the lovesick delusions that led them to their demise, rather than to Laertes’ diagnosis: that women were inherently made of “too much water.” In the early modern period, the gendered connotations of water in contemporary medical thought were what naturalized drowning as an inherently feminine form of death, giving rise to a persistent narrative that then continued for centuries after the medical theory that produced it had faded into obscurity. Reintroducing excess water as a condition from which the women of the drowned beauty trope suffered provides insight into the original significance of the apathetic dispositions which led to their deaths. It also revives an enduring question: did these women really drown themselves? Or rather, were they drowned from within?

The joint literary analysis of Ophelia and Shalott is hardly novel. Characteristic details of these stories bind them together and expose them for what they are: male fantasies of a quintessentially feminine death; a doomed trajectory that starts in lovesickness, is followed by hysteria and utter desperation, and finally ends in a watery scene of lifeless tranquility. The apparent suicides of both Ophelia and the Lady of Shalotts reveal a myriad of contradictions which, when taken together, encapsulate the antithetical essence of male poets’ sexual desire for the women only when they reached the most pitiful of states: self-destruction instigated by romantic rejection. The watery environment allowed pre-Raphaelite painters to depict the dead women as serene and beautiful; corporally insensitive, yet sensual to behold [Figure 2]. In their passivity, the women are aloof, verging on arrogant—comparable to the high-born ladies in chivalric tales—a conviction that can be derived only from the assumption that they are still, somehow, perceptive of the viewer’s gaze upon their bodies. Ophelia’s suspension in the water—hair swaying in the ripples, robes billowing—and the current’s placid guiding of the Lady of Shalott into Camelot, provide evidence against the irrefutable petrification of death. But then again, Ophelia and Shalott are marionettes, subject to the whims of the water. In these scenes, the water facilitates a disturbing ideal of femininity, one that romanticizes passivity to the point of death and preserves corporeal beauty in oblivion.

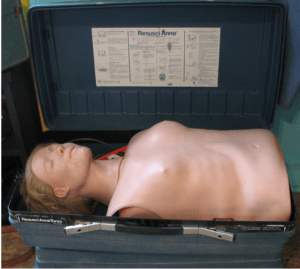

The idea that drowned women possessed a certain pathetic beauty was not confined to the imaginations of Elizabethans, or nineteenth-century poets and painters. Rather, the notion permeated the cultural consciousness, resurfacing even in the most utilitarian of twentieth-century tools for the emergency treatment of drowning: CPR mannequins. In the 1960s a first-aid training tool, colloquially known in the United States as “CPR-Annie,” had a face based on the death mask of a smiling young woman [Figure 3]. The popularly-held origin story of the visage, called “L’inconnue de la Seine,” was that a woman had been pulled from the Seine River in Paris in the 1880s or 1890s and the coroner at the city morgue—who suggested suicide was the cause of her death—took the unusual step of making a death mask, compelled as he was by her beauty (Grange; Sciolino). Throughout the early twentieth century, the mask was often replicated, widely sold, and hung in living rooms across Europe—inevitably piquing viewers’ curiosity about the particulars of her tragedy, and, in lieu of satisfying answers, inviting their invention (Montier 47). L’inconnue had been an orphan teenager driven to fatal despair when she was abandoned by her lover, an Englishman of superior social station; or, some say, she had fallen in love with a man who loved another; or, according to others, her beau left her because she was pregnant (Grange; Sciolino; Phillips 322). The stories are updated versions of archetypical drowned beauties, merely replaying Hamlet’s rebuff of Ophelia [“Get thee to a nunnery!”(3.1.131)] or Lancelot’s careless dismissal of The Lady of Shalott [“He said, “She has a lovely face, God in his mercy lend her grace” (IV.52-53)]. Though she was a real body, L’inconnue was not a real woman. Rather, her life was overwritten by a familiar narrative precipitated by male romantic rejection, one revealing of the cultural preoccupation with lovesick, beautiful women, and one in which women’s watery death scenes became eulogies to a distinctly apathetic version of femininity.

By the time the face of L’inconnue had reached ubiquity in the mid-twentieth century, recognized by art collectors and teenage lifeguards alike, the significance of the role of water in the women’s stories had subsided. A return to Ophelia’s story, which initiated the drowned beauty trope, reveals that water was elemental in the gendered nature of the women’s deaths precisely because it was, of the four natural elements, the one most associated with women in the early modern period. Humoral theory, which dominated medical thought in early modern Europe, proposed that the body was composed of four humours, each of which was aligned with one of the four elements. A healthy body maintained a harmonious composition of the four humors, which were further distinguished by their quality as either hot/cold or wet/dry: blood was associated with air (hot & dry), yellow bile with fire (hot and wet), black bile with earth (cold & dry), and phlegm with water (cold & wet).

Humoral theory further stated that males were naturally hot, prone to valiant action or, at worst, ‘hot-blooded’ distemper. Women, on the opposite side of the humoral spectrum, tended towards cold humours, which predisposed them to melancholic and phlegmatic characters (Paster, 13). While the early modern ideal of masculinity promoted the virtues of moderation and reason—qualities that supposedly allowed men to control themselves, and their humors—women were typically faulted for their childish inability to control their emotions. Accordingly, women were seen as more prone to humoral upset and the negative emotional and physiological conditions that ensued—e.g., melancholia and lethargy—than men were to violent outbursts.

An individuals’ gender therefore influenced their humoral compositions and behavioural traits. The predominance of any one humor produced specific, albeit benign behaviours. A surfeit of any humour, however, could be dangerous (Steggle, 223; Ekström). While a predominance of blood caused extraversion, an excess could cause maniacal ferocity, and the valiance produced by yellow bile could topple over into arrogance and anger. Black bile could produce scholarly introspection, or melancholia (Paster, 83). In moderation, the cold and watery humor, phlegm, could produce calm. In excess, however, it induced the sort of dispassionate lethargy that could explain the lowered states of consciousness that led Ophelia and Shallot to their deaths. Thus, Laertes’s response upon hearing the news of his sister’s death, “Too much water hast thou, poor Ophelia,” refers to the watery surplus of phlegm in her body that corroded her disposition (4.7.211). Hamlet’s strange wish during his farewell to Ophelia, that she be “as chaste as ice,” also comes into focus (3.1.146). He desired for Ophelia to be so inundated by the coldest and wateriest female humors that she was frozen into abstinence. This language of women’s humoral imbalance is still present in Tennyson’s description of the Lady of Shalott, whose, “Blood was frozen slowly,” as her body floated into Camelot (1842 version, IV.30) [Figure 4].

Humoral theory’s proposition, that there was an inherent wateriness to women, raises the question of the true cause underlying the deaths of the drowned-beauty archetype, a question with which Shakespeare himself contended. In some parts of early modern Europe, gravediggers were classified under the same guild as doctors and apothecaries, to whom they often rendered their services (Park, 17). The close association between gravediggers and medical practitioners is borne out by the medical opinion Ophelia’s gravedigger provides on her death. Speaking to Hamlet, he says: “If the man go to this water and drown himself, it is (will he, nill he) he goes; mark you that. But if the water come to him and drown him, he drowns not himself” (5.1.15.). The women’s symptoms before their deaths—delusion, singing to themselves, and, as Tennyson put it, being in a “trance” state with “a glassy countenance”—suggests that the women of this tragic narrative arch were drowned by the rising phlegm in their own bodies long before they ever took to the water themselves (IV.20-22).

Images:

Crane, Walter. The Lady of Shalott, 1862, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund. https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:1285

Castañda, Adriàn. Resusci Anne, 2017. Wikipedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Resusci_Anne_-_CPR_dummy.jpg

Millais, John Everett. Ophelia, 1851-1852, oil on canvas, Tate Britian.1https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-ophelia-n01506

Waterhouse, John William. The Lady of Shalott, 1888, oil on canvas, Tate Britian. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/waterhouse-the-lady-of-shalott-n01543

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Lord Tennyson, Alfred. “The Lady of Shalott (1842),” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/ 45360/the-lady-of-shalott-1842

Lorn Tennyson, Alfred. “The Lady of Shalott (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45359/ the-lady-of-shalott-1832

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet from The Folger Shakespeare. Ed. Barbara Mowat, Paul Werstine, Michael Poston, and Rebecca Niles. Folger Shakespeare Library, [April 13, 2023]. https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/hamlet/read/

Secondary Sources:

Ekström, Nelly. “Shakespeare and the Four Humours,” The Wellcome Collection, https:// wellcomecollection.org/articles/W-MM-xUAAAinxgs3

Grange, Jeremy. “Resusci Anne and L’Inconnue: The Mona Lisa of the Seine,” October 16, 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24534069

Montier, Jean-Pierre. “Le Masque de l’Inconnue de La Seine: Promenade Entre Muse et Musée,” Word & Image (London. 1985) 30, no. 1 (2014): 46–56.

Park, Katherine. Doctors and Medicine in Early Renaissance Florence. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1985.

Paster, Gail Kern. Humoring the Body : Emotions and the Shakespearean Stage. Chicago ;: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Phillips, David. “In Search of an Unknown Woman: L’Inconnue de La Seine.” Neophilologus 66, no. 3 (1982): 321–327.

Sciolino, Elaine. “At a Family Workshop Near Paris, the ‘Drowned Mona Lisa’ Lives On,” Nyew York Times, July 20, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/20/world/europe/paris- mask-picasso-truffaut.html

Steggle, Matthew, ‘The Humours in Humour: Shakespeare and Early Modern Psychology’, in Heather Hirschfeld (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Shakespearean Comedy, Oxford Handbooks (2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 9 Oct. 2018),