Clothing in Postcards of Algerian and Moroccan Women

In many ways, garments were a marker of disparity between Vietnamese and North African colonial portraiture. In Algeria and Morocco, postcards were often organized around the veiled—or rather, unveiled—woman, a theme central to Orientalist art and photography. Colonialist photographers, such as Jean Geiser, Rudolf Lehnert and Ernst Landrock, typically presented bodies of unclothed women from the waist up, displaying a diaphanous veil as an accessory.

This practice became de rigueur in the late 19th and early 20th century: the bodies of North African women were repetitively objectified in postcards, with the female breast systematically showcased as objects of visual consumption. It was common for these photographs to feature pornographic images of pre-pubescent girls accompanied by titles such as “Jeune Maure” (Young Moor) or “Fillettes Arabes” (Little Arab girls) that functioned as a fetishistic device.

The Phantasm of the Veil

In the colonial context, the veil assumed multiple meanings for the French. On the one hand, the French exoticized the veil into a phantasm of the Oriental female. The photographers employed visual strategies to transform the veil from its original function of female concealment to a symbol of sexual attraction, thereby perpetuating the stereotype of (North) African women as lascivious.

This phenomenon is described by what Lisa Z. Sigel, a historian of pornography and eroticism, has termed “staged nakedness.” French photographers utilized techniques to remove the symbolic barrier of inaccessibility represented by the veil. These included a cropped visual field and close-up camera angles. The models’ gazes were also manipulated, with suggestive looks directed at the camera or downwards, inviting voyeuristic viewers to indulge their ‘Oriental’ fantasies.

The aim of inducing frisson is particularly noticeable in many postcards of fully-veiled women in public spaces. They either featured unequivocal captions that referenced the exotic theme of the harem or included titillating details, such as a glimpse of high heels, which played into the eroticization of the fully-veiled woman.

On the back of a 1905 postcard entitled Algeria Scènes et Types, Mauresque Voilée portraying a fully-veiled woman with only her heels visible, an unknown traveler to Alger wrote to his friend: “If you could see this procession of young girls, you would have a good time. Most wear baggy pants down to the ankle, strawberry pink or almond green blouses, and ponytails twisted in a sash that conceals everything and raises like a horn. Splendid eyes, innocent look… they will be veiled at puberty.”

The Martinique-born psychiatrist and anti-colonial political philosopher Frantz Fanon coined the term “cult of the veil” to refer to the French fixation with it. He noted that the European man associated the veiled Algerian woman with a sense of “romantic exoticism, heavily infused with sensuality.” According to Fanon, the veiled Algerian woman, who sees without being seen in the public sphere, frustrated the colonizer: “She does not yield herself, does not give herself (…) The European faced with an Algerian woman wants to see.” He described the political doctrine of the colonial administration in the following way:

If we want to destroy the structure of Algerian society, its capacity for resistance, we must first of all conquer the women; we must go and find them behind the veil where they hide themselves and in the houses where the men keep them out of sight.

The Politics of Unveiling Women

Alternatively, the veil was viewed as antithetical to French culture—that is, a symbol of the oppression of Muslim women, who were perceived to be subject to a misogynistic religion and archaic practices and beliefs. Thus, the photographic portrayal of “unveiled” Algerian and Moroccan women served as more than a means of catering to the Western viewer’s fascination with exoticism. Instead, it became a potent symbol of French colonial dominance over the ‘Orient,’ representing an act of imperial deliverance for indigenous women.

This was primarily fueled by the ideology of the French mission civilisatrice, which formed the core of French colonial policy. The underlying principle of the civilizing mission was conviction in the superiority of French culture and civilization, hence the mission to “civilize” colonial subjects. In 1931, the geographer Émile-Félix Gautier noted: “We are full of pity for cloistered and tyrannized Muslim women; their emancipation appears to us as a duty of humanity and a law of progress.”

The preoccupation with “saving” Muslim women is also apparent in the writings of 19th-century French feminists. The historian Carolyn Eichner observes that even those who were explicitly anti-imperialist often linked gender liberation to various forms of imperialism. For instance, Hubertine Auclert, a prominent suffragette, and famous Communard woman Paule Minke both maintained that the spread of French culture in Algeria would lead to the emancipation of women from “Islamic oppression.” Rather than question the role colonization might have played in women’s subjugation, they espoused the civilizing mission’s principles. They believed in its ‘usefulness’ in elevating the colonies and indigenous women’s status.

Fanon’s analysis of the French desire to unveil women is especially relevant in understanding the political significance of the veil during the Algerian War of Independence (1958-62). During the war, Muslim Algerian women emerged as active participants. Many unveiled Algerian Muslim women joined the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), the anticolonial revolutionary movement that waged war against France. At the same time, the FLN instrumentalized the veil, wherein women hid bombs and smuggled weapons beneath their haik, the traditional white Algerian veil. The veil’s political symbolism underwent a transformation, shifting from the expression of religious modesty to an instrument of resistance and nationalist struggle.

As Algerian women joined the struggle, French propaganda intensified its campaign to unveil them as a means of demonstrating Muslim women’s endorsement of European values, thereby highlighting the supposed success of assimilation in French Algeria.

To serve this purpose, the French army orchestrated the public unveiling of Algerian Muslim women in May 1958, with the help of the wives of prominent French generals such as General Salan and Colonel Massu. During these mass-staged spectacles, Algerian women were persuaded, paid, or forced to remove their haik before a crowd and adopt the slogan “kif kif la francaise” (roughly: let’s be like the French woman).

Despite never wearing a veil before, Monique Améziane was one of the women coerced into participating in a public unveiling ceremony to save her stepbrother’s life, who had been detained and tortured by the French army.

Fanon criticized the colonial and symbolic implications of the demonstrations, arguing that “every veil that fell, every body that became liberated from the traditional embrace of the haïk (…) was the negative expression of the fact that Algeria was beginning to deny itself and was accepting the rape of the colonizer.”

Clothing in Postcards of Vietnamese Women

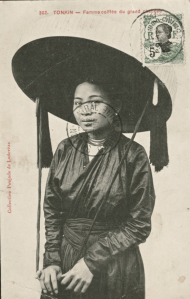

While the strategic use of clothing, or its lack thereof, conveyed North African women as oppressed or alluring, Vietnamese portraiture, conversely, leveraged clothing to reinforce stereotypes of Asian feminine submissiveness. Photographers often enveloped Vietnamese women in modest and shrouded clothing to conform to the image of sobriety and decorum that French colonial society expected from Asian women. Others drew from chinoiserie and contemporary European photographic portraiture to convey codes of social respectability. Both perpetuated the Orientalist discourse of Indochinese women as discreet, civilized, and modest.

According to Jennifer Yee, Vietnamese women were seldom presented in terms of sexual availability in colonial imagery; French historian of colonial Vietnam Isabelle Tracol-Huynh concurred that Asian women were presented as less sensual than North African women, with “no sensuality and no nudity.” Although less prevalent, sexualized representations of Indochinese women in postcards (specifically Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos) also existed. These hypersexualized portrayals also featured young women in voyeuristic, staged scenes. They were frequently captioned with phrases such as Jeune Fille à la Toilette (Young Girl Bathing Herself), mass-produced during the late 19th and early 20th century.

This iconography was mainly rooted in racial myths and prejudices that promoted the idea of Vietnamese women as sexually alluring. French colonizers commonly used the term congaï, ‘little girl,’ to refer to Vietnamese women as concubines and paramours. This trope was popularized in novels such as La Jaune et le Blanc (1927) and in prevailing songs such as La Petite Tonkinoise (1906), famously sung by Josephine Baker in 1953.

Colonial newspapers, too, became an essential vehicle for disseminating discourses on the unbridled sexuality of Vietnamese women. The popular La Revue Indochinoise cautioned French men against taking Vietnamese women as wives due to their “completely degrading morals.” According to the journal, the Vietnamese wife was a “monster of perversity” who was “incapable of fidelity.” The value of virginity, writes the journal, was deemed much lower for “the Annamite women and indigenous societies in general than for [European societies].” In another issue, the journal reiterated that Vietnamese women were drawn to prostitution from a young age. Her predispositions towards immoral behavior and perfidiousness meant that the European man would inevitably be cuckolded by his indigenous partner.

One example of the prevalence of the colonial narrative of the ‘easily bedded’ Vietnamese woman is evident in a scribbled message written by a Frenchman settled in Vietnam on the back of a postcard entitled Jeunes Congaïs: “My dear Charles, which one do you prefer? Me, I take this one….”

Although noticeably outnumbered by their North African counterparts, the commercialization of these postcards and dissemination of such oriental discourses in diverse media outlets reveal a diversity in Western representation of Indochinese women, oscillating between depicting them as coy and modest on the one hand and salacious on the other. Most significantly, it indicates the circulation and permeability of French colonial and racial discourses surrounding indigenous women within the imperial space.

The last and final part of the article will consider how colonial postcards cannot be dissociated from their colonial contexts.

Works Cited

Primary sources:

Gautier, Emile-Felix. Moeurs et Coutumes des Musulmans. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. Geertz, Clifford, 1931.

La Revue Indochinoise. BNF RétroNews. March 1, 1914.

Lévy Fils et Cie, Algeria Scènes et Types, Mauresque Voilée, 1905. African Postcard collection, EEPA 1985-014, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Secondary sources:

Eichner, Carolyn J. Feminism’s Empire. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022.

Fanon, Frantz. “Algeria Unveiled.” In A Dying Colonialism, trans. Haakon Chevalier. New York: Grove Press, 1965.

Sigel, Lisa Z. “Filth in the Wrong People’s Hands: Postcards and the Expansion of Pornography in Britain and the Atlantic World, 1880-1914:” Journal of Social History 33, no. 4 (2000): 859-885.

Tracol-Huynh, Isabelle. “Between Stigmatisation and Regulation: Prostitution in Colonial Northern Vietnam.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 12 (2010): S73-S87.

Tracol-Huynh, Isabelle. “La prostitution au Tonkin colonial, entre races et genres.” Genre, Sexualité & Société 2 (2009).

Yee, Jennifer. “Recycling the ‘Colonial Harem’? Women in Postcards from French Indochina,” French Cultural Studies 15, no. 1 (2004): 5-19.

Cover image: Jean Geiser, Jeune Mauresque, postcard, 1910s (Studio Delcampe: Algers, Algeria).