In the spring of 1795, Japanese physician Ōtsuki Gentaku (大槻玄沢,1757–1827) recalled the time he spent in his youth with Tatebe Seian (建部清庵,1712–1782), his mentor in medicine. Through his career as a specialist in external medicine (geka), Seian developed an enthusiasm for Western learning and Dutch studies (rangaku) (Takebe, Sugita, and Sugita 1795, preface). Taking off during the eighteenth century, rangaku introduced European scholarship on medicine to Japanese intellectuals through Dutch-language books and their translation. Deshima, a small artificial island off the shore of Nagasaki in southwestern Japan, served as a designated trading post between Dutch traders and their Japanese counterparts during this period (Clulow 2014). There, local interpreters facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas alike, whose mediating role in the transmission of knowledge seemed to have inspired both curiosity and suspicion from Seian, according to Gentaku’s recollection.

I was in the company of the revered old Tatebe Seian when I was young. The old mister often lamented: “From ancient times to present day, no one in Japan or China has attained the craft of surgery. And recently in our country, those who enjoyed fame through it mostly received their instruction from Nagasaki interpreters. They develop their theories by picking up Dutch people’s castoffs and supplementing those with the doctrines of physicians of Chinese medicine. What is there to talk about when it comes to this so-called ‘addition of a dog’s tail to the fur of a sable’? Without learning the Dutch speech and translating their books, how could one possibly obtain their truths?” (Takebe, Sugita, and Sugita 1795, preface)

Ōtsuki Gentaku relayed his teacher’s dissatisfaction while composing a preface to what came out in print during the autumn of 1795 under the title of Oranda iji mondō, or “Inquires and Responses on Matters of Dutch Medicine.” Spanning two volumes, the publication consists of four letters between Tatebe Seian and Sugita Genpaku (杉田玄白, 1733–1811) during their correspondence from 1770 to 1773. A physician by occupation, Sugita Genpaku earned a well-deserved reputation among his contemporaries for contributing to the Japanese translation of Dutch-language medical texts, so much so that Seian, having learned of Genpaku’s endeavor, sent both Gentaku and one of his sons away to study under the latter’s guidance (Takebe, Sugita, and Sugita 1795, preface). Emerging from professional exchanges and personal relationships as such was a social network of physicians, which became an important force behind the transmission of European medical thoughts in Tokugawa Japan (1603–1868) (Nakamura 2005; Jackson 2016).

Unfolding on the pages of Oranda iji mondō is a dialogue that exceeds the boundaries of a merely technical Q&A about the body of knowledge known in Tokugawa Japan as “Dutch medicine” in any absolute, isolated form. Propelling Seian to seek Genpaku’s insight was as much what Dutch medicine might look like in Holland as what it never seemed to be in Japan. As Seian speculated in his first inquiry, “although Dutch people come to Japan every year, and their external medicine is in sight, we do not see their internal medicine. Are there no internal medicine physicians in Holland?” (Takebe, Sugita, and Sugita 1795, 1).

At that time, all Seian had observed was the rough equivalence between “Dutch medicine” and a therapeutic approach that relied on the external application of medicinal creams and oils in lieu of the administration of oral pharmaceuticals. Regarding the authenticity of books labeled as instructions of Dutch-style external medicine and circulating in Japan, Seian further argued that “[those] were not works written by Dutch physicians. Rather, they appear to be the result of asking interpreters questions and writing down what one has heard” (ibid., 2). To complete the allegedly “Dutch” medical book, compilers would “select and gather excerpts from sections on external medicine from Chinese medical books and put together arguments about disease” (ibid., 2–3). In Seian’s conclusion, such publications in no way represented “genuine (shōshin)” Dutch-style medicine (ibid., 3). The direct textual translation of medical books written in Dutch, in turn, became an imperative for overcoming what was lost or distorted through verbal interpretation.

Yet what Seian meant by “translation (honyaku)” was not necessarily as straightforward as one might assume. Despite openly rejecting Chinese theories on external medicine, Seian embraced the Chinese script for its practical value without a second thought.

Even with the transmission of Dutch medical books, there will be no use of them when we do not know that country’s native script (kokuji) and language (gengo). Just like Kumārajīva‘s translation of Buddhist sutras in China, in Japan, too, if there is an erudite to translate Dutch medical books and render them into the Chinese script (kanji), the genuine Dutch-style will develop, and external medicine that borrows not from Chinese books will become established. On top of that, the subtle arts of [Dutch] gynecology and pediatrics, among others, will also develop. (ibid., 3–4)

In Seian’s vision, the authenticity of the Japanese translations of Dutch medical books meant both to purge their pages of any influence from Chinese medicine and to adopt the Chinese script as the tool of writing.

The “Chinese problem/solution” in the textual transmission of medical knowledge in East Asia was not lost on Seian’s correspondent Genpaku. While Seian was intrigued by Dutch medicine in juxtaposition with Chinese medicine, Genpaku was perceptive of the parallel between literary Sinitic (kanbun) and Latin. In one of his responding letters to Seian, Genpaku divided the world into four parts: Asia, Africa, Europe, and America.

Japan, China, Korea, and Ryukyu, among others, belong to Asia, and while their speech (kotoba) differs from one another, their scripts (bun) are the same script. These countries communicate with and understand each other if the writing is done in the literary Sinitic script (kanbun). Similarly, the speech by which Holland, France, and others in Europe communicate and understand each other is called Latin…. (ibid., 14–15)

Genpaku’s comparison of literary Sinitic and Latin is striking because it preceded Sheldon Pollock’s influential framework for understanding the historical interactions between a cosmopolitan literary language and its local, vernacular counterparts, whose case study focuses on Sanskrit (Pollock 2006). It also demonstrated the self-awareness that a group of Japanese physicians possessed and/or shared with one another as they navigated not only dissimilar languages, but also the distance and linkage between speech and script, along with the question of identity in pursuing or rejecting medical knowledges originating from different parts of the world. Even today the role that literary Sinitic played in the history of writing and the textual transmission of knowledge in East Asia remains relevant, over two centuries since Genpaku’s fleeting commentary on the nature of language and writing in transnational contexts. Earlier this year, a six-volume series themed “Language, Writing and Literary Culture in the Sinographic Cosmopolis” came into publication.

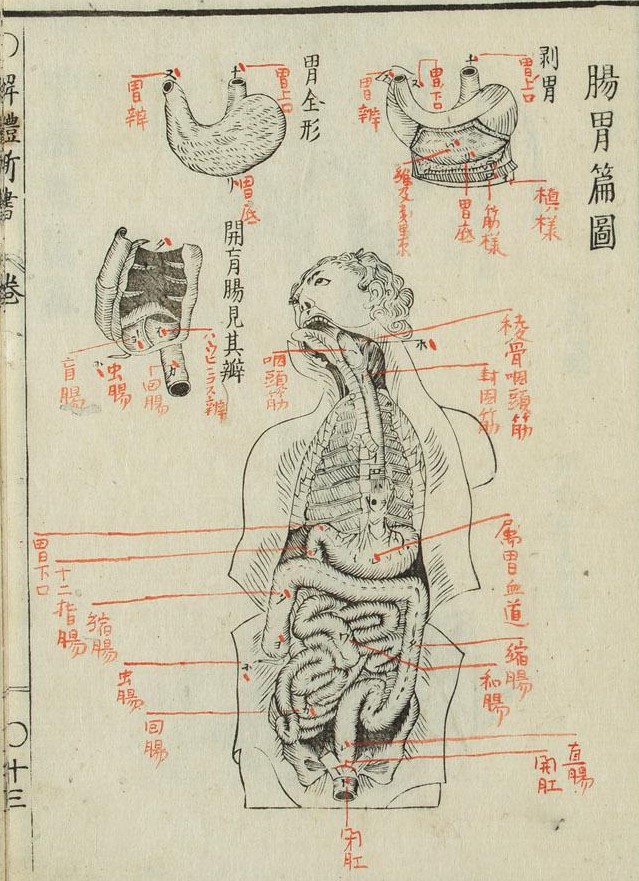

Following the three-year letter correspondence between Genpaku and Seian was the 1774 publication of Kaitai shinsho, or “New Text on Anatomy,” the Japanese translation of a Dutch translation of the work of German anatomist Johann Adam Kulmus (1689-1745). Genpaku poured his heart into the project—a Japanese translation of a European-language text achieved largely by utilizing the literary Sinitic script. This project, along with the overwhelming presence of medical books published in Tokugawa Japan in literary Sinitic, with authors of Japanese, Chinese, and/or Korean origins, begs the question of whether it is constructive to assign clear-cut language codes such as “Chinese” and “Japanese” when cataloging those books in an English-language context. Whose words are those? “Whose words are those,” indeed.

Note: Per convention, all the Japanese names are rendered family name first.

Featured Image

Sugita Genpaku. 1774. Kaitai shinsho. Tōbu [Tokyo]: Suharaya Ichibē. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chiikigakusaga_kaitaishinsho1-0026.jpg

Works Cited

Clulow, Adam. 2014. The Company and the Shogun: The Dutch Encounter with Tokugawa Japan. Columbia Studies in International and Global History. New York: Columbia University Press.

Jackson, Terrence. 2016. Network of Knowledge: Western Science and the Tokugawa Information Revolution. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Language, Writing and Literary Culture in the Sinographic Cosmopolis. 2019. 6 vols. Leiden: Brill. https://brill.com/display/serial/SINC.

Nakamura, Ellen Gardner. 2005. Practical Pursuits : Takano Chōei, Takahashi Keisaku, and Western Medicine in Nineteenth-Century Japan. Cambridge, Mass: Distributed by Harvard University Press.

Pollock, Sheldon I. 2006. The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Takebe, Seian, Genpaku Sugita, and Hakugen Sugita. 1795. Oranda iji mondō. Vol. 1. Edo: Shisekisai. https://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/ya09/ya09_00957/index.html.