- Foreword by author: this series of research centers around the mutual impact between medicine and diplomacy in the history of U.S.-Japan medical exchange and collaboration. It will explore how key agencies, in both the medical and diplomatic spheres, pursued U.S.-Japan medical exchange in the middle of ups and downs in a bilateral relationship.

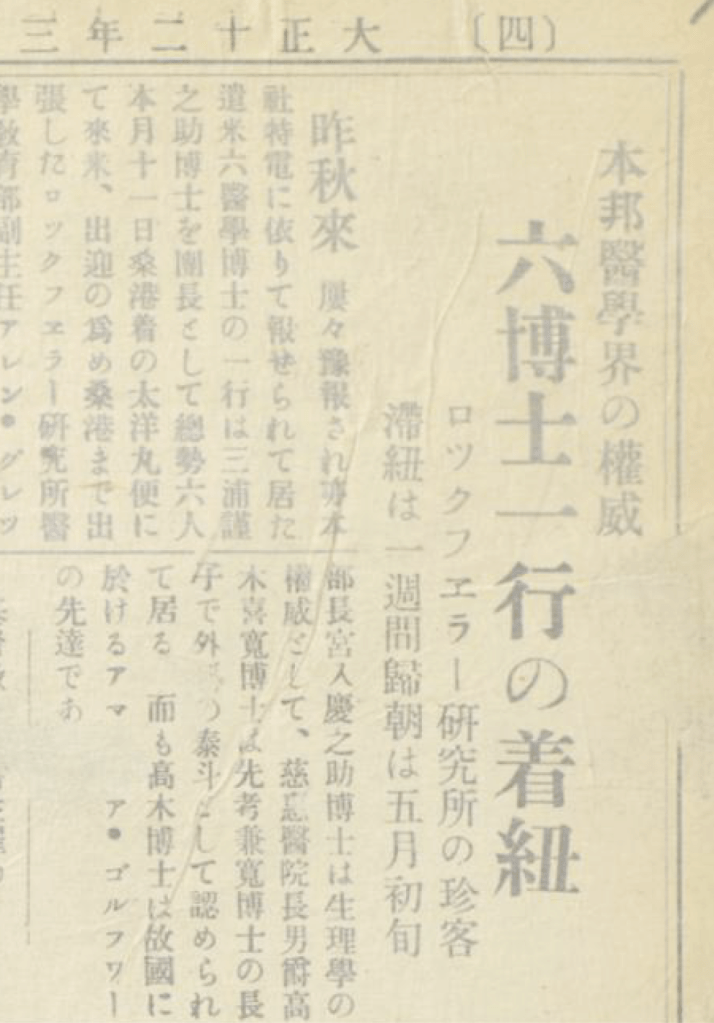

On March 21, 1923, San Francisco port had some special visitors from Yokohama across the Pacific. On board the transpacific ocean liner Taiyō Maru (大洋丸) were six prominent Japanese medical scientists (Nyūyōku shinpō).[1] Led by Tokyo Imperial University Professor and internist Miura Kinnosuke (三浦謹之助), these medical men formed Japan’s first official medical commission to the United States. The commission busily traveled to 22 cities. There, they met leading professionals in top-tier medical schools, hospitals, and research institutes. In May, they returned to Japan, with “a good many books, some instruments,” and extended knowledge of medical science in the United States (Gregg).[2]

The visit was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and endorsed by Japanese Ministries of Education and Foreign Affairs. Arriving around the same time with Japan’s new ambassador Hanihara Masanao (埴原正直) in the United States, it was hoped that this visit would help bring about smoother US-Japan scientific exchange and improved diplomatic relations. In the words of Rockefeller Foundation president George E. Vincent and Japanese Foreign Minister Uchida Kōsai (内田康哉), the commission was designed to not only “benefit medical studies and medical workers” in the United States and Japan; it would also help “enhance mutual understanding and friendship” between the two nations (Uchida, Vincent).[3]

Since the turn of the last century, mutual approach between American and Japanese medical communities has increased. This mirrored the expanded U.S.-Japan diplomatic contact, with both similarity and conflict of interest, in Asia-Pacific (Auslin, 2011).[4] It particularly accelerated after the outbreak of World War I. The war caused a pause to the exchange of personnel and knowledge between Japan and Germany. Roger S. Greene, a former diplomat and later a Rockefeller Foundation medical official in China, astutely discerned this golden opportunity to enhance American influence in the medical world in East Asia:

“The temporary break between Japan and Germany is already tending to make Japanese medical men look more to this country [the United States] than they have hitherto been disposed to do. If we can win over this influential class of Japanese, I think that we shall have no occasion to fear Japanese official jealousy, which may otherwise interfere seriously with the development of our plans [in China] …”[5]

In Japan, many seconded Greene’s view, particularly those associated with St. Luke’s Hospital—the only hospital under American influence in Tokyo. Dr. Rudolf B. Teusler, its founder and physician-in-chief, championed building the facility into a center for U.S.-Japan medical exchange. He believed in the necessity and importance of promoting American medicine in Japan, where hospital practice could be accordingly improved:

“Incidentally it [St. Luke’s Hospital] would serve to direct the thought of medical men in Japan towards American Medicine and surgery and assist in opening the way for sending their post-graduate men to American universities and hospitals. Until now German medicine has held almost undisputed sway in Japan and no more opportune time than the present could be found to rectify this very one sided development.” [6]

During World War I, Teusler became more of an insightful unofficial diplomat than a simple doctor. He worked closely with Japanese politicians and entrepreneurs like Ōkuma Shigenobu (大隈重信) and Shibusawa Eiichi (渋沢栄一) who emphasized U.S.-Japan amity. By 1917, he promptly acquired a new building and a new name for his hospital—St. Luke’s International Hospital (St. Luke’s International Hospital).[7] The Japan Advertiser, once “the Far East’s premier English language newspaper,” praised the new hospital as “a friction remover” (East View).[8] It not only opened the door for future Japanese medical students to study in the United States but also strengthened U.S.-Japan friendship (“The New St. Luke’s).[9]

The project to facilitate the training of Japanese medical professionals in the United States also came about while the new hospital was under construction. In late 1915, Teusler began to actively help Japanese medical students further their study and training across the Pacific. For this purpose, he reached out to prominent American and Japanese medical specialists, Japanese government officials, and the Rockefeller Foundation, for professional and financial support. Through Teusler’s endeavor, a committee on this matter began to take shape in the United States in December 1915. The news was welcomed by Japanese officials and medical men sharing Teusler’s enthusiasm. In December 1916, the Japanese committee of post-graduate study for Japanese students in the United States was established. In 1918, the American committee, chaired by Dr. Richard M. Pearce, was also established.[10]

Despite the repeated mention of “American medicine” in the correspondence between Teusler, Rockefeller Foundation, and American medical specialists, its meaning remained rather unclear. Dr. Richard M. Pearce dropped a hint about its definition in his report on Japanese medical education and practice. In June 1921, after visiting many medical schools and institutes in Japan proper and its colonies, Pearce spoke highly of the laboratory development and research activity” in Japan. However, he also pointed out Japanese medical students’ lack of clinical training. This, by contrast, was a pivotal part in American medical education system:

As to methods of clinical teaching, there is room for some criticism in connection with the individual work of the student. It should be remembered, however, in this connection, that Japan has followed the German and not the English system and has therefore made no attempt to develop the English clinical clerk system or the individual ward work of the American student. Clinical instruction is essentially a matter of didactic and clinical lectures, with ward rounds. The student graduates, therefore, without much individual contact with the patient. After graduation, in the absence of an interne system, students become assistants in the various clinics, spending their days in the wards, in routine work or research, and eating and sleeping outside the hospital.[11]

In November 1921, George E. Vincent’s memorandum on “the plan of inviting a group of Japanese medical men to visit the United States” suggested some other characteristics of “American medicine.” In his opinion, “American medicine” also featured efficient hospital administration, high-quality nurse training program, and keen awareness of the importance of public health activities. Therefore, inviting the Japanese delegation to America would at least have the following two advantages:

The observation of public health activities in the United States would stimulate similar undertakings in Japan, where an interest, especially in industrial hygiene, is being developed as a result of the rapid growth of manufacturing centers.

American influence is greatly needed in the fields of hospital instruction, administration, and especially the training of nurses in Japan. [12]

With such ambition in mind, the Rockefeller Foundation sent out the invitation to Japan. Plans for Japan’s first official medical commission began to mature in the hands of Teusler, Japanese medical specialists and diplomats, Rockefeller Foundation officials, and medical specialists in American medical schools and institutes. In the long history of US-Japan cultural exchange, the 1923 medical commission was perhaps often outshone by “Help Japan” initiatives after the 1923 Kanto Earthquake, baseball exchanges, and friendship dolls. However, for understanding the medical communication between Japan and the United States in the early 20th century, the commission carried monumental meaning. Upon the return of the six doctors to Japan, reflections increased on Japanese medical practice that was predominantly inspired (if not shaped) by the German model since the 1870s. It marked a vital step towards the promotion of American hospital practice and medical education in East Asia.

References:

[1] “Roku hakase ichigyō no chakunyū,” March 21, 1923, Nyūyōku shinpō, page 4.

[2] Gregg, Alan. Letter to Richard M. Pearce, 30 April 1923. Rockefeller Foundation records, projects, SG 1.1, Series 609 Japan, Box 1, Folder 3, Medical Education Commission. Rockefeller Archive Center.

[3] Uchida, Kōsai. Letter to Japanese consulates in the U.S., 22 January 1923, page 367. Vincent, George, E. Letter to Ambassador Hanihara in the U.S., 12 May 1923, page 383. No. 37 Beikoku rokkufera zaidan no miura hakase shōtai no ken taishō 12 nen. Ref.B12082155400, Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR).

[4] Auslin, Michael R. Pacific Cosmopolitans: A Cultural History of U.S.-Japan Relations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

[5] Greene, Roger S. Letter to Starr J. Murphy, 16 March 1915. Rockefeller Foundation records, China Medical Board, RG4, Series 1, Subseries 1, Box 26, Folder 559, 405 Japan 1914-1915. Rockefeller Archive Center.

[6] Teusler, Rudolf B. Letter to Roger S. Greene, 19 September 1914. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, SG 1.1, Series 609A Japan-Medical Sciences, Box 3, Folder 21 1913-1918, 1921-1923. Rockefeller Archive Center.

[7] St. Luke’s International Hospital, “History,” https://hospital.luke.ac.jp/eng/about/history/index.html. Accessed 28 October 2024.

[8] East View, “The Japan Advertiser Digital Archive,” https://www.eastview.com/resources/newspapers/the-japan-advertiser/. Accessed 28 October 2024.

[9] “A hospital with English-speaking doctors will form an excellent link for men who wish to go to England or America for their post-graduate studies…That old bogey-man who is known on one side of the Pacific as the Yellow Peril and on the other as Race Prejudice can have no place in an institution where men of both races work together for the relief of pain and the advancement of knowledge.” In “The New St. Luke’s,” The Japan Advertiser, 31 January 1915. Rockefeller Foundation records, China Medical Board, RG4, Series 1, Subseries 1, Box 26, Folder 559, 405 Japan 1914-1915. Rockefeller Archive Center.

[10] Greene, Jerome D. Letter to R. B. Teusler. 10 December 1915. Teusler, Rudolf B. Letter to Jerome D. Greene. 4 January 1917. Pearce, Richard M. Letter to George E. Vincent. 19 February 1918. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, SG 1.1, Series 609A Japan-Medical Sciences, Box 3, Folder 21 1913-1918, 1921-1923. Rockefeller Archive Center.

[11] Pearce, Richard M. Report on Medical Education in Japan, page 45. 1921. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, SG1.1, Series 609 Japan, Box 5, Folder 33 Pearce, Richard M. “Medical Education Survey” 1921. Rockefeller Archive Center.

[12] Vincent, George E. Memorandum on plan of inviting a group of Japanese medical men to visit the United States as guests of the Rockefeller Foundation, 16 November 1921. Rockefeller Foundation records, Projects, SG 1.1, Series 609A Japan-Medical Sciences, Box 3, Folder 21 1913-1918, 1921-1923. Rockefeller Archive Center.