Despite its infamy as a “show about nothing,” Seinfeld’s “Junior Mint” (1993) episode is emphatically about medicine—medical knowledge, the medical world, medical “miracles”. More specifically, it centers on how the ‘general population’ receives medical knowledge. Interwoven subplots caricature the routes through which information about the body’s illnesses and healings pass into what we might call outside, “non-medical” channels. In the 22-minute runtime, Jerry and his friends display how they learn about medicine from late capitalism’s favorite platforms: advertising, commodity consumption, and television edutainment. These are familiar platforms for many viewers; relatable (if not entirely reliable) sources of information. What might that familiarity—identifying with characters who absorb information from informal popular media—tell us about how medical learning works in the American public sphere?

The show is famous for braiding relatability with idiosyncrasy. Jerry’s stand-up comedy sketches at the start and end of each episode rely on being relatable to viewers. Full of “have you ever…?” “you know?”, “what’s with…?”, “you ever notice…?”, rhetorical questions punctuate mundane observations, drawing the audience into a sense of collective common experience. In the narrative episode in between his stand-up, Jerry, Elaine, Kramer, and George alternately body forth and extinguish that relatability. They toggle between being representative of the ‘general population’—when defined as young, white, mostly male middle class New Yorkers finding their way through life’s banality—and acting in absurd, esoteric ways, most often through exaggerated selfishness. In “The Junior Mint,” Jerry and Kramer join medical students in a hospital operating theater to watch one of Elaine’s ex-boyfriends, Roy, get a splenectomy. Kramer jostles for a better view, even “psst!”-ing the surgeon to move out of the way. Mid-surgery, Kramer pulls out a box of Junior Mints and starts snacking. He offers them to Jerry, who pushes Kramer’s hand away in refusal, sending a single candy careening in slow motion and plummeting into Roy’s open surgical site with a light “splat.” Unnoticed by surgeons, assistants, and med students, the Junior Mint gets sewn into Roy. In the coming days, Roy develops a life-threatening infection; Jerry and Kramer panic. But miraculously, Roy’s condition takes an inexplicable turn that confounds his doctors and leads to his full recovery. The episode at first seems like an extreme exaggeration; it’s solidly on the absurd caricature side of the spectrum to imply a chocolate-coated candy cured Roy. It’s completely unrelatable. But in its images and objects, the episode stages the transmission of medical knowledge in more familiar, popular, and relatable ways.

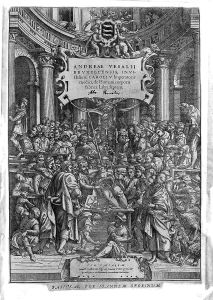

The image of Jerry and Kramer agitatedly staring down from the operating theater echoes an older form of popular edutainment in Western medicine: the public dissection. Seventeenth-century London was home to “supposedly scholarly anatomies,” where members of the public were invited to view the dissection of executed criminals (Nunn 2). The spectacle was simultaneously education, morbid entertainment, and exercise of State power (they proved to be a formidable deterrent of crime) (ibid). According to Hilary Nunn in Staging Anatomies (2005), the atmosphere of these performances “dissolved into the festive spirit of the banquet hall” (ibid). Like Kramer, spectators would eat, shout, jostle against each other. Crowds arrived without strictly educational intentions and, like Jerry and Kramer, likely left without having learned much “medical knowledge” either. But still, public seventeenth-century dissections and twentieth-century operating theaters on “Seinfeld” trace a broader history of popular medical education in the West as casual, rowdy, pedagogically hazy, and like the show, highly social. And while most Americans in the 1990s weren’t watching live dissections or surgeries, they were getting a similar style of education in film and television.

Kramer gets invited into the operating theater because he asks Roy’s doctor what he knows about “interabdominal retractors.” Now, it’s not out of character for Kramer to have the esoteric knowledge to ask a question like this, but here we find out his information isn’t coming from training or research, but from a popular edutainment TV news show:

KRAMER: What do you know about interabdominal retractors?

DOCTOR: Are you asking because you saw “20/20” last night?

KRAMER: I sure am.

Here again we see a balance between caricature and relatability. Kramer is eccentric enough to ask a doctor so patronizingly about something he barely knows about, but relatable in that his information comes from a show that over 14.3 million people watched between 1992 and 1993 (Brooks & Marsh). In an institutional environment where patients often feel disempowered, television programs like “20/20” help bridge that knowledge barrier. Having questions to ask, even if they aren’t relevant, can be a relieving and important handrail; an entryway into the conversation. Even despite Kramer’s wacky singularity (and the more serious aversion attached to his character today after Michael Richards’s 2006 racist tirade), his process of learning medical knowledge is admittedly common.

Unlike watching “20/20,” most audiences would probably know not to take the illness narrative in “Seinfeld” as displaying any kind of scientific truth. At first, it seems that any type of candy or snack would have the same narrative effect. It’s unsurprising that it’s Jerry, the show’s tidy stalwart (his apartment always immaculate, iconic cereal boxes lined up like a Mondrian canvas on the shelf), who rejects the Junior Mint. His swatting-away reinforces that candy doesn’t belong in a medical space, no matter what it is. It’s Kramer, the one who cooks dinner in his shower and reeks of the East River, who eats them in the operating room. But still, we might be able to read Roy’s remarkable recovery from the candy-coated implant as something more than just the show’s standard absurdist narrative closure. Thinking specifically about Junior Mints, the idea that a fresh minty paste could stave off infection somehow doesn’t seem so far from believability. It’s the particularity of being a Junior Mint, I think, that implicitly plays on a deeper cultural misappropriation of medical knowledge in the public sphere, of associating mint with cleanliness, and cleanliness with fighting infection.

Here, the Junior Mint candy is emblematic of a slippery grip on medical science; one that marketing and commodity consumption persistently reinforce. Mint’s conflation with hygiene, cleanliness, and sterility is largely an invention of modern advertising, which here teaches a path of loose medical logic. Covering packaging, in paper ads, and on television, mint has absorbed the pseudo-medical hygienic qualities of the products it flavors. These campaigns conflate those hygienic qualities, in turn, with the sterility of modern medical aesthetics.

Mint has been used for medicinal purposes for millennia: King Jammurabi of Ancient Babylonia prescribed mint as gastrointestinal medicine (1800 BCE); the Ancient Egyptian Ebers Papyrus (1550 BCE) calls on mint to aid in digestion and ease flatulence; the plant was thought by Pliny the Elder to relieve headaches and by Galen to prevent vomiting and pregnancy; Western Europeans in the 1500s used mint to stave off poison, help with blood circulation, and kill intestinal worms; and in the 1600s they thought it could “make the heart cheerefull” (Pickering). Many uses; none related particularly to cleanliness or infection. Ancient Egyptians added mint to early forms of toothpaste, and early modern Europeans reinscribed mint into the discourse of oral cleanliness in the 1620s—rubbing their gums with mint powder and rinsing their mouths with mixtures of mint, vinegar, and white wine. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century’s twinned explosions of commodity consumption and germ theory, mint solidified as a ubiquitous figure in the iconography of hygiene in popular culture. As a result, mint entered into the contested discourse of increasingly influential marketing campaigns that were merging corporeal whitening (teeth whitening, skin whitening) with socio-moral whitening, biosocial hygiene, and the enforced political superiority of whiteness.

Mint flavoring never had medicinal purpose. When Pepsodent introduced mint toothpaste in the early twentieth century, the company used mint to mask the flavor of active ingredients like baking soda and to extend shelf life (Hangley). Mostly though, it was a marketing strategy. A foamy, minty experience creates a memorable sensation that links up with the hygienic habit. Starting or ending the day without a “fresh” feeling in your mouth reminded you that you hadn’t brushed your teeth—you were still ‘dirty’ (ibid). Mint is still the overwhelming favorite oral hygiene flavor in the United States. Listerine replaced menthol flavor mouthwash with “Cool Mint” flavor just one year before “The Junior Mint” aired, and it remains the company’s best seller to “kill germs that cause bad breath” (Hangley, my emphasis).

The Junior Mint, with its iconic red blood cell shape, participates in medical iconography, even if very implicitly. In the cultural lexicon, mint has taken on the properties of the abrasives, fluorides, and detergents responsible for the clean feeling of toothbrushing. In the sterile operating room, “The Junior Mint” episode invokes this slippage between flavor and hygiene. While Junior Mints don’t advertise any hygienic value, they nevertheless are embedded in this pseudo-medical chain of associations. They participate in the idea that clean does, in fact, have a taste. And the best way to fight infection is of course, to keep it clean.

The influence of commodity consumption in creating mint’s image of health saturates the episode even to the final dialogue. As the doctor comes in to check on Roy’s miraculous healing, Kramer shamelessly offers him a Junior Mint. In the original script, the doctor refuses, saying, “Never touch the stuff. It will kill you” (Darlin). But Warner Lambert, the company that owned Junior Mints at the time, required producers to change course (ibid). In the show that aired, the doctor delightedly grabs the candy and parrots Kramer from earlier in the episode: “Those can be very refreshing!” The boundaries between paratext and diegesis blur as the candy becomes both a marketing ploy for the company and a narrative plot device. The doctor’s approval reignites the faint logic of Roy’s recovery-by-candy-implant; it emphasizes an absurd yet culturally legible possibility that the candy did in fact save him.

In two subplots of the episode, Jerry, George, and Elaine all exhibit a similar kind of hazy medical knowledge that is simultaneously individual to their own quirks and shared by broader publics. George confuses Florence Nightingale (English reformer credited with founding modern nursing in the West) with Clara Barton (American Civil War nurse and founder of the American Red Cross), Jerry seems to only be able to name a few female body parts, and Elaine conceptualizes illness as an aesthetic perk—“you get to lose weight!” The show draws parallels between George’s jumbled history of medicine, Jerry’s blasé and misogynist anatomical knowledge, Elaine’s shallow insensitivity to medical narrative, and Kramer’s nonchalant Junior Mint biohazard. Together, the episode positions all three characters on the wrong side of a knowledge barrier, the wrong side of a medical / non-medical divide. But none of it seems to really matter to them.

Is this the fault of their caricatured selfishness—their rejection of considerate sociality, compassion, or care to understand a world beyond themselves—or does the relatable familiarity of the show’s medical discourse diagnose this hazy transmission as endemic to a broader public? As relatable? In this Comedy of Manners (Pierson) in which the characters continually wade through social blunders, is their relationship to and understanding of medicine just another mishap or is it instead a more poignant commentary on the state of medical communication in late capitalism? If the latter, what assumptions is the show making about the impenetrability of the medical world, the ineptitude of popular modes of medical learning, or the power of commodity culture over and above the agency of consumers to inform understandings of health and wellbeing?

To close, I’ll just leave this here: Andy Robin, writer of the episode, later left Hollywood to pursue a career in medicine (Robins). He is currently a psychiatrist.

Images

“Nabisco Junior Mints Commercial 1985.” Posted by Bobby Cole, 27 Feb. 2017. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dv2mcbtQngk.

“The Junior Mint.” Seinfeld, created by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld, season 4, episode 19, West-Shapiro/Castle Rock Entertainment, 17 Mar. 1993. Amazon Prime, https://www.amazon.com/gp/video/detail/B0777X6WKN/ref=atv_hm_hom_c_ondcaM_2_1?jic=8%7CEgNhbGw%3D.

Vesalius, Andreas. De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. 1555, Wellcome Collection (Public Domain). Accessed 12 Oct. 2023. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/mv74d54w.

Works Cited

Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle. The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows 1946-Present (Ninth Edition). Ballantine Books, 2007.

Darlin, Damon. “Junior Mints, I’m Gonna Make You a Star.” Forbes, vol. 156, no. 11, Nov. 1995, pp. 90–94. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9511027645&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Hangley, Bill. “How Brown Listerine Became America’s Most Trusted Health Product.” Reader’s Digest, Reader’s Digest, 2 Nov. 2022, http://www.rd.com/article/brown-listerine/.

Nunn, Hillary M. Staging Anatomies: Dissection and Spectacle in Early Stuart Tragedy. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016.

Pickering, Victoria. “Plant of the Month: Mint.” JSTOR Daily, JSTOR, 1 Apr. 2020, daily.jstor.org/plant-of-the-month-mint/.

Pierson, David P. “A Show about Nothing: Seinfeld and the Modern Comedy of Manners.” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 34, no. 1, Summer 2000, pp. 49–64. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.proxy.uchicago.edu/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2000.3401_49.x.

Robins, Andrew E. “Back to School, after a Career in Comedy.” Medscape, 11 Feb. 2010, http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/716412?form=fpf.

Silva, Henrique. “A Descriptive Overview of the Medical Uses Given to Mentha Aromatic Herbs throughout History.” Biology vol. 9,12 484. 21 Dec. 2020, doi:10.3390/biology9120484.

“The Junior Mint.” Seinfeld, created by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld, season 4, episode 19, West-Shapiro/Castle Rock Entertainment, 17 Mar. 1993. Amazon Prime, https://www.amazon.com/gp/video/detail/B0777X6WKN/ref=atv_hm_hom_c_ondcaM_2_1?jic=8%7CEgNhbGw%3D.