Flesh and bone, bodily hair, tissues, liquids, skin and nerves. For the experimental filmmaker Barbara Hammer (1939-2019), a pioneer in the disruption of heteronormative cinema, the body became a matter of experience and experiment throughout her life. As a person who dedicated her life to making “invisible bodies and histories visible” (Hammer 2010), Hammer attended both the sexuality of women’s bodies and the erotic bonds between them. As scholars like Ara Osterweil (2010) and Rizvana Bradley (2018) pointed out in recent years, and as her final and posthumous exhibitions, Evidentiary Bodies (2018) and Barbara Hammer: In This Body (2019) respectively, attest, Hammer also paid attention to the ill, aging and dying female bodies. Although the medical texture of her oeuvre deserves elaborate attention, within the scope of this essay, I want to engage with one of her earliest –perhaps the earliest in its intensity– films stitching cinema and medicine together.

Hammer’s 16mm film Sanctus (1990) is the result of an archival chance encounter. Upon her arrival at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, housing one of the oldest photography museums and the film archives, with a group of filmmakers, Hammer noticed an unopened 35 mm film can labeled “Watson’s X-Rays”. Her characteristic curiosity and boldness led her to sidestep the tour and open the can. Holding the nitrate strip to the sunlight, she was immediately struck by the images of moving skeletons. To her surprise, these were the footages of a series of cinefluorography (moving X-ray images) experiments conducted by the radiologist, physician and an obscure avant-garde filmmaker Dr. James Sibley Watson and his colleagues in the 1950s. 19-minute Sanctus ended up being the reworking of these found footages.

Although cinefluorography was a recent technology in the 1950s, X-ray has been a popular and well-used technology since its discovery by Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen in 1895, which coincided with the emergence of two other phenomena, namely psychoanalysis and cinema (Lippit 2005, 5). Especially in the USA, there was a great interest in X-ray and X-ray related research due to the increase in tuberculosis cases in the first half of the twentieth century, and breast cancer starting from the 1950s (Cartwright 1992). X-rays, on the other hand, have been inseparable from cultural imagination as well. Many New York women had their hand X-rays taken with jewelry on their finger following the X-ray of Bertha Roentgen with her wedding ring on (Reiser in Cartwright, 115). Only one year after its introduction, the avant-garde Ottoman journal Servet-i Fünun (The Wealth of Knowledge) covered an X-ray experiment took place in Istanbul, which includes a purse (1896), and as a memorable example, Thomas Mann depicted the patients of The Berghof Sanatorium carrying their pulmonary X-ray cards in their pockets and using them as love token in his novel Magic Mountain (1924).

Although the experiments in the found footage were for medical purposes, it is significant that Watson and his associates’ experiments were subjective, curious, and even fun rather than being objective, precise, serious. Moving X-ray images show skeletons turning around, shaving, hand shaking, putting lipstick on while the experiment itself oscillates between medical research and moving picture spectacle. Although the gender aspect and medical gaze in the footage are clear, Hammer refuses any objectification. Earlier in Sanctus, a woman’s body, especially her breasts, catches our attention. However, Hammer’s camera flickers, shakes, and the film is punctured by Hammer herself, any fixation or a possessive gaze is diverted. Even the close-up of a chest prevents the audience’s gaze from contemplating and penetrating the body, which turns into a recurrent gesture throughout the film. As Ara Osterweil argues Hammer’s interference with the footage not only “obscure the anatomical ‘truth’ that the X-ray footage attempts to reveal,” but also underscores a way “the woman’s body can resist yielding its corporeal secrets to the male gaze that has been authorized to interpret them” (196).

Being very much aware of the screen as a medium of representation, Hammer acknowledges that it can be a mode of imagination as well. Experiments themselves are part of this kind of imagination. With that recognition, Hammer bends this imagination by foregrounding the playfulness of the experiments. Hammer’s editing refuses to degrade the body into a single image or a type. Although X-ray requires a private space to be taken, the movements of the body, whose pace is exhilarated by Hammer’s camera, both reminds the ways in which the private is not separate from the public and takes these bodies from their assumed isolation by breaking away with the solitary feeling of medical space. Through retouching, skeletons interact in several ways as they are grabbing each other’s hands, kissing, drinking and human skeletons are superimposed with more than humans such as with a frog, which might be considered as a tribute to earliest animal X-ray experiments. Hammer underlines that X-ray is simultaneously an element of visual culture as it is a medical technology.

Hammer’s intervention in the past and reconfiguration of it are especially striking as the 1950s correspond to a shift in the perception of the X-ray image in America. As Lisa Cartwright traces it, through public health films and ads, and with the X-ray image’s alignment with photographic optics, X-ray became a “symbol of community health” and a “healthy mode of sexual looking” instead of death in those years (32). Publicization/Exteriorization of the body interior and exposition of vulnerability through scientific display were considered to be the condition of health, which is particularly conflated with femininity. The bodies subjected to X-ray in those films were the “wom[e]n who [are] ‘fit’” meaning “young, conventionally pretty, and joyous having [their] picture taken” (33). Hammer’s vision, on the contrary, refracts medical and male gaze by constantly redirecting its focus, and blurs the contours of the bodies and the distinction between them, as well as that of public-private space by repurposing assumptions concerning bodies into a question. The bodies’ movements as skeletons remind the dance macabre; the fusion of subject-object and interior-exterior redraws the line between life and death by obscuring it. The playful tone and color palette of the film turn its face to the inevitability of death, which is also inscribed in the liturgic sonic field of the film. [1]

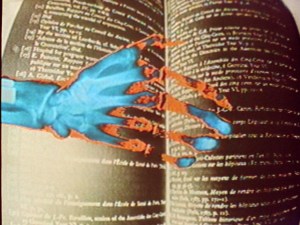

Towards the end, pages of a book flow on the screen with a close-up. The book is superimposed with faintly visible skeletons. Words pass very quickly in front of our eyes while we are able to catch a few words: device-test-cells-clinic-cancer-metas-diagnos. The pace of the scene, similar to that of the score, is so rapid that we must complete some of the words on our own. This verbal interpretation is enacted by the film’s overall inclination to haptic visuality (touch works like the eye) because haptic employment of the sight requires interpretation on the viewer’s part. The page itself seems like a skin on the screen in this encounter. [2] The overall suggestion of the film accumulates in this very moment of porosity between the X-ray image, the body, and the paper. Intimacy with the material, device and the body render the entangled relationship between the body, culture, and medicine visible.

Cover and inside images: Stills from Sanctus. https://barbarahammer.com/films/sanctus/

[1] Sanctus itself refers to a Christian hymn sang in Eucharistic liturgies. However, there is a dissonance between the spiritual tone of the score by Neil Rolnick and the subject of the film concentrating on flash and bone, and the uncanny harmony between the two at times as the music gains tempo with the movement of liquids or skeletons, disrupts the religious discourse by rendering it finite and down to earth.

[2] Here, it is important to remember the close proximity between skin and the film (it is noticeable that pellicule – film in French – also means skin).

Bibliography:

Bradley, Rizvana. “Ways of the Flesh: Barbara Hammer’s Vertical Worlds,” in Staci Bu Shea and Carmel Curtis (eds.), Barbara Hammer: Evidentiary Bodies. Chicago: Leslie Homan Museum of Gay & Lesbian Art / University of Chicago Press, 2018, 56-59.

Cartwright, Lisa. “Women, X-rays, and the Public Culture of Prophylactic Imaging.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 10 (2), 1992, 18-54.

Cartwright, Lisa. Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

Hammer, Barbara. Sanctus. 1990.

Hammer, Barbara. Statement. 2010.

Lippit, Akira Mizuta. Atomic Light (Shadow Optics). University of Minnesota Press, 2005.

Mann, Thomas. Magic Mountain. Trans. by John E. Woods. Everyman’s Library, 2005 (1924).

Osterweil, Ara. (2010). “A Body Is Not a Metaphor: Barbara Hammer’s X-Ray Vision”. Journal of lesbian studies. 14. 185-200. 10.1080/10894160903196533.

Servet-i Fünun. July 2, 1896.