As historians of science, technology, and medicine have long recognized, knowledge about nature does not simply exist in a vacuum of power awaiting value-free discovery. “Colonial science” and “indigenous knowledge” might find themselves occupy the same geographical locality while being politically linked to the “centers” and “peripheries” of a spatially expansive empire (Chambers and Gillespie 2000). To either the utmost innocent or the deliberately intentional onlooker, “traditional medicine” and “biomedicine” may well belong to different temporalities in a narrative about the linear trajectory of history. And there is more. Within the same frame of space and time, an artificially constructed hierarchy of knowledge could also manifest in the hierarchization of materials and non-human life forms. At least, such was the observation of Japanese physician Kagawa Shūtoku (香川修徳, 1683–1755). Much to his frustration, the social stratification of his concern was firmly entrenched by the time his critique made its way into print in 1738:

Medical lineages of the medieval period used the four ingredients ara, kara, aka, and kawa to make what they called a blood-regulating drug, a medication specifically for treating postpartum disorders and women’s blood and qi (ki) illnesses. Aka is akaza. Nowadays both the formula and the method to make it are lost, and rarely is there anyone who knows about it. Occasionally, there are old men from rural areas who teach and use it secretly. Yet physicians nowadays not only pay it scant notice but even view it as a vulgar folk remedy (sōyaku), treating it with contempt and dread. Isn’t that regressive! Little do they know that those four ingredients are far superior to [the four ingredients of shimotsutō]. (Kagawa 1738, 19)

The direct target of Shūtoku’s outspoken indignation was not the social hierarchy of people but the hierarchization of materia medica. The four pharmaceutical substances he held in high regard—ara, kara, aka, and kawa, refer respectively to saw-edged perch (Niphon spinosus), dried chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), an annual plant similar to fat hen (C. a. var. centrorubrum), and East Asian yellow water lily (Nuphar japonica). Among the aforementioned four, only kawa ranked among refined crude drugs per the aesthetics of Chinese medicine, an epistemic standard that Japanese physcians typically consulted if not habitually followed during the Tokugawa era (1603–1868). An extensive corpus of medical texts produced in the literary Sinitic script documents kawa, more formally known as senkotsu, as an integral component of various formulas, including those listed in canonical compilations such as He ji ju fang (J. Wazai kyokuhō), the twelfth-century imperial pharmacopeia of Song China (Chen 1983).

What the Song imperial pharmacopeia also vouches for is si wu tang, the “decoction of four ingredients” pronounced in Japanese as shimotsutō. He ji ju fang classifies the plant-based formula as a prescription for “women’s various illnesses” and recommends it for menstrual irregularities and postpartum complications (Ibid., 741-654). This perception found an audience among Japanese physicians, too. Kaden hihō (Secret prescriptions of family tradition, 1531), a manuscript passed on within the family of aristocrat-physician Yamashina Tokitsune (山科言経, 1543–1611), celebrates shimotsutō as the “chief medicine for women’s ‘way of blood,’” a “blood” disorder known for its subjective and equivocal symptomatology (Kasuo sanmi hōgen 1531, image 28). The erudite physician Katsuki Gyūzan (香月牛山, 1656–1740), who proactively referenced He ji ju fang among other Chinese medical classics in his own writings, similarly acknowledged the prescription as a “fundamental formula for women that regulates menstruation and replenishes blood” (Katsuki 1782, 35 (images 96–97)). Having stood the test of time, shimotsutō now circulates on the Japanese pharmaceutical market as a government-approved OTC formula of Chinese-style medicine (kanpō), indicated for menstrual abnormalities, postpartum and post-abortion fatigue, and menopausal disorders among other health conditions (MHLW 2017, 25).

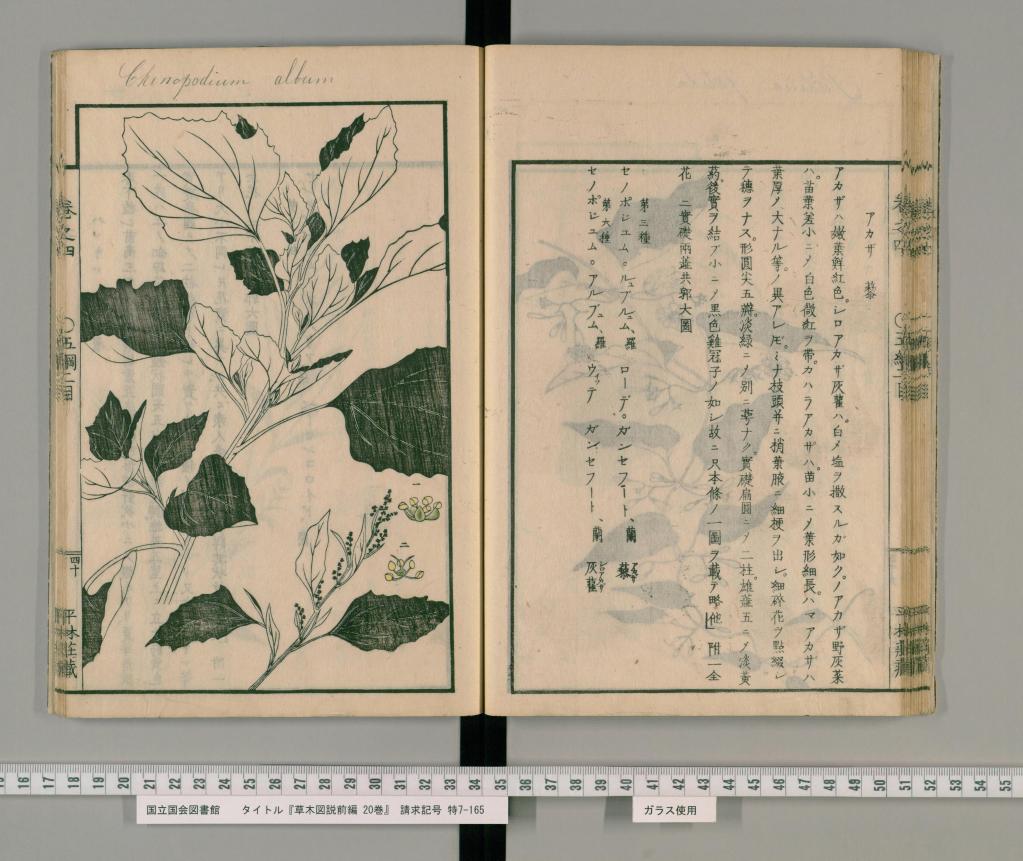

Not all pharmaceutical substances are made equal. Despite Shūtoku’s vote of confidence, akaza, the herbaceous plant illustrated in the featured image, emerges from historical records mostly as a weed: harmless, useful, but nevertheless humble. Nōgyō zensho (Complete works on agriculture, 1697), the treatise of Japanese agronomist Miyazaki Yasusada (宮崎安貞, 1623–1697), outright labels akaza as a “vulgar vegetable (gehin-na na)”:

In China, the broth of akaza is consumed entirely by people who are poor (hin-naru mono). In Japan, those grow in fertile soil are both huge in size and light in weight, and hence make good canes for elders. Although it is a vulgar vegetable, there are poems and essays about it. (Jingū Shichō 1914, 36)

In tune with Yasusada’s observation was the opinion of his contemporary Hitomi Hitsudai (人見必大, c.1642–1701), a physician and scholar of honzōgaku, an intellectual field comparable to natural history. Hitsudai’s publication from the same year Honchō shokkan (Foods of Japan, 1697) describes akaza as a common vegetable that “grows abundantly in the wild and in the gardens of various regions,” the stems of which are edible when young and suitable as canes when old. The plant’s seeds too constitute foodstuff. According to Hitsudai, they were steamed and consumed by yajin—individuals considered rural, rough, if not barbaric (Jingū Shichō 1914, 36).

Associated with the poor and the boor, akaza occupied a lowly place in the hierarchy of materia medica, though not without exception. As alluded to in Shūtoku’s lament at the elitism, ignorance, and historical amnesia already prevalent during his time, Japanese physicians once utilized akaza and other “folk remedy” ingredients with no particular reservation. This open-minded crowd included practitioners of kinsō, a medical subspecialty adjacent to surgical medicine that initially specialized in treating incised wounds caused by bladed objects (Sōda 1992, 5). Amid the political contention and civil war that spanned from the mid fifteenth to the late sixteenth centuries during Japan’s medieval period, kinsō justified its raison d’être by attending to men’s trauma of war and its various somatic and psychiatric complications. Against the same historical backdrop, an adaptive and accessible herb like akaza could have easily stood in as a makeshift remedy when finely prepared crude drugs were difficult to come by on the battlefield. Yet with the enduring peace under the Pax Tokugawa also came a more dismissive outlook on akaza as a weed, a status that the resilient plant seems to carry with it still. When a team of Japanese and Chinese researchers confirmed that the plant received recognition in historical Chinese texts mostly as a vegetable and walking-stick material, their finding received publication in none other than a 2019 issue of the Journal of Weed Science and Technology (Yamaguchi et al. 2019).

What facilitated the historical hierarchization of materia medica more than anything else is perhaps an anxiety about the legitimacy of knowledge. The boundary between kanpō and native Japanese folk medicine was at best ambivalent and permeable. If the urge to enforce authority by upholding the epistemic superiority of canonized textual knowledge over tested practical wisdom had motivated Tokugawa Japanese physicians to disregard akaza, then it was ironically their postwar successors’ fear for exclusion that sustained the same attitude. The Japanese government’s institutional endorsement of Western medical science from the late nineteenth century onward gradually reversed kanpō‘s status. The early twentieth century saw the once mainstream and orthodox system of medicine give way to biomedicine, the new holder of epistemic hegemony. In order to revive kanpō as a field of expertise, postwar practitioners intentionally sought to differentiate it from folk healing. Such was the stance of an article published in the national newspaper Yomiuri shinbun on October 15, 1962, in which kanpō physician Izawa Bonjin (伊沢凡人, 1913–2008) cautioned about the danger of leaving the use of materia medica to amateurs’ discretion in addition to arguing for the distinction between kanpō and folk remedy (Izawa 1962, 9).

I don’t recall if I have ever seen akaza during any of my previous archival research trips in Japan. Perhaps I have walked past one bush on the mountain road of Okayama or in the countryside of Gifu. Or maybe it was hidden in plain sight to my oblivious eyes as I rushed to subway stations in Tokyo and Fukuoka. My personal ignorance and negligence aside, there is no denial that the plant has weathered the vicissitudes of time, sprouting year after year in the shifting landscape of power, and most importantly, it has much insight to offer about the historical logic behind the divergent treatment of medical knowledge and its material reality.

Note: For digitized manuscripts, especially those without fixed page numbers, I provide the location of the cited text by indicating on which digitized “image” the text appears.

Featured Image

An illustration of akaza in a nineteenth-century encyclopedia on plant life: Iinuma Yokusai 飯沼慾斎, Sōmoku zusetsu zenpen, vol. 4, 20 vols. (Kyoto: Izumoji Bunjirō, 1856), https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/2558238/1/45.

Works Cited

Chambers, David Wade, and Richard Gillespie. 2000. “Locality in the History of Science: Colonial Science, Technoscience, and Indigenous Knowledge.” Osiris 15 (1): 221–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/649328.

Chen Shiwen. [12th century] 1983. Tai ping hui min he ji ju fang. 10 vols. Taipei: Taiwan shang wu yin shu guan.“

Ippanyō kanpō seizai seizō hanbai shōnin kijun ni tsuite [On the standard of approval for OTC kanpo pharmaceutical products].” 2017. Pharmaceutical Safety and Environmental Health Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (MHLW). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-11120000-Iyakushokuhinkyoku/0000160072.pdf.

Izawa Bonjin. 1962. “Kanpōyaku būmu to iwareru ga.” Yomiuri shinbun, October 15, 1962, morning edition (chōkan).

Jingū Shichō, ed. 1914. Koji ruien. Vol. Shokubutsu 9. Tokyo: Jingū Shichō. https://dl.ndl.go.jp/pid/897911.

Kagawa Shūtoku. 1731. Ippondō yakusen, zokuhen. Kyoto: Bunsendō. https://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/ya09/ya09_00514/ya09_00514_0004/ya09_00514_0004.pdf.

Kasuo sanmi hōgen. 1531. “Kaden hihō.” Nara Women’s University Sakamoto Ryumon Bunko. https://www.nara-wu.ac.jp/aic/gdb/mahoroba/y05/html/225/.

Katsuki Gyūzan. 1782. Gyūzan hōkō. Vol. 2. Kyoto: Asano Yahē. https://kokusho.nijl.ac.jp/biblio/100268236/.

Sōda Hajime. 1992. “Wayaku no kinsei shi: wayaku no seizai no kaihatsu to wayaku no ryūtsū, saibai wo chūshin ni.” In The 9th General Meeting of Medical and Pharmaceutical Society for WAKAN-YAKU Abstracts, 5–6. Toyama: Medical and Pharmaceutical Society for WAKAN-YAKU. https://ndlonline.ndl.go.jp/#!/detail/R300000004-I10946634-00.

Yamaguchi Hirofumi, Kubo Teruyuki, Ikeuchi Sakiko, and Lu Yuan-Xue. 2019. “Kanmei ni miru zassō ‘akaza’ no seibutsu bunka-shi [Biocultural aspects of the weedy Chenopodium album complex in Chinese vernacular names].” Journal of Weed Science and Technology 64 (4): 127–39. https://doi.org/10.3719/weed.64.127.