Popular cancer narratives often follow a distinct emotional plot trajectory, tracing patient experiences across the heartbreak of diagnosis, the volatility of treatment regimens, and the ultimate elation of survival or the sorrow of loss. But as Nancy Miller shares in a footnote in her 2014 article “The Trauma of Diagnosis: Picturing Cancer in Graphic Memoir,” one prominent cancer story captured attention precisely because of its unique refusal of such familiar structure. According to Miller, artist David Small’s darkly fascinating illustrated memoir Stitches (2009) pins “the trauma of diagnosis” not as an anchoring premise for the piece, but as a reiterative motif which “emerges in painful installments” (Miller 210). The graphic narrative ostensibly outlines how Small’s early exposure to radiation therapy produced a cancerous growth in the boy’s throat which necessitated the surgical removal of his vocal cord, but the memoir develops this sequence out of chronological order and by way of intentionally fragmented depictions of various modes of suffering in Small’s youth. Indeed, Stitches is as much about the trauma of growing up under parental tyranny and austerity as it is about the trauma of cancer.

Miller’s note that Stitches represents a radical departure from many other cancer narratives through its episodic form and its refusal to open with a diagnostic encounter reflects a definition wielded by medical historian Deborah F. Weinstein in her short essay on trauma in the recently published Keywords for the Health Humanities (2023). She writes, “Trauma implies longevity: while a wound suggests an event, a discrete form of violence and harm to the body, trauma tends to imply a longer-term, perhaps even ceaseless experience” (Weinstein 207). Small’s narrative repeatedly centers visual displays of rage, neglect, loneliness, anxiety, discomfort, and panic that poignantly complement the enormous gash signaling the vocal cord absence with which Small, as a frail child protagonist, must come to terms. In short, the memoir’s visual construction of a nonlinear series of aggravated pains sketches a comprehensive model of embodied trauma that expands the focus of more standard cancer stories on malignancy and treatment.

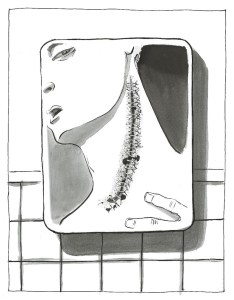

Stitches does, of course, showcase its narrator’s wound site: the gaping and crusted surgical incisions manifest several times in disturbing, full-page scale. Notably, artist and physician Ian Williams, founder of the digital Graphic Medicine site, writes at length on one particularly iconic image in which Small “chooses to render his pain visually by placing the stitched wound at ‘center stage’ and letting his partially reflected face fade into the background” (Williams 120). After the memoir shows Small’s parents and doctors downplaying his operation in their dialogue, the gnarly stitches across the boy’s neck dominate subsequent scenes in grotesque and righteous contradiction.

(190)

(190)

Most of the published scholarship on Stitches, however, searches beyond the throat wound itself to attend to the memoir’s manifestation of the psychologically repressed home landscape in which Small came of age in the 1950s. For example, Leigh Gilmore and Elizabeth Marshall suggest that the graphic memoir reveals how traumatic knowledge emerges in graphic adolescent literature in controversial ways; Ilana Larkin assesses Small’s acquired bodily trauma through the eerily blank eyes of his parents; and Yvind Vgnes addresses trauma and narratology through the overwhelmingly silent images of Small’s household, to name just a few reviews. Clearly, representations of “trauma” beyond—but ever in relation to—Small’s navigation of medical concerns and the event of his tumor excision steer the memoir.

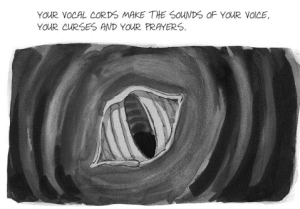

When I assigned an excerpt of Stitches for a graphic medicine unit in the health humanities college course I instruct, my students were compelled by its haunting images. Like many of the memoir’s readers, they noted Small’s construction of creepy grins and hollow eyes for adult characters, the cacophony of sound words juxtaposed with Small’s own voicelessness, and the greyscale images of his immense throat scar which range from hyper-realist to deeply minimalist. But they also observed astutely a set of secondary, visually repeated themes that accompany the more abstract scenes of Small’s difficult childhood: swirling vortexes, crashing waves, and smoggy clouds.

(165)

(165)

(123)

(123)

(19)

(19)

If Weinstein’s definition of “trauma” entails longevity and perhaps even ceaseless harm, then the tumbles Small’s character endures through bottomless, spiraling backgrounds and within the pummeling tidal waves of his mother’s fury constitute an important graphic technique of representation in which “the concealed… can be revealed by the comics artist using various devices, including metaphor” (Williams 125). The memoir has little to do with natural disasters, though the haze present in each of Small’s drawings of Detroit and in cigarette clouds filling the hospital hallways invokes the yet-unforeseen harms of mid-century scientific practices and industrial exposure which contributed directly to Small’s cancer. Nonetheless, the environmental imagery deployed in Stitches helpfully insinuates the constant sensation of falling or drowning or choking owing to external natural forces. Importantly, the vortex, wave, and fog motifs pop up in different places across the memoir such that the multiple sources of harm in Small’s childhood appear layered, symbolically mixed together.

For example, we can notice the all-consuming shape of a spinning cyclone in several places in Stitches: in a cut vocal cord illustration (183), in an x-ray of a plastic figurine caught in another child’s stomach (28), in response to one of Small’s mother’s tirades (47), in a frightening dream episode (45), in the rounded contours of an anesthetic face mask (164), and in a scream the boy imagines himself emitting toward the memoir’s end (234). The trauma of Small’s childhood is expressed not only in the violent, scenic events of household confrontations or his medical disfiguration as contained in individual panels, but also through the repeated convergence of these domestic and clinical encounters through the motif of powerful, cyclical disaster.

(183)

(183)

(28)

(28)

(46)

(46)

(47)

(47)

(45)

(45)

(164)

(164)

(234)

(234)

Stitches thus conveys through visual metaphor what David Small, as an ill child in a stifling home environment, cannot verbalize physically about the compounding pains of his cancer treatment and his parental treatment. If, as Francesca Brencio writes in Metaphors and Analogies in Science and Humanities, “the limits of language and world are a kind of mirror of how we think, how we act, and how we express emotions,” then here, the representational forms made available in autobiographical comics are uniquely capable of plumbing the depths of such limits (333). Small’s character is largely silent in the narrative, but through the images of foggy overlays, the menacing white caps of a tsunami lurking at his mother’s back, the furious whirlpools into which he plunges, and the endless ringed tunnels depicting Small’s hacked throat and his entrance into anesthetic oblivion, the graphic memoir presents an alternative mode of shaping identity, experience, and memory outside of textual language. Ian Williams says that comics thus offer “a way to reconstruct the world, placing fragments of testimony into a meaningful narrative and physically reconstructing the damaged body” (Williams 119). The damages to the body, in Small’s case, are rendered inseparable from the damages to his psyche, as both are heralded by repeated, graphic alignment with destructive natural forces that shape his environment. Nancy Miller suggests likewise that by figuring “the extreme with the everyday, the minor with the catastrophic,” graphic health narratives are able to express trauma anew, “hold[ing] together on the page what the mind tends to keep apart” (210).

If the urgency with which my pre-medical students wished to discuss the waves, gyres, and hazes present on many pages in David Small’s Stitches is any indication, we can extend physician and writer Rafael Campo’s argument that “doctors are well positioned to appreciate poetic metaphor” to include the realm of the visual (1392). Campo imagines the movement between ideas enabled by metaphors as similar to the journeys providers take with patients across stages of life and illness. In Small’s memoir, icons of catastrophic harm—both acute and long-lasting—materialize the sublimated traumatic connections between the boy’s cancer and his turbulent childhood. Stitches may be memorable for its singular displays of medical encounters and domestic screaming episodes, but the visual metaphors of natural disasters help express, build upon, and connect Small’s physical and affective experiences in ways that enhance our understanding of how childhood trauma—externally-induced, “ceaseless,” and often resistant to memory and language—actually unfolds. As a generative sampling of the creative affordances of graphic medicine, Stitches demonstrates how visual metaphors don’t simply supply poetic language; they define and refine our conceptual tools for understanding bodily experiences.

Works Cited

Brencio, Francesca. “From Words to Worlds: How Metaphors and Language Shape Mental Health.” Metaphors and Analogies in Science and Humanities, Springer, 2022.

Campo, Rafael. “Metamorphosis, Metaphor, and Medicine.” JAMA, vol. 330, no. 14, 2023, p. 1392.

Miller, Nancy. “The Trauma of Diagnosis: Picturing Cancer in Graphic Memoir.” Configurations, vol. 22, no. 2, 2014, pp. 207-33.

Small, David. Stitches: A Memoir. W.W. Norton, 2009.

Wienstein, Deborah F. “Trauma.” Keywords for Health Humanities, NYU Press, 2023.

Williams, Ian. “Comics and Iconography of Illness.” Graphic Medicine Manifesto, Penn State Press, 2015.

Header image is the cover artwork from David Small’s memoir Stitches (2009).