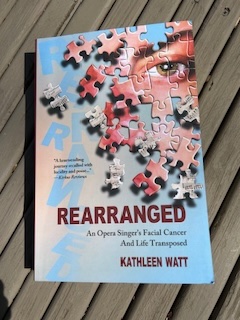

“Don’t be afraid of the blood and guts,” Kathleen Watt smiled while signing a copy of her book: “there are many entry points.” Watt, a former New York City opera singer, was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive cancer that initially filled the space behind her right cheekbone and continued to spread—“occupying the space where my high notes resonate” (51). Rearranged: An Opera Singer’s Facial Cancer and Life Transposed (2023) begins with Watt’s diagnosis in 1997 and chronicles how “the drama of catastrophic diagnosis subsides into a long slog of problem solving…” (56). She had no idea then that “drama” would include more than 30 surgeries over a 10-year timespan.

More than 25 years later, in March of 2024, Watt is in Omaha, Nebraska, discussing her book with Mark Gilbert, a local portraiture artist and professor, whose artistic and research subjects have included patients with head and neck cancer (Gilbert et al.). They are introduced by friend and colleague, Dr. William Lydiatt, a local head and neck surgeon whose research interests include the health humanities. The confluence of these speakers—a patient-artist, an artist-professor, and a head and neck surgical oncologist—provides a rich foundation from which to mine those entry points that underscore the complex intersectionalities between patient, health care worker, and artist.

Recreating her story after many years, Watt utilized “primary documents,” the scratch pad messages from the days she had a tracheostomy, all saved, and the meticulous bedside journals kept by her family. Her writings reveal a pathway toward her own patient-centered care, her reliance on metaphor to help with processing, and the importance of time-stamping an illness story.

Watt begins with a depiction of the anatomy of the head and neck that could be found in any medical textbook, except for the titles, which include: “The human singing mechanism side view,” or “The cranio-facial bones of the skull: A resonant sounding board that amplifies the speaking or singing voice.” Framing anatomy through Watt’s eyes, Rearranged is a patient-centered playbook in how to care for her and reminds health care workers that treatment plans should be filtered through a patient’s perspective. She continues to speak to her patient experience during her first hospitalization by showing how hard it was to maneuver a bedside tray table (114), hold the suction for her trach (97), and bear her frustration over the lack of investigation into her delirium (149-150).

Her use of metaphor is also highly patient-specific. For Watt, the metaphor of patient as performer was an instrumental coping strategy. Before her first surgery, she mused from her gurney: “…closing my eyes in a last lightheaded tumble toward the main stage at the end of the hall, the sensation felt viscerally familiar…costumed, poised to go on, and no way not to. I had learned my part..I hovered between lights down and curtain up. I was ready” (77-78). In Illness as Metaphor, Susan Sontag notably issued a condemnation on the use of metaphor in illness discourse. Since then, others have argued that the use of metaphor by patient and provider requires recurrent and nuanced appraisal, even the oft-cited war metaphor often employed in cancer (McEachem, 601-602).

Contextually, Watt’s story should also be looked at within the social, economic, and medical climate of the mid-1990s, a time when Watt and her partner, Evie, stressed over the recognition of same-sex partnerships for insurance benefits. And although jarring and in poor form, one of her doctors disclosing health information to an outside family member (52) occurred several years before the 2003 Privacy Rule came into effect under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), (Alder, par. 4). Similarly, I willed my own biases to penetrate the time capsule of her illness. As a palliative care clinician, I tried to rearrange her story, shift it a decade or two later, as the field gained more traction, my own hubris guiding a shadow narrative that a palliative care team could have softened her suffering.

While palliative care more commonly accompanies patients such as Watt, unfortunately some sociomedical struggles highlighted by her story continue. At a loss to find a specialist, a call to an affluent and well-connected cousin promptly opened the door for Watt to a speedy referral to a head and neck surgeon, (46-47). Meanwhile, significant inequities still persist for other patients with head and neck cancer. In a recent study of seven clinical trials for head and neck cancer patients, Black participants consistently had worse outcomes than arm-specific White controls (Liu et al. 292).

While time offers its own contextual flavor to an illness story, so, too, does the reader, especially the health care worker, who brings their own filter to the vulnerable interface of an illness memoir. One reviewer, an ear, nose and throat surgeon in training, declared Rearranged a “wonderfully positive memoir” (Reid, par. 1). Perhaps this categorization is a self-protective reflex. After all, Watt’s story details the loss of her singing career, frequent postoperative complications, ruminations on her parents’ illnesses and deaths, fractured relationships, employment insecurity, bouts of depression, insurance insults, and heavy drinking. When she showed some of her writing to her surgeon he responded, “Kathleen, I can’t read about your pain” (Watt, 330). Although he could diligently and repeatedly operate on her for hours, he buckled at the knees after absorbing just a few reflective sentences.

Conversely, when a physician or health care worker eschews suffering, it may be the artistic community that is called upon to notice, to look clear-eyed and unflinchingly at a patient whose illness and story is reflected in facial disfigurement and an ongoing re-negotiation of interpersonal relationships: “But even for non-singers,” Watt wrote, “the face is the single most important organ of human communication. The face, independent of vocalization, is both a signal transmitter and signal receiver…” (105). Earlier in his career, Gilbert, while an artist in residence at two hospitals in London, created a collection of paintings of patients with head and neck cancer called “Saving Faces,” an exhibit which has toured extensively throughout the UK, Europe, and the United States (“Saving Faces”). “I was probably dealing with some of the most highly charged images that any artist could hope to work with, and it was quite disconcerting,” he said in an interview with The New York Times. “But many things I thought they’d find upsetting or distressing, that they’d rather not focus on, I found turned out to be the exact opposite.” (Lyall, par. 8). It is no wonder that through this work Gilbert eventually met Watt and the two became friends.

During her talk, Watt read and even sang—with the help of her prosthesis—through an early chapter that straddled the time between biopsy and a diagnosis revealed via an absurdly inappropriate voicemail from an oral surgeon (40). From this moment of initial overwhelm, Watt unfailingly displays a questioning sensibility. Curiosity drives her story and authenticity fuels a narrative that is singularly hers—her particular evolution as an interpretive artist (singer) to a creative one (writer/memoirist) through her serious illness arc (Watt author talk). In the process she is so generous with grace notes and entry points. Whether a patient, healthcare worker, or artist, she invites all to witness her story: while surgery removes tumors and chemotherapy cocktails eradicate cancer cells, the stamp of serious illness inserts itself into one’s DNA and takes root in the psyche. Body and soul certainly rearranged.

Works Cited

Alder, Steve. “HIPAA History.” The HIPAA Journal, 31 Dec. 2023, https://www.hipaajournal.com/hipaa-history/

Gilbert, Mark A et al. “Portrait of a Process: Arts-based Research in a Head and Neck Cancer Clinic.” Medical Humanities, vol. 42, no. 1, 2016, pp. 57-62. doi:10.1136/medhum-2015-010813

Liu, Jeffrey C et al. “Racial Survival Disparities in Head and Neck Cancer Clinical Trials.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute, vol. 115, no. 3, 2023, pp. 288-294. doi:10.1093/jnci/djac219

Lyall, Sarah. “Painting What’s Left of Faces, Sometimes What’s Behind.” The New York Times, 3 April 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/03/arts/painting-what-s-left-of-faces-sometimes-what-s-behind.html?searchResultPosition=3

McEachern, Robert W. “We Need to Talk About War Metaphors in Oncology.” JCO Oncology Practice, vol. 18, no. 9, 2022, pp. 601-602. doi:10.1200/OP.22.00348

Reid, Jeremy. “Rearranged: An Opera Singer’s Facial Cancer and Life Transposed.” ENT & Audiology, 4 Mar. 2024. https://www.entandaudiologynews.com/reviews/book-reviews/post/rearranged-an-opera-singer-s-facial-cancer-and-life-transposed

“The Saving Faces Art Project.” Saving Faces. The Facial Surgery Research Foundation. Accessed 31 March 2024. https://savingfaces.co.uk/our-mission/art-project/

Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1978.

Watt, Kathleen. Rearranged: An Opera Singer’s Facial Cancer and Life Transposed. Heliotrope Books, 2023.

Watt, Kathleen. “Rearranged: An Opera Singer’s Facial Cancer & Life Transposed by Kathleen Watt, in conversation with Mark Gilbert, Ph.D.” Author talk at Kaneko, 29 Mar. 2024. Omaha, Neb.