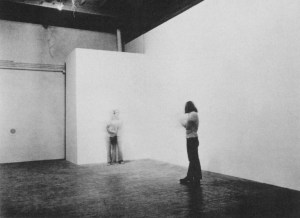

In 1971, a crowd of ten people congregated after hours in an art gallery, F-Space in Santa Ana, California. They were there to watch the artist, Chris Burden, get shot. The bullet was supposed to only graze his arm, but it produced a slightly more severe injury. The few materials that record the November 19, 1971, performance art piece are pared down. In a deadpan note, Burden writes that “At 7:45 p.m. I was shot in the left arm by a friend. The bullet was a copper jacket 22 long rifle. My friend was standing about fifteen feet away from me.”[i] In this note, Burden doesn’t address how it felt to be shot, nor who his friend was who did it.

If Burden felt fear, he didn’t mention it. Most likely he didn’t want to be remembered for the fear he felt before getting shot, nor the surging pain he felt afterwards. As though caricaturing Hemingway, the only detail worth mentioning in this expository note is the type of bullet that injured him. Even this note is performative: the dramatic tenor of what was a hyper-engineered moment of sanitized violence is undercut by this calculated nonchalance.

Burden was performing the spectacle of violence he saw on television: a performance of a performance. He was knowingly tapping into the collective American fascination with gun violence in the wake of the televising of the Vietnam War. Television led newspapers about 64% to 50% when the Roper Organization for the Television Information Office took a survey in 1972, asking where people “got most of their news from.”[ii] War was stripped of its glory in the wake of its televisation: the squalor and violence became more apparent in televised news clips than it might ever have been in print. Burden was aware of this type of voyeurism and spectatorship, the complicity involved in watching someone else suffer through a screen or in an art gallery. Nonetheless, the art piece has not aged well.

Guns in the United States are a part and parcel of a public health crisis. Americans collectively own as many as 400 million guns, and they are accountable for 50% of the world’s civilian-owned guns.[iii] The United States is currently the only country where guns are known to be the leading cause of death among children and adolescents[iv] and there have been attempts to mitigate this crisis by “curing” violence through a public health approach, in part by considering the transmission of attitudes toward gun violence to be a communicable disease that spreads.[v]

This is a new lens through which to understand Burden’s piece, which is not simply a critique of the consumption of violence but also indicative of its “contagion.”[vi] Discussion regarding Burden’s piece often revolves around the notion of complicity of spectatorship: his performance is supposed to undermine the viewers’ supposed innocuousness in institutional settings. In his aptly titled book, No Innocent Bystanders, Fraser Ward writes that Burden’s work interrogates what it means to passively consume pain and violence as an observer. However, Burden’s work perpetuates and communicates the spread of a culture that is nonchalant and deadpan about the

violence inflicted by guns, one that is entrenched in gendered notions of masculinity and war.

The disparity between viewership and embodied experience is exaggerated to new heights in Burden’s work. He weaponizes the experience of pain, and the victimization associated with pain, to leverage an institutional critique not just against museum practices and museum-goers, but also all spectators more broadly, in an era in which everyone is always becoming more of a consumer of spectacles.

However, in doing so, Burden also perpetuates the mythicization and glorification of gun violence, a disease that disproportionately targets Burden’s demographic. Research has shown that mass shootings are, quite literally contagious, and intensive media coverage actually drives its contagion.[vii] Sherry Towers researches the proliferation of infectious diseases, such as STDs and Ebola, and plugged the data set of mass shootings into a mathematical model; she found that trends in mass violence follow the same infectious trends as actual disease outbreak.[viii]

Burden’s gimmick, the glorification of gun violence, should be reread given the evolution of the spectacles and discourse surrounding guns: it is no longer only soldiers, or adult artists, who have consented to being shot. Burden says his work is the distillation of Americana and American folkore, and as such, the piece must be reread in terms of the discourse surrounding incessant gun violence in the U.S. today. Burden gave a glib but telling radio interview regarding his work:

Willoughby Sharp: So it doesn’t much matter to you whether it’s a nick or if it goes through your arm?

Chris Burden: No. It’s the idea of being shot at, to be hit.

WS: Mmmmm. Why is that interesting?

CB: Well, it’s something to experience. How do you know what it feels like to be shot if you don’t experience it? It seems interesting enough to be worth doing.

WS: Most people don’t want to get shot.

CB: Yeah, but everybody watches it on TV everyday. America is the big shoot-out country. About fifty percent of American folklore is about people getting shot.[ix]

Burden insists on the essential “American-ness” of his performance, and he isn’t wrong. The prevalence of civilian-owned guns is a fundamentally American phenomenon that no other nation quite replicates. Americans possess an average of 1.2 guns per capita, the most in the world, with Yemen coming in at a relatively distant second.[x] In a certain sense, Burden’s explanation of his performance art piece is as superficial as it is also prescient. He is unaware that his own work demonstrates the intertangled relationship of the media coverage of violence and its systematic proliferation; he saw shootings “on TV everyday,” and decided to stage his own minor rendition of it.

However, it’s important to make a distinction between critique and acknowledgement. Burden acknowledges the centrality of gun violence in American culture; he makes an emphatic note of it in his work, and he makes the violence more apparent and thereby more entrenched in the collective imagination. Burden’s work is not a critique of the consumption of violence, it is further communicating its contagion. Burden contributes to a certain glorification of violence that made shootings in institutional settings (art galleries and, notoriously, radio shows when he performed a terrorist-hostage-hijack situation on an unsuspecting host) possible and even more digestible.

His form of institutional critique is enacted on a much larger, and incomparably more deleterious, scale by mass shooters, who are similarly also engaging with the same tropes that Burden touches on in his work, a glorification that masks strained hegemonic masculinity; in Burden’s case, it was during the Vietnam War, a time during which the precariousness of the male body during times of war was continually on display on television. In the last forty years, since Burden’s performance, the spectacle of gun violence has been transformed: his work now appears tone deaf when TV reports recount the terror of school children who hide under desks while a shooting takes place.

When the topic of his gun wound is broached in an interview, Burden admits that his performance is “small potatoes” compared to what soldiers in Vietnam endure.[xii] This admission shouldn’t grant him absolution. Burden’s rendition of gun violence is contrived and inauthentic: it goes without saying that the excruciating element of gun violence is not only the physical pain but also the trauma of never seeing loved ones again, the genuine horror that comes with facing death. Whereas Burden was shot in a gallery by a friend in front of complying and complicit, perhaps even eager, witnesses, we know also that children in elementary schools and high school students are not afforded the same controlled environment when facing shooters.

The absence of this horror in his deadpan note and in his trite interviews – “Well, [getting shot] is something to experience” – contributes to a peculiar glorification of violence. He became, quickly, mythical. He became known as the artist who shot himself; the New York Times even ran an article on him in 1973 with the headline “He Got Shot For His Art.”

Burden strips this risk and places himself on a pedestal of pseudo-precarity that earned him much notoriety and public interest rarely shown to performance artists. The kind of impenetrable facade of minimalist passivity extends to his note, to his rather glib interviews, to art pieces that are sensational but ultimately speak little to the nature of trauma, resilience, and to the consequences survivors (and their families) actually bear. Burden’s minimalist performance of hyper-engineered nonchalance enforces the mythmaking surrounding violence. That is to say, Burden knows what it feels like to get hit in the arm by a bullet, but he still has no idea how it feels to get shot. Burden’s work isn’t simply a symptom of what would eventually become a larger public healthcare crisis; it is a vector for its transmission.

Works Cited

[i] “Chris Burden: Original Texts 1971-1995,” Chris Burden (Paris: Blocnotes, 1996), n.p.

[ii] Roper, Burns W. “Changing public attitudes toward television and other media 1959-1976.” Communications (1978): 220-238.

[iii] Karp, Aaron. “Estimating global civilian-held firearms numbers.” Small Arms Survey (2018): 1-12

[iv] Goldstick, Jason E., Rebecca M. Cunningham, and Patrick M. Carter. “Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States.” New England journal of medicine 386, no. 20 (2022): 1955-1956

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Peterson, Jillian, and James Densley. The violence project: How to stop a mass shooting epidemic. New York: Abrams, 2021.

[vii] Green, Ben, Thibaut Horel, and Andrew V. Papachristos. “Modeling contagion through social networks to explain and predict gunshot violence in Chicago, 2006 to 2014.” JAMA internal medicine 177, no. 3 (2017): 326-333

[viii] Towers, Sherry, Andres Gomez-Lievano, Maryam Khan, Anuj Mubayi, and Carlos Castillo-Chavez. “Contagion in mass killings and school shootings.” PLoS one 10, no. 7 (2015): e0117259.

[ix] Bear, Liza, and Willoughby Sharp. “The Church of Human Energy: Chris Burden, an Interview.” Avalanche

[x] Karp, Aaron. “Estimating global civilian-held firearms numbers.” Small Arms Survey (2018): 1-12

[xi] Davis, A., Kim, R., & Crifasi, C. K. (2023). A Year in Review: 2021 Gun Deaths in the U.S. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

[xii] Bear, Liza, and Willoughby Sharp. “The Church of Human Energy: Chris Burden, an Interview.” Avalanche