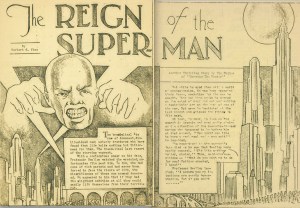

Before he was the square-chested, slick-haired icon, Superman was a villain’s pharmaceutical test subject. In their 1933 short story, “The Reign of the Superman,” Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster (who would later create the iconic Clark Kent comics) describe an evil chemist who goes to the bread-line and indiscriminately chooses one of the many “disillusioned men” to secretly experiment on (1). The chemist promises “a real meal and a new suit,” brings the poor man to his home, and drugs his coffee with a secret “chemical preparation” (1, 2). The chemist, planning eventually to take the serum himself, needed to test its effects on someone else first. The man awakens with extraordinary powers: “I can…intercept interplanetary messages, read the mind of anyone I desire…force ideas into peoples’ heads, and throw my vision to any spot in the universe” (4). “The Superman” leaves the chemist behind and embarks on a rampage, stealing money and predicting gambling outcomes. He kills the chemist just before realizing that the chemical serum’s effects are only temporary. With the chemist dead and unable to replicate the formula, he withers back to destitution and the story ends, “back in the bread-line” (8).

It’s a tale of desperation, nihilistically shattered hope, and violent greed; a not-so-subtle commentary on fantasies of power and moral disintegration under capitalism. There’s also an anxiety around biotechnology: here, evil is both cause and effect of pharmaceutical innovation. When Siegel and Schuster introduce our more familiar Superman in the famous 1938 comic, they replace secretly-manufactured pharmaceutical power with something more “natural.” Superman’s powers come “simply” from extraterrestrial birth—natural and normal for folks there on Krypton. They even hedge his abilities as natural progressions of earthly biology:

“Kent had come from a planet whose inhabitants’ physical structure was millions of years advanced of our own. Upon reaching maturity, the people of his race became gifted with titanic strength! …Incredible? No! For even today on our world exist creatures with super-strength! The lowly ant can support weights hundreds of times its own…the grasshopper leaps what to man would be the space of several city blocks” (Siegel and Schuster, 1938, 1)

Not some pharmaceutical experiment, the 1938 Superman placates anxieties of biopolitical ethics by being, essentially, “all-natural.” In the following decades, more campy characters would arrive on the American comics scene that alleviated fears around the ethics of biotech, self-medicating, and pharmaceutical invention. For example, when the original Ant-Man (1959), shrinks himself with a homemade chemical formula, it makes him a hero, not a villain; stopping crime and thwarting thieves (“Tales to Astonish”). The genre tells us that in the ‘right’ (white, straight, male) hands, self-medicating with one’s own pharmaceutical power is not only a social good, but a hero’s duty.

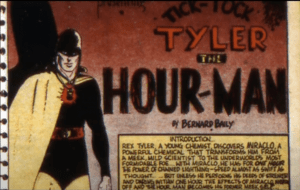

I’m interested in another scientist-turned-superhero of the period, who represents a more explicit connection between gendered power and self-administration of pharmaceutical invention. A chemist by trade, Hour-Man creates and self-prescribes “Miraclo,” a pill* that makes him vaguely superpowered (strength, speed, bravery)—for exactly one hour. His character opens important questions around the issues of gender, autonomy, and surveillance involved in pharmaceutical biopower at mid-century and into our present day.

Hour-Man invokes an idealized masculine image of pharmaceutical self-management. Miraclo gives him conventionally masculine power: it “transforms him from a meek, mild scientist to the underworld’s most formidable foe”—from feminized coward to masculine hero (Baily, 1). Rather than being restricted by his time limit, he becomes a master at management, always aware of how much time is left on the clock. He is an emblem for capitalism’s temporal regime—compartmentalizing, managing, and designating time, controlling one’s laboring body within a structured regimen. Unlike later superheroes of the 1960s onward, whose bodies are unwieldy, unpredictable, and often self-sabotaging, Hour-Man is in complete control. His powers—and his pill—work the exact same way every time. A large part of his appeal as a superhero, I think, is from the fantasy of predictably controlling the body through an autonomy that comes from this specific vision of self-prescribing, self-improving, and self-administering.

Consider this fantasy next to how Paul Preciado’s Testo Junkie (2008) characterizes the development of the female contraceptive pill (“the Pill”) later in the 1950s and 60s. Hour-Man invents Miraclo himself, chooses his timetable, and “designs” his experience of its effects—staging himself at the perfect time and place for heroic intervention. Meanwhile, Preciado cites Patricia Peck Gossel’s study of the 1963 DialPak design to argue that the Pill’s “compliance package” inscribes the hetero husband-wife dyad as a temporal-institutional biotechnology designed to manage the woman’s body, femininity, and time like an “edible panopticon” (195, 173).

Where Hour-Man controls his timed intake of Miraclo, the Pill and its packaging, according to Preciado and Gossel, conscripts the user in an external system of control—and a particular femininity. “It functions,” he writes, “as a device for the domestic self-surveillance of female sexuality, like a molecular, endocrinological, high-tech mandala, a book of hours, or the daily examination of conscience in Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises” (198). For women, Preciado argues, the Pill is a technology of biopolitical (and moral) management:

“…the transformation of the oral contraceptive pill into ‘the Pill’ through packaging can be understood not only as a cultural process that implies social and medical effects but also as a the translation of an architectonic model, a disciplinary system of power and knowledge relationships derived from Enlightenment architectures of the hospital and prison, into a domestic and portable (and later bodily and prosthetic) technique” (201-2).

We can use this comparison to underscore the gendered biopolitical system in which male bodies experience pharmaceutical technology as a way of maintaining and increasing autonomy, control, and biopower, while female bodies are consistently conscripted to surveillance, disenfranchisement, and infantilization by those same biomedical technologies. I find that to be a generative reading of Preciado alongside Hour-Man. But I think we can push farther, too.

Preciado lifts the spandex veil over Hour-Man’s idealized masculinity and autonomy. Hourman doesn’t sense or organically encounter crime to fight, he solicits tasks to help with through an ad in the paper; he never shares his formula with other people who might need it; and he self-medicates entirely in secret, ashamed of his meek “true” self. All, I’d argue, are potential results of compulsory and competitive masculinity in mid-century America. Perhaps it’s not Miraclo but his body and psyche that can’t withstand more than an hour of performing gender so robustly. We could read Miraclo in line with the development of vasodilators (Viagra, Cialis, etc) later in the century; the timed, measured, and surveilled swelling of masculinity’s demands on the body. In other words, Hour-Man offers contextual insights on the history of pharmacological productions of gender in the US that also include the production of pharmaceutical and phallocentric masculinity.

At the same time, Hour-Man might help us better understand possibilities for empowerment and resignification that self-administrations of pharmaceutical gender might make possible. “The fact that the Pill must be managed at home by the individual user in an autonomous way,” Preciado writes, “…introduces the possibility of political agency” (208). Threading back into my previous post on Susan Stryker’s performance-essay, “My Letter to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage” (1994), the mechanization and medicalization of gender is not always or exclusively repressive. How might Hour-Man, even if only partially, embody the (re)enfranchisement of gender-affirming pharmaceuticals, for example, and the autonomy of self-administering them? How might we think with the fantasies that make up this character in a way that amplifies pharmaceutical autonomy and accessibility as the material for new kinds of embodiments, new routes toward agency, and new voices as and with super-powers?

*In Hour-Man’s first comic book appearance, his formula is a liquid serum. From his second appearance onward, the formula has inexplicably changed to pill-form.

Works Cited

Baily, Bernard. Adventure Comics Vol. 1 #48, 1940.

Preciado, Paul B. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. The Feminist Press at CUNY, 2013. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=658634&site=eds-live&scope=site.

Siegel, Jerry. Action Comics, illustrated by Joe Schuster, no. 1, DC Comics, 1938.

Siegel, Jerry. “The Advance Guard of Future Civilization.” Science Fiction, illustrated by Joe Schuster, no. 3, Cleveland, 1933.

“Tales to Astonish,” no. 27. Atlas Comics, 1959.

Images

“Adventure Comics #48 (Hourman Story) Comic Reading.” YouTube, YouTube, 15 Aug. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=viIcuB53VP8.

fengschwing. “Hourman!” Flickr, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Fine, Herbert S. (Jerry Siegel), and Joe Shuster. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Ortho Tricyclen. BetteDavisEyes at English Wikipedia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.