Spidersilk

Towards the end of her memoir, I Cannot Control Everything Forever, Emily Bloom evokes the image of a spider as a way to reflect upon the duality of motherhood. Moving from Ovid’s myth of Arachne through Louise Bourgeois’ giant spider sculpture “Mother of All,” Bloom lands on an investigation into how spiders in nature mother their young. Not all spiders are equally devoted mothers: the black widow will eat her spawn if she must, while the desert spider mother will sacrifice her body, allowing the tiny spiders she laid to eat her up, literally, from her legs to her heart. From these gruesome, extreme forms of mothering—so alien to our human way of doing things, yet temptingly lending themselves to metaphorical parallels—Bloom draws her conclusions in beautiful prose l:

In both cases—the good, self-abnegating mothers and the bad, predatory mothers—the silk for which they are so well known is used in creating webs and egg sacs alike. For these species, the art of weaving is closely connected to the biology of reproduction. The spiderweb is beautiful, deadly, generative. The mother weaves life into and out of the world. Like the Greek Fates, those three goddesses presiding over the looms of destiny, the spider’s weaving is an art of creation and destruction at once. It is merely a matter of what will be created and who will be destroyed. (305)

Herself a master craftswoman, Bloom resists the allure of the “good mother/bad mother” metaphors, shifting her attention instead to the metaphoric potential latent in the spider silk, that precious material created through so much labor and used both for art and for mothering:

I keep writing […] This is my web. It is made of the same stuff that I used to make a life for my child. It is silk: the mother stuff. I don’t know if this makes me a good or bad mother, but I expect that I am a little of each. (310)

Like Bloom, I am a mother to a small child. My daughter was born while I was writing my dissertation, and through those first years, I tended to think of these two forms of care and labor as fundamentally, ontologically, separate: the me who reads and writes and thinks is a wholly other being to the me who feeds and bathes and plays and sings and comforts. Reading through Bloom’s silk metaphor, meeting the idea that both modes of being, both forms of work are accomplished using the same inner resources, the same “stuff,” engendered a minor revolution, making potentially possible the integration of these disparate parts of myself.

Weaving

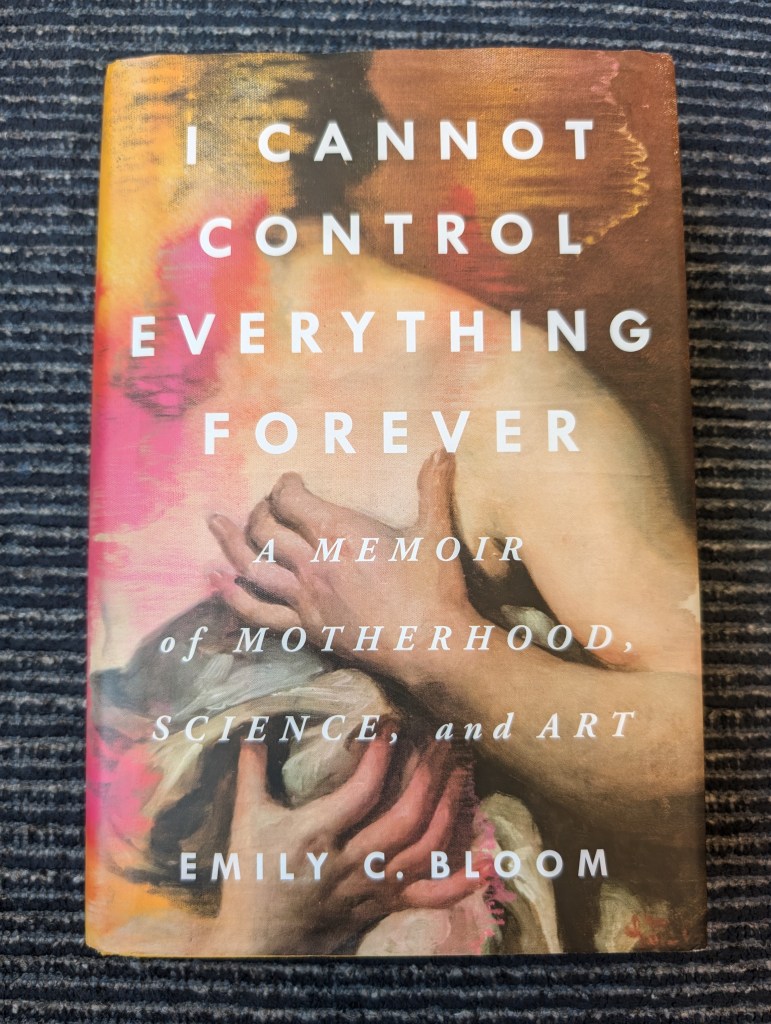

I Cannot Control Everything Forever is the deeply personal story of Bloom’s journey towards motherhood, through multiple pregnancies, and the raising of her daughter Willie from infancy to toddlerhood. It is often painfully intimate and intimately painful: though touched on briefly, and counterbalanced by gratitude, Bloom’s reckoning with, for example, the loneliness of pandemic-era parenthood, and the darkness that follows the loss of a pregnancy, are vividly recounted and hard to read, even as these descriptions eschew emotional gore. So, Bloom does not elaborate on her feelings following the miscarriage; instead, we hear about a teaching demonstration she performed as part of a job interview, following closely after the miscarriage. The effort she put in that demonstration, and the dawning realization of the fact that the job will not be offered, reached into my heart with a sharp stab of sympathy, reflecting back—like light bouncing off of a smooth surface—on the more embodied, more private, loss. The following page tells simply of a dream from months later, in which she tries to feed a baby with a cellphone (41); the horror of that dream made me put the book down for a full day.

But even as the main narrative through-line is predominantly personal and self-reflective, Bloom weaves a complex web of associations, expanding from the experiential to other domains—in science, art, and literature—and follows along these lines of expansion outwards and back to herself, the center of that web. At first, I was thrown off by these tangents, and while fascinated by the information they introduce (the origins of pregnancy testing; the history of Deaf education in the United States), the transitions between the personal and the almost-scholarly were jarring to me. But the more I read, the more I understood that this expansion of the web is in fact part of the argument of the book. The sciences, and histories of sciences, and stories and myths and pictures, are not a separate domain from that of personal history, and by situating her story within this vast net of associations, Bloom refuses an implicit demand to keep motherhood in a separate (female, private, domestic, incommunicable) realm, and foregrounds the ways in which being a mother is an experience interlaced with, and often dictated by, multiple public frames of reference.

Entangled

Even as Bloom constantly expands outwards, from the core experience of “motherhood” to the scientific, historical, and cultural stories that shape it, there is also a pull in another direction – not expanding the web but struggling to escape from it. A question comes up, not fully asked but hovering under the surface of her narration: what would it be like, to have a child, to be a mother, without having this experience so heavily determined by other forces, other stories. This question rises out forcefully when Bloom talks about the scientific standard for “the good mother”:

A good mother is now often defined not only in terms of traditional standards of nurture and care but, increasingly, by the degree to which a parent protects their child from environmental harm and works alongside a medical team to track development and intervene when their child goes off track. (13)

The pressure to conform to a standard of good, “scientific motherhood” (13)—ever increasing as-is with every technological advancement, access to more and more data—this pressure increases exponentially when mothering a child with disability or medical needs. Willie is born with congenital deafness, and diagnosed with diabetes around her first birthday. Her mother vacillates between profound thankfulness for the technologies which sustain Willie, which make her life better, and the impulse to resist, or at the very least question, the extent of technological intervention in their lives.

Bloom is ambivalent towards the networks in which she, as Willie’s mother, is enmeshed. On the other hand, there is nothing equivocal or unsure in her embrace of another network which shapes her life, the connections with people dear to her heart. Late in the memoir, Bloom recounts being asked about her personal connection to disability, having just given a lecture about Teresa Deevy, a deaf playwright.

Disability rippled through my life, but it is also not mine to claim, I wanted to say. I was adjacent to disability, but this adjacency has shaped every contour of my personality and my sense of the world. (225)

The words do not come out as an answer at the lecture; Bloom is hesitant to cross the divides which separate her academic self, and the world that such self occupies, from her other self—the one that is “adjacent to disability” through the people closest to her: her brother, her daughter. This answer-that-would-have-been, meanwhile, lays the foundation for the structure of the memoir, as well as some of its main thematic questions: what are the boundaries between the self and the world? How does knowledge, with its shifting parameters in data and technology, change our conception and experience of those boundaries?

A Proverb

At my PhD graduation ceremony in May, one of the speakers evoked an ancient Greek proverb: a fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing. Earning a PhD means donning a hedgehog’s quills, affirming knowledge of One Big Thing. I Cannot Control Everything Forever is not a hedgehog book; it does not dig deep and narrow, it does not view the world through the lens of one idea. It is also not a fox book, wide reaching as it is in scope. Rather, Bloom’s book demands a revision to this proverb: “The Butterfly knows how things transform,” the proverb-updated-for-the-twentieth-century would go, “but the spider knows how they connect.” A true spider-book, Bloom’s memoir also has the power to help us rethink how knowledge itself is classified, organized, and lived with.