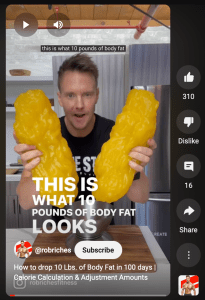

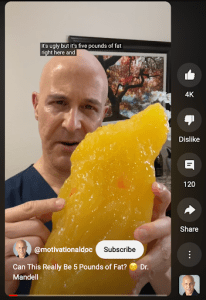

As of writing this, I can buy a 1lb or 5lb silicone “fat replica” on Amazon for anywhere between $29.99 and $139.99. They’re lumpy, brain-like oval shaped masses in an almost glowing yellow, sometimes with small red threads representing blood vessels visible through their semi-opacity. The names of each product link has Amazon’s signature word salad, different combinations of “For Staying Healthy,” “Weight Loss Motivation,” “Keep Fit,” “For Fitness Room,” “Educational Supplies,” and “Model for Nutritionist, Athlete.”

These are pedagogical objects—tools for teaching a seemingly straightforward, simple lesson: this is what that part of the body “really” looks like. Ostensibly, these replicas should be able to serve as teaching tools for any number of lessons on fat tissue, like its role in the endocrine system or its function as a nutrient reservoir. Their Amazon titles evoke a sort of Cubist multiplicity of angles from which to approach the object, together on the flat plane of the product link: “Authentic Human Body Fat Replica – 5lb, Keep Fit & Weight Loss Motivation & Reminder, Human Fatty Tissue Demonstration Model for Nutritionist, Anatomical Science Course for Medical Student.” But these different uses aren’t equal or even distinct. As much work in fat studies has shown, “Weight Loss Motivation” and “Anatomical Science Course” are not easily separable frames. Even in a ‘strictly anatomical’ context, fat tissue often remains sutured to the culturally charged discourse (imperative) of weight loss. “Given the extent to which fatness has been condemned and pathologized over the past century,” writes Abigail Saguy, “it is impossible to choose a truly neutral word”—or here, teaching tool—“for fat” (7). As Kristen Hardy has aptly argued, “it is the very capacity of objects to act as nexuses for the commingling of the abstract and the concrete, the psychological and the material, inner space and outer life, and, in this case, meaning and affect that situates these amber-hued lumps…as valuable aids to elucidating the cultural polyvalence of fat.” Fat replicas are both implicitly and explicitly affective objects absorbing and reproducing cultural lessons around fat tissue; namely, that its visual and/or material presence should spark abjection and action.

Fat replicas contain an unspoken and uniform prescription. They typically have no accompanying materials—no posters, labels, curricula—because the lesson is ostensibly self-explanatory. The learner is always supposed to be repulsed. There is nothing to signal what area of the body it replicates (or why that would matter), how it interacts with adjacent structures, or its variance across bodies. Unlike anatomical models of the heart, lungs, or skull, fat replicas anticipate a specific affective reaction. As they exist in public visual culture and popular modes of medical education like social media, fat replicas teach simply by the shock of the reveal. Like an outdated anatomy class they plainly, “rationally” categorize—this is the heart, this is the knee, this is the fat—but mixed with a jump scare: THIS is what it looks like! Their marketing implies a sort of universal behaviorist trigger; just seeing the object encourages a different behavior or action. In Jay Jacobs’s online “My Pet Fat” diet program, for example, “the purchaser is encouraged to place a replica inside his or her refrigerator to discourage ‘overeating’” (Hardy). Teaching an affective pedagogy of implied repulsion, fat replicas, according to Hardy, are “particularly meaningful and feeling-ful’ cultural artifacts” (Hardy, original emphasis). They visualize fat as a monolith—both in being one cohesive piece and in conscripting only one appropriate response to seeing them. The frame within which the learner is meant to understand a fat replica has already been set by the cultural overrepresentation of fat tissue as “ugly”—something to be removed, feared, and rejected.

Despite their unavoidable materiality, I see fat replicas invoking Kata Kyrölä’s concept of “phantom fat”—lingering, haunting matter that’s perceived as a threat to an imagined future. There are complex and important implications here for feminist fat studies, race studies, and other intersectional studies of the body deserving more space than the scope of this post allows. For now, I briefly focus on “phantom fat” as an example of pedagogy that produces meaning across each of those spaces. I’m interested in the demands implicit pedagogies make on the imagination; how learning the body involves a series of strategies that are material, affective, imaginative; how the objects we use to learn the body transform bodies themselves. Again, the emphatic physicality of fat replicas—their foregrounded texture, their power to produce meaning and action just by being there—might make them seem far from something immaterial like a phantom. But Kyrölä also describes phantom fat in affective and temporal terms:

…the vast majority of mainstream media images of fat bodies make fat into a removable, threatening…almost haunting entity…As such, these images produce an ideal viewer who is expected to fear and reject actual or potential ‘fat’ parts of their bodies, whether ‘fat’ exists in the concrete now or in the imagined future. Thus, the ideal viewer’s body image contains fat as a phantom limb of sorts…feeling as-if real, although not existing in the flesh…for those who experience their bodies as fat, the material reality of fat is made to appear unlivable, enforcing a phantomizing of their lived flesh as if it was not fully material (my emphasis)

As discrete, detached objects, fat replicas literally rehearse the mobility of phantom fat, bodying forth the idea that fat is something that can—and should—be removed. They become screens onto which the ideal learner projects images of themselves across time with anticipatory fear and repulsion. Their embodied teaching strategy is to “haunt” the learner—to linger in their consciousness as they make choices that, according to the logic of their marketing, will either move them closer to or farther away from becoming the replica itself—the replica “feeling as-if real” flesh. There’s a disruption of clear distinctions between the ‘real’ tissue and ‘replica’ tissue. They’re ever-present in cognitive, affective, and physical traces—one Amazon reviewer writes, “it is super wet, sticky, and leaves residue over.” Fat replicas materialize the mobility, anticipatory temporality, and haunting ubiquity of the phantom.

This doesn’t just apply to fat replicas—other “inside views” and “reveals” of fat tissue share this overdetermined phantom pedagogy. For example, in Gross Anatomy cadaver dissection, ‘real’ tissue functions in a similar way. Like the unhappy Amazon reviewer with “residue all over,” the grease of cadaveric fat can “transfe[r]” to students’ “skin and en[d] up as stains” on their clothing and notebooks (Scott-Fordsman). Almost half of Gross Anatomy students in a 2020 study by Goss et al. reported leaving dissection feeling “worry” about their own bodies and “afraid” that they themselves had or would one day have “too much fat.” It lingers and haunts, staying with students both as physical and psychical marks; as a fearful potentiality. They reported “feeling more self-conscious, or feeling worse about themselves.” Again, though emphatically material, cadaveric fat shares “phantom” qualities, hovering in excess of the cadaver and prompting imaginations of the learners’ own bodies on future dissection tables.

All this, of course, takes place beneath the surface of a rational, self-evident ‘reality’ that can obscure the stigmatization so deeply embedded in how we understand and learn from these objects. In cadaver dissection, for example, fat tissue is objectively “in the way” of other, more pedagogically valuable anatomical structures. Since the nineteenth century, Western dissection guides have instructed students to consider cadaveric fat as a detachable substance to be removed and separated—”dug out” and “scraped off”—from other anatomical structures, much like the clean isolation of a fat replica (Weisse 16, 32). But unlike replicas designed to be as one Amazon link harks, “attention-getting,” cadaveric fat is most often removed and stored with other bodily “waste,” separate from the organs that students will re-examine throughout the course. Students’ affective responses to seeing cadaveric fat become confused and entangled with the physical, objective problem of accessing other parts of the body (ignoring the culturally-informed hierarchy ranking pedagogically ‘important’ anatomical structures). In dissection, it’s difficult if not impossible to separate fat tissue as a physical problem from the broader cultural discourse on fatness as a social problem. Similarly, the marketing of fat replicas braid their implied affective charge with claims to rational objectivity—it’s just how it really looks. For both cadaveric fat and silicone fat replicas, there is a pedagogical context that obscures the cultural saturation, the phantom functions.

Here, I want to briefly compare this phantasmatic pedagogy to the type of haunting at work in gothic fiction, a genre known for its play between rational detachment and the affective thrills of the supernatural. This cluster of objects bound by the “phantom”—fat replica, cadaveric fat, and gothic novel—might tell us something, I suggest, about the affective, temporal, and imaginative mechanics of teaching and learning the body. I turn to Ann Radcliffe’s genre-defining gothic novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) to ask what the cultural pedagogies that frame fat replicas and cadaveric fat might share (and not share) with gothic narrative—and what that can tell us about how cultural pedagogies stick to fat.

Radcliffe’s protagonist, Emily St. Aubert, experiences a number of horrors both physical and psychological while held against her will in a gloomy, decrepit castle. At one point, she glimpses behind a black veil hanging on a wall thinking she’ll see a painted portrait. Instead, she finds a recession filled with what she perceives as a rotting corpse. The discovery lingers, haunting Emily throughout the novel. She fears that what she’s seen behind the veil—what’s been graphically revealed to her—will become her own fate. This is the type of anticipation and suspense that charges the plot and gothic fiction more generally—the shocking “peek” that, like the “reveal” of fat replicas, haunts, shapes, and threatens the protagonist.

After hundreds of pages, Emily finally discovers that what she saw was in fact a wax memento mori—an object made to remind the viewer of their mortality. The sculpted model was, like Amazon’s fat replicas, a behaviorist trigger, a “motivating” intervention: “A member of the house of Udolpho, having committed some offense against the prerogative of the church, had been condemned to the penance of contemplating during certain hours of the day, a waxen image, made to resemble a human body in the state to which it is reduced after death” (Volume 4, Chapter 17). Like the fat replica and cadaveric fat, the ideal learner uses this object to imagine their future selves with shock and fear and, subsequently, changes their actions accordingly. The object creates an unspoken and uniform prescription. Not a fantastical vision, these are meant to be harsh realities—this is what it looks like—here, complete with a face “partly decayed and disfigured by worms, which were visible on the features and hands” (ibid). Even with the added worm drama, there is a matter-of-factness that obscures the work of the imagination and cultural meaning-making here—that makes its message seemingly obvious, rational, and inarguably true.

Yet at the same time, the wax corpse also represents an inversion of the affective revelation invoked by fat replicas. In the context of the narrative, the ultimate reveal of the wax figure relieves Emily, calms her fears. In recognizing that this isn’t a real body, only a replica, its threat to her own body is emptied. The object didn’t in fact have power for just showing how it really is, it became a phantom in the context of Emily’s pre-existing suspicions, the caricatured atmosphere, and the work of her imagination. In fact, once Emily sees what the object “really” is, it drops out of her mind and out of the text. And unlike the fat replica removed from its visceral embeddedness to enter gyms and refrigerators, the wax figure stays nestled in the castle wall.

Radcliffe would become known for these rational explanations that account for what at first seem to be supernatural hauntings. Her somewhat anticlimactic explanations reverse the function of rationality as it works on fat replicas and cadaveric fat. There, objective rationalism is a vehicle for powerful affective imperatives, a way of obscuring the stigmatization that drives how they function. Here, the real revelation is that heightened affect obscures and distorts reality—these phantoms aren’t natural, they’re created. Radcliffe’s over-the-top scene-setting defies the naturalized self-evident pedagogy surrounding fat replicas and cadaveric fat. Gothic novels are absorbing, high-camp atmospheric productions, seeping with lengthy descriptions of stormy landscapes and living architectures. Everything is an elaborate construction and each detail from the rafters to the clouds has carefully crafted (often spooky) meaning. It is a highly decorated frame (or, an ominous black veil) that shapes how Emily interprets her experiences and her world, that turns the wax replica into a terrifying and future-threatening vision. It’s through the gothic novel that we might see more clearly the constructions shaping affective learning, hermeneutic architecture that, in the cultural overdetermination of fat tissue, is increasingly implicit.

Works Cited

“Authentic Human Organ Model for Motivation, Demonstration, and Display – Anatomical Nutritionist Teaching Tool.” Amazon, www.amazon.com/Authentic-Motivation-Demonstration-Nutritionist-Anatomical/dp/B07KXLBCNT. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.

Cadaver Dissection,” Medicine, Anthropology, Theory, vol. 9 no. 1, 2022.

Goss, Adeline L et al. “The “difficult” cadaver: weight bias in the gross anatomy lab.” Medical education online vol. 25,1 (2020): 1742966. doi:10.1080/10872981.2020.1742966

Hardy, Katherine A. “The Education of Affect: Anatomical Replicas and ‘Feeling Fat’.” Body & Society, vol. 19, no. 1, 2013, pp. 3-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X12441629.

Kyrölä, Kata, and Hannele Harjunen. “Phantom/Liminal Fat and Feminist Theories of the Body.” Feminist Theory, vol. 18, no. 2, 2017, pp. 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700117700035.

Radcliffe, Ann. The Mysteries of Udolpho. Project Gutenberg, 2008, www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3268. Accessed 13 October, 2024.

Saguy, Abigail C. What’s Wrong with Fat? Oxford University Press, 2013. Scott-Fordsmand, Helene. “Sticking with the Fat: Excess and Insignificance of Fat Tissue in Cadaver Dissection,” Medicine, Anthropology, Theory, vol. 9 no. 1, 2022.

Weisse, Fanueil Dunkin. Practical Human Anatomy: A Working-guide for Students of Medicine and a Read-reference for Surgeons and Physicians, Volume 1, W. Wood, 1888.

Images

“5 lbs of Fat vs 5 lbs of Muscle Comparison.” YouTube, uploaded by Total Fitness Bodybuilding, 19 Aug. 2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=4xNL1MdLQGk. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.

“File:Momento mori in the form of a small coffin, probably Southern Germany, 1700s, wax figure on silk in a wooden coffin – Museum Schnütgen – Cologne, Germany – DSC09943.jpg.” Wikimedia Commons. 25 Jan 2022, 06:53 UTC. 13 Oct 2024, 23:02 <https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Momento_mori_in_the_form_of_a_small_coffin,_probably_Southern_Germany,_1700s,_wax_figure_on_silk_in_a_wooden_coffin_-_Museum_Schn%C3%BCtgen_-_Cologne,_Germany_-_DSC09943.jpg&oldid=624230651>.

“Search results for ‘fat replica.'” Amazon, www.amazon.com/s?k=fat+replica&crid=5PATNVW0GWDQ&sprefix=fat+replica%2Caps%2C148&ref=nb_sb_noss_2. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.

Sears, Matthew Urlwin. Illustration for The Mysteries of Udolpho. 1826, Limbird’s Edition of the British Novelist, London. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, Public Domain.

“Visualizing Fat and Muscle.” YouTube, uploaded by Visceral Dynamics, 6 Oct. 2022, www.youtube.com/shorts/Us3DZeo_iXk. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.

“You Won’t Believe How Much Fat We Carry!” YouTube, uploaded by SimCoach, 6 Oct. 2022, www.youtube.com/shorts/NfozdIus_Ag. Accessed 11 Oct. 2024.