Blood is an enduring metaphor for heteronormative kinship. However, Keiko Lane, author of the new memoir Blood Loss: A Love Story of AIDS, Activism, and Art (Duke, 2024), appropriates the image of blood as a symbol for the queer intimacies forged in coalitional AIDS activism of the 1980s and 1990s. The memoir follows Lane as a teenager in Los Angeles, as she joins activist groups, such as ACT UP/Los Angeles and Queer Nation, and develops close relationships with a cohort of radicals, many of whom are living with AIDS. As one of the bodily fluids through which HIV is transmitted, blood also indexes the risk that many queer people take in leaving their families behind (by choice or by necessity) to form new relations that may be more accepting of LGBTQ+ identities, struggles, and ways of life. In bringing together personal reflection on loss and caregiving, Lane adds a more personal dimension to recent scholarship on queer kinship and queer care ethics.

Lane is a queer, Okinawan American therapist and writer living in the Bay Area whose clinical and written work focuses racial, sexual, and gender justice and experiences living with HIV. Readers may be familiar with her writing on trauma and HIV/AIDS that has appeared in collections like The Feminist Porn Book and Between Certain Death and a Possible Future. Lane continues to write about these themes in Blood Loss but adds a more reflective and personal account to her work as an AIDS activist.

The affective and aesthetic descriptions she offers of meetings for Queer Nation and ACT UP will be familiar to those who have read or watched clips from the ACT UP Oral History Project or read books like Ann Cvetkovich’s An Archive of Feelings, Deborah Gould’s Moving Politics, or Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show. Activist meetings often produced an effervescence in which sexual possibility, optimism, and rage were both palpable and sustaining forces for activism. As Lane writes of her first Queer Nation Meeting, it was like the “mundane and the magical coming together, under the glaring fluorescent lights of the community center” (18). What Lane contributes to the scholarship is her perspective as a teenager. Too often, critical writing on HIV/AIDS has overlooked the fact that AIDS social movements were also a part of queer youth cultures. The normative rites of passage for queer youth—dating, falling in love, coming out, going to college—were emotionally heightened by the fact that Lane and her friends were trying to survive a devastating disease and grapple with sickness, death, and mourning.

The thrust of the narrative is focused on Lane’s friendship with gay men of color, such as the Puerto Rican AIDS activist Cory Roberts-Auli. Along with W. Wayne Karr, Roberts-Auli created the queer AIDS zine Infected Faggot Perspectives (1990-1995), which was typified by its gallows humor and queer sensibility. Roberts-Auli was also a visual artist who created a series of haunting drawings that show the outlines of the human body rendered in his own infected blood. One of these blood drawings appears on the cover of the book, Power in America (Heteros) (1994), which Lane cannot help but interpret as a depiction of her relationship with Roberts-Auli.

After meeting Roberts-Auli at an activist meeting, the pair quickly form a transgressive queer friendship. Lane and Roberts-Auli begin sleeping with each other, and Lane tends to his bloody wounds following a violent encounter with the police during a protest. When Lane goes to get tested for HIV, she remains cagey when asked about her risk behaviors. As a 17-year-old “underage dyke” sleeping with an “HIV-positive fag” in his late twenties, Lane worries that the community health worker may be obligated to file a mandatory child abuse report (61). In the age of #MeToo, many readers may find this relationship suspect, unethical, and even criminal. Lane’s broader point, however, is to show how AIDS activism provided a space to experiment with intimacy and sexual fluidity in ways that were unintelligible in the public sphere.

The climax of the narrative occurs when Lane refuses to give Roberts-Auli pills to end his life on his own terms. Earlier in the book, Lane had agreed to supply the medication when her friend believed it was the right time. Roberts-Auli frames his desire for assistance with suicide as an act of care and friendship: “You want to love me? This is what it means to love me” (47). When Roberts-Auli does finally make this act, Lane freezes as she imagined this moment would be a precise “ritual” couched in “some romantic notion of bravery and nobility and something thought through” (73). Roberts-Auli never quite forgives Lane for what he views as her betrayal, reminding her later that “It wasn’t your decision to make” (199). Lane seems to have lingering guilt about the episode. “I will never not have his blood on my hands,” she writes near the end of the book (273).

Keiko Lane’s Blood Loss opens new lines of inquiry about what lessons the AIDS crisis might teach us about intimacy, “chosen family,” loss, and mourning. The book also makes an important contribution to the history of AIDS social movements by focusing on Los Angeles rather than New York, the setting of most AIDS nonfiction writing. Nevertheless, there are some aspects of the book that leave the reader wanting. The memoir would benefit from the inclusion of images, including artwork, excerpts from Infected Faggot Perspectives, and photographs of ephemeral performances spaces, such as Club Fuck! This is especially important since many of these materials have not been digitized. This minor limitation aside, Blood Loss is an engaging and accessible book that offers a fresh perspective on the history of HIV/AIDS activism and attests to the power of friendship in surviving an epidemic.

Work Cited: Lane, Keiko. Blood Loss: A Love Story of AIDS, Activism, and Art (Durham: Duke University Press, 2024).

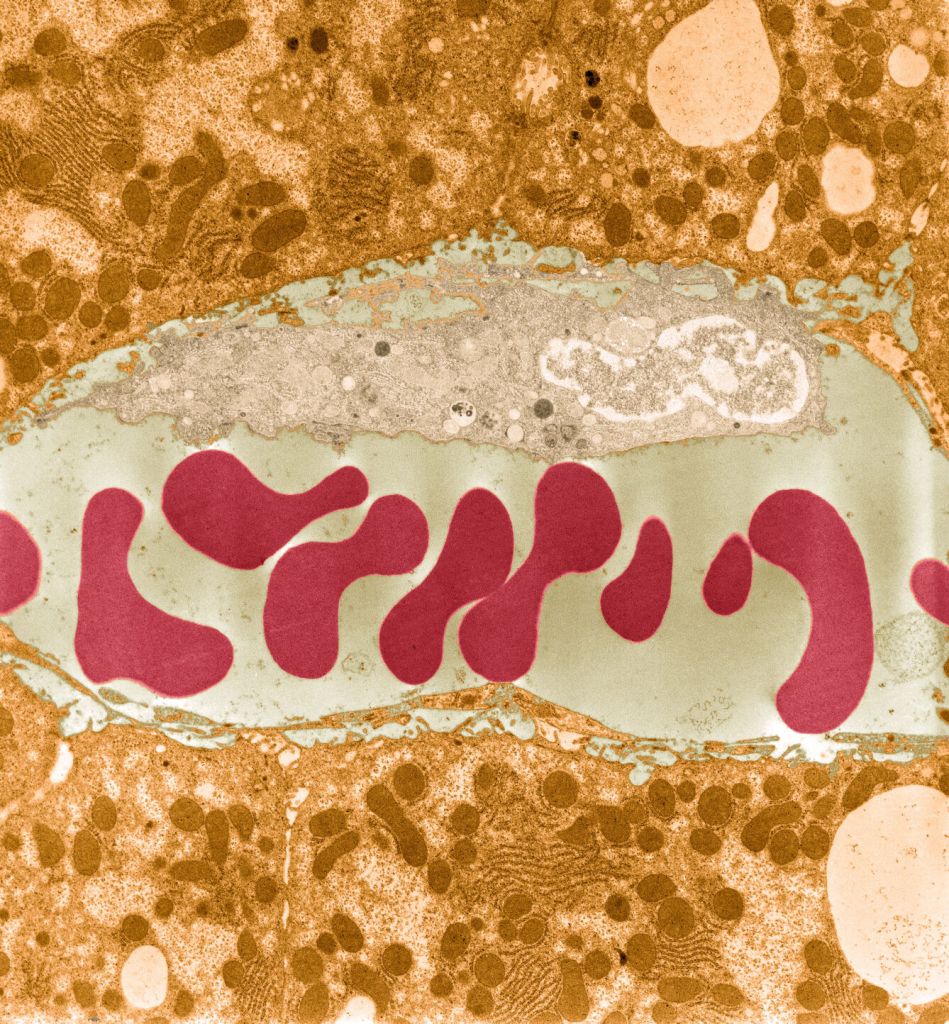

Image Credit: Blood vessel with red and white blood cells. University of Edinburgh. Source: Wellcome Collection.