In “The Vulnerable and the Political,” Estelle Ferrarese talks about the affinity between care and the management of vulnerability. Both become political as they pertain to individual and social bodies. “The distribution of care,” Ferrarese says, “depends on patterns of domination and historical organizations that may stem from the sedimentation of gendered roles…” (237). Social structures and cultural perceptions (re)produce sick or healthy bodies and who is in charge (of care) of those bodies.

When we put it that way, how and through which tools and narratives we look at the body gains the utmost importance. Such questions might reveal our blindness and silences and give us new ways of seeing and crafting possibilities. This was a lingering issue in my mind that I ended up designing the syllabus of the course I’m teaching this semester on reading and building critical vocabulary around the body. When we discussed Monica Ong’s Silent Anatomies in class, which addresses these questions through a visual and linguistic exchange between literature, art, and medicine, I realized that I could also carry the conversation here.

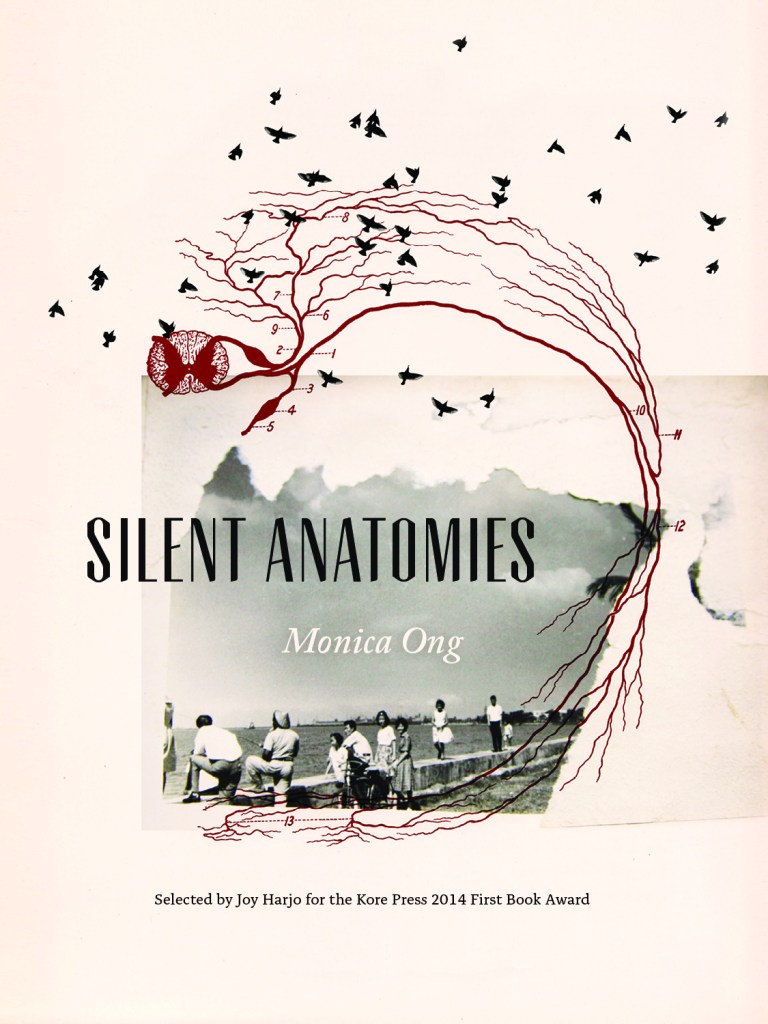

Silent Anatomies, selected for the Kore Press 2014 First Book Award and published in 2015, is a book of visual poetry. Ong, a visual poet, and Yale Library’s senior web and digital designer, decides to investigate her family history from China to Manila, Philippines, and then to the US, which cracks open some family secrets/silences over mental health, body shame, and cultural and linguistic barriers of health. An output of this journey, the book itself has a hybrid body composed of medical images, technologies, and objects with poems. Given that visuality and technology capture, (re)produce, disseminate, negotiate, and resist (bodily, affective, sensual, institutional, dominant) knowledge and power, Silent Anatomies unfolds vulnerabilities and how these are socially determined.

Silent Anatomies’ starting point is your desire to interrogate your family history and the silences it has kept. Could you talk more about it? How does your journey to China and the Philippines intersect with medicine?

Many of my projects begin with a steady line of inquiry. In this case, I also wanted to document whatever stories I could gather from elders and relatives while traveling to Asia with my parents. Many stories emerged in which cultural silences of the body were a throughline that connected the experiences of many people in my family across generations. Whether we are thinking about untranslated stories, under-reported, hidden by stigma, or other kinds of erasure, I became inspired to write about the social hierarchies that shape how the women in my family inhabit gender and how it informs our health-seeking habits from generation to generation.

Could you elaborate on the body’s cultural silence and how it relates to health?

I owe a debt of gratitude to my Aunt Juanita, or Ah-Ching, as I addressed her, for planting this seed of inquiry. She struggled with her mental health for most of her adult life, particularly with symptoms that indicated schizophrenia. Proper treatment, however, eluded her because to access care meant to admit to mental illness existing in the family bloodline. The stigma around mental illness kept her in the shadows with the fiction of supernatural powers as a way for relatives to keep from losing face. Her decline in health haunted me, and, in a sense, it was her ghost who coaxed me to keep writing about these silences so that the arts could open a space for honest conversation in my community about mental health.

Visuality is the key to this conversation. Most of my students commented on the book’s dynamic conversation between text and image and talked about the times they complemented one another. Do you agree with them? Do you think of some moments of tension and contestation; one speaks, and the other stays silent, perhaps?

One of the adventures in this project was to consider new alchemies for how text and image interact with one another, contributing to syntax and lyrical “heat” by way of bringing disparate elements together. I hope that the gaps or spaces between the elements are where readers can connect to the work with their own experiences. It is important to me that the elements do not echo one another but offer space for inquiry to occur in between.

Medical imaging technologies like ultrasound and CT scan create a surface for your poetry. What do you think about the affordances and legibility of such technologies, especially since they became a language and writing and designing tool for you?

I imagine that when people see visuals like this during doctor visits, it speaks to a deeply personal emotional space with high stakes and big questions. Inherent in this visual language is also a set of power dynamics and many unknowns to decipher. In this sense, it sets the reader up for an intimate, close reading, perhaps one that is slow, careful, and exploratory. At the same time, it is an invitation for a broader set of readers, another way in for those who have familiarity with how to “read” these diagrams, who then get to have an encounter with poetry.

We can talk about these informed readers a bit more. You attended the reading or discussion in medical settings, right? How was the response coming from the professionals? Have you had any encounters that surprised you?

I recall giving a reading at a Chinese cultural center in Tucson, Arizona, and meeting many elders in line afterward. Many were eager to tell me about their family secrets. One woman told me about how her family pretended that her brother had a cold when, in fact, he was dying from cancer. She called it “the C-word” as though saying the word “cancer” was forbidden. The public health physician who coordinated the talk with me then shared that in that particular county, the turnout for cancer screenings by demographic was the lowest among Asian Americans—as such, being able to participate in conversations like this from a cultural perspective created space for examining how cultural attitudes are connected to health-seeking habits in cultural communities

In narrative medicine, stories are employed to educate doctors and help them understand and empathize with the patient. You, however, do reverse and use medical imagery and vocabulary to understand your familial relations and history. In “Innervation,” you keep a diary of an intercoastal nerve on a family photo of a coastal space and call shame as communicans, which connect the intercostal nerves to the sympathetic trunk. Sympathy instantly transforms into a feeling that fails to connect family members: “We open up on each other’s walls. Sympathetic, /But never in the same room.” (35). What is so appealing in medical imagery that you’re convinced it can mediate your relationship with your family and give you a language to grasp it?

What I particularly enjoyed about making poems like this from anatomical diagrams is being able to open up the poem to a non-linear approach to reading. Every reader reads the poem differently because of how the words are arranged around the diagram, and with each reading, the poem takes on a new life. Likewise, in my own attempts to understand and navigate language and lineage with my family, it, too, is often fragmented, non-linear, and imperfect, but rather than trying to “get it right” as something aesthetically scientific might suggest, it is in the process of improvisation where we really learn from one another.

Could you open the term “aesthetically scientific”?

When I say “aesthetically scientific,” I refer to the way medical information is conveyed with the visual language of data, information design, and other elements that carry an air of factual authority. Likewise, when thinking about conventions of reading, there is a traditional notion that the author writes in a linear sequence that the reader understands to follow when engaging with the work, just as patients take doctor’s orders. While my work utilizes what appears to be authoritative visuals, the reading of diagrams opens up to non-linear exploration, allowing the reader and author to become collaborators of meaning and moving from the transaction of conveying data to personal but ambiguous space, moving us beyond the facts and into emotional landscapes and slippages.

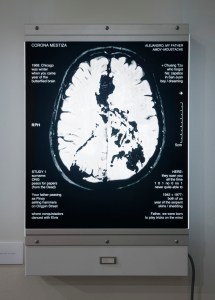

In “Corona Mestiza,” we see the image of a cross-sectional brain scan. Notes on the medical history of your family and your surname, as well as a mention of Chinese philosopher and poet Chuang Tzu, crosscut each other. Another striking thing is that the close observation of the scan showed that what appears to be lesions at first turns out to be a map of the Philippines. Could you walk us through this multi-layered visual poem?

This piece is a kind of portrait of my father, who I saw as a shape-shifter as he moved across many cultural spaces of identity as a son of a Chinese immigrant born in the Philippines who then started a new life in the United States. Although he lives comfortably in America, there is much in his mindset for which the Philippines is a touchstone of formative memories and a sense of home, which is referenced by the map. Our family’s Chinese name is Chuang, which we share with the great poet and Taoist teacher, but when my grandfather arrived in the Philippines during the war, he purchased the papers of a deceased person named Ong, which was the name my family lived under. Ong is still my legal name, but I also keep a Chinese name under Chuang. In this sense, our identities are quite layered and sometimes I think of my work as a way of documenting these less visible layers.

This is also shown in a medical light box, first, right? What was the process of carrying it to a two-dimensional surface?

When I designed this piece, I did produce it as a Duratrans print customized for a vintage medical light box. Having the piece backlit and mounted on the wall added the right visual context for a considered kind of reading.

“Etymology of an Untranslated Cervix” poses a question in relation to language and power in medicine. You have an epigraph from an article on cervical cancer in Uganda: “In Rufumbira, the local language here in Kisoro, there is no word for cervix, and the word vagina is a shameful, dirty word, rarely uttered.” Who is able to decide or put expression to our pain or needs?

You touch on exactly the essential question the poem seeks to ask. Language is powerful because it opens pathways of agency and power. It was important to put a critical eye on who gets to create, translate, and normalize language about women’s bodies, as a language not only penetrates the logistics of treatment but also affects policies, laws, and education that also impact health outcomes.

The visual component of the poem is arresting. A forest is placed on a cervix X-ray, where the uterus and vagina merge, and a helicopter hovers over the forest. On the one hand, I remember how Beatriz Colomina understand X-ray as “a kind of self-exposure… more intimate kind of portrait of oneself or someone close to you.” On the other hand, I think of the parallel development of military and medical technologies and how the aerial shot gives a sense of warfare. What was in your mind when you put this collage and poem together?

The scenario in my mind when creating the collage was thinking about a forest fire that one had no words to locate or convey to rescue teams. But to your point, yes, as artist Barbara Kruger once said, “Your body is a battleground.” The politics of the female body has always been a hot-button issue, especially in terms of who is in control.

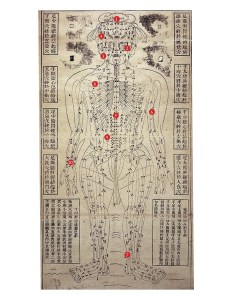

One of the most significant contrasts between Western and Asian medicine is shown in “Medica Visits the Witch Doctor.” The visit is described as a ceremony as if the patient and the witch doctor play a part in it despite the noticeable hierarchy between the two. Medica sounds out each body part with some wishes, regrets, and desires, as the acupuncture chart on the juxtaposed page illustrates. This differs from a doctor’s visit or treatment in the West. What does it say about our knowledge about/of the body and medical practice?

These impressions are based on how differently my relatives go about ideas of treatment. My father, who was a Western-trained doctor, often focused on gathering data points in his practice, looking for symptoms and patterns. At the same time, I had relatives who believed in spirits, Chinese remedies, and other practices, which sometimes had embedded cultural beliefs or folklore, often speaking to stories connected to various points in the body.

Did you compose the poem based on the chart or juxtapose them intuitively?

I made a list of points on the body that I associated with memory, superstition, or sensations as jumping-off points for lyrical play. Each point was a doorway that I would write into and just see what happens.

How does the book play out the relationship between cure and care?

It interrogates the question of what is being cured, whether the cultural anxieties these remedies seek to repair are constructs of our own making or the cost of collective forces acting on the body.

Silent Anatomies traveled in different forms, media, and space: in book format, as an exhibition, and spaces: in book format, as an exhibition, and as a town-sized project. We can almost say that you have built a community in different capacities and scales to unfurl cultural silence on the body, gender, and violence. Do you agree? Was that in your mind all along?

My approach to doing work is to go wherever the work asks me to go and design the best contexts for interaction, reading, and experience. While this started as literary objects, I am pleased to have challenged myself to design poetry across many formats and spaces because it has taught me so much about how differently people read, learn, and experience poetry. We may not always know where a project is going when we start, but I try to follow the questions and create an experience that will hold space for enriching conversation and encouragement for my readers.

Alongside Silent Anatomies, you traveled with some other projects, too. That would be great to hear about them. Do you have a long-standing or upcoming project? Will we see more medicine involved in your work?

During the last few years, I have been exhibiting Planetaria, an exhibition of visual poems that leverage the visual language of astronomy to explore the precarious territories of motherhood, women in science, and diaspora identity. I’m currently developing this into a reading for the planetarium, which will debut in March 2025. I’m also delighted to publish this work as a second collection of visual poetry by the same name, which will be due out next May. Science continues to be an important framework for inviting audiences from across disciplines to imagine new cosmographies where everyone belongs.

*I want to thank to my friend Jiaxin Yan, for introducing me to Silent Anatomies, and Monica Ong and Kore Press permitting us to reproduce the images from the book here.

Bibliography:

Colomina, Beatriz. X-Ray Architecture. Lars Müller Publishers, 2019.

Ferrarese, Estelle. “The Vulnerable and the Political: On the Seeming Impossibility of Thinking Vulnerability and the Political Together and Its Consequences“. Critical Horizons, Vol. 17 No. 2, May, 2016, 224–239.

Ong, Monica. Silent Anatomies. Kore Press, 2015.