Image Credit: “The Substance – Official Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by NEON, 14 February 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LNlrGhBpYjc.

In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), as Victor Frankenstein starts building a female companion for his monstrous creature, he realizes:

“…she might become ten thousand times more malignant than her mate and delight, for its own sake, in murder and wretchedness. He had sworn to quit the neighborhood of man and hide himself in deserts, but she had not; and she, who in all probability was to become a thinking and reasoning animal, might refuse to comply with a compact made before her creation” (125, my emphasis).

Worried that she won’t comply with the life he prescribes, he tears the “body” apart, gathers the pieces into a basket, dumps them in the ocean, and falls into a peaceful sleep on his boat until morning (130). I’ve always imagined something noncompliant in her momentary suspension in the water, fragmented, moving toward the seafloor. She escapes a consciousness filled with societal rejection and worse, a life created for the sole purpose of pleasing the male creature.

I think of this moment when I think of Lauren Berlant’s concept of “lateral agency,” a mode of existing “sideways” in interruptions from neoliberal demands of capital like labor, identity, and decision-making. For Berlant, lateral agency produces “episodic intermission from personality,” opportunities for “inhabiting agency differently in small vacations from the will itself, which is so often spent from the pressures of coordinating one’s pacing with the pace of the working day, including times of preparation and recovery from it” (799). Berlant focuses on eating as one of these opportunities, banal but important. “These pleasures,” they write, “can be seen as interrupting the liberal and capitalist subject called to consciousness, intentionality, and effective will” (799). Of course, this is far from Doctor Frankenstein’s dismantled corpse thrown into the sea. But they share a sense of unwilled escape and the paused velocity of suspension—of inhabiting an elsewhere of capitalism; imagining a type of noncompliance that doesn’t rely on active agency.

I was reminded of these suspensions while watching Coralie Fargeat’s most recent body horror film, “The Substance” (2024). In the film, aging celebrity Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) takes an off-market drug that causes her body to produce a “younger, more perfect version” of herself who calls herself “Sue” (Margaret Qualley).

Only one of the two selves can be conscious at once and they rotate on a seven day cycle. Critically, it is the user’s responsibility to perform an intravenous “switch” procedure on the seventh day. While the drug’s instructions emphasize that the two bodies are one person, there’s no shared consciousness—they understand each other as two separate people and they resent each other. Unsurprisingly, Sue starts to stretch her time beyond the seven days, with horrific consequences.

Blatant ageism aside, could the substance itself have offered something like Berlant’s lateral agency for both Elisabeth and Sue? An opportunity to exist otherwise, to interrupt life in “episodic” intervals, to pause the demands of personality, for one self to exist while another rests, suspended elsewhere? For it all to be a regular, mindless pace, the banality of a week? Could the film have made her self-medicating something empowering rather than desperate and pathetic? And could it have imagined her noncompliance with the drug’s prescribed directions as a meaningful opportunity for bending the rules rather than just locking her in an inevitable (deserved?) demise?

Rather than taking an opportunity to suspend herself elsewhere or otherwise, Elisabeth uses the “substance” to reinscribe herself into laboring society. She had been fired from her dance fitness television show, but Sue is immediately hired as her replacement. Sue centers her body’s capacity for labor as its—and her—ultimate value; redeeming Elisabeth’s failure. In a meeting with the network executive (Dennis Quaid), Sue says she’ll need every other week off for “taking care of [her] mother, who is very sick.” Her week as Elisabeth is cast as a disability disqualifying her from participating in labor’s mandate of production, an ideology that leads to the physical disabling of Elisabeth’s body.

Much of Elisabeth/Sue’s suffering comes from her/their decisions to ignore the rules of the drug. The film unsubtly blames society for pushing them to defy the directions, but it also casts medical compliance as a personal responsibility. In a medical context, “noncompliance” is typically used to describe “patients who do not follow health recommendations prescribed by their medical professionals” (Horowitz). “Some medical organizations,” writes Daniel Horowitz, “including the World Health Organization (WHO), believe that the term associates those who fail to follow treatment instructions as uneducated or willfully ignorant”—both implicitly the fault of the patient. While some health organizations advocate for language that might invoke less blame on the patient, accounting for “more varied reasons…that may be beyond their control,” the film seems to indict (and punish) Elisabeth/Sue for an active and willful noncompliance (Horowitz).

Blaming the user for noncompliance generally assumes total transparency, clarity, and comprehensibility from the drug’s packaging and prescriber. Elisabeth learns about the drug from a nurse who slips a zip drive and handwritten note saying “it changed my life” into her pocket—not exactly an official prescription. But the instructions and packaging for “the substance” are such a caricature of simplicity, it seems that it must be entirely her own fault for not complying. Her first instructions come from a video that uses saturated visuals of eggs and yellow putty to metaphorically represent the growth of one body out of the other and their ultimate self-sameness—made of the same yolk/clay. Like today’s pharmaceutical ads, there is no explanation of the chemical mechanism, or any science at all, really. The user doesn’t need to understand that part. The drug arrives designed for a social media “unboxing” video: upon opening the box she pulls out the first step for using the substance, beneath it the second and the third. The directions are written in huge bold text on large index cards, more aesthetically aligned with Nike than the FDA. The first card just has a 1 on it; beneath it a plastic-sealed serum and syringe labeled “ACTIVATOR.” Other devices are also minimally labeled: “STABILIZER OTHER SELF”, “FOOD MATRIX”, “FOOD OTHER SELF,” etc. Where there is text on the cards, its language is plain and simple: “YOU ACTIVATE ONLY ONCE”; “YOU STABILIZE EVERY DAY”; “YOU SWITCH EVERY SEVEN DAYS WITHOUT EXCEPTION”; “REMEMBER YOU ARE ONE”.

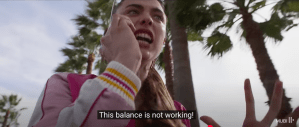

The last form of instruction she receives is from the drug’s telephone helpline. When both her and Sue call to complain about the other self’s “misuse” of the substance, they’re given curt, matter-of-fact answers from the same voice. Every call bypasses tangled networks of individuals, departments, and organizations that most people in the real world have to go through to get any kind of help in American healthcare. Here, the line is always available to parrot simple instructions: “respect the balance and there will be no more inconveniences”; “remember there is no ‘she’ and ‘you.’ You are one.”

It’s an excess of minimalism. As much as the film makes the instructions so clear that the viewer intuitively blames Elisabeth/Sue for not following them, it also lampoons a larger (official and unofficial) medical system that inadequately communicates with and educates its consumers. And while the film nods to the abuse of desperate individuals participating in free clinical trials (Elisabeth never pays for the drug) who aren’t given vital information, the characters’ whiteness, wealth, and other forms of privilege bar it from making any real acknowledgement of American medicine’s history of clinical exploitation of racialized and minoritized people.

Still, the film stops short of incriminating just medical and clinical discourse, showing that this same vague oversimplification is spread throughout modern consumer pedagogy. Both Elisabeth and Sue star in televised fitness programs. They lead complicated dance routines that viewers are ostensibly supposed to follow along. But Elisabeth only guides with quips, “You got it!” “Come on!” and Sue is mostly silent. There’s one clip of Sue teaching her backup dancers in rehearsal, talking through the choreography. But consumers don’t get that comprehensiveness and comprehensibility.

Loud and grotesque, “The Substance” centers misogyny, consumerism, and the centripetal vortex of capitalism’s demands on (re)productive labor. It shatters the possibility of suspension: both Elisabeth’s and Sue’s weeks ‘off’ are stages for sabotage, not rest. They create new responsibilities, decisions, and horrors—a world where even the banal retreat of eating becomes an explosive performance of revenge. Running through this more quietly is a set of questions on contemporary communication and pedagogy: on how simplicity fails consumers while investing them with blame. Regardless of who the film ‘blames’ most though, Elisabeth/Sue’s body suffers until it, like the female flesh Victor Frankenstein abandons, loses its legibility as a body, disarticulated and forgotten.

Works Cited

Berlant, Lauren. “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency).” Critical Inquiry, vol. 33, no. 4, 2007, pp. 754–80. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/521568. Accessed 23 Feb. 2025.

Fargeat, Coralie,, et al. The Substance MUBI, 2025.

Horowitz, Daniel. “Compliance (Medicine).” Salem Press Encyclopedia of Health, Jan. 2025. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=680451aa-ffd5-3330-a400-a348f6d5498c.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Nick Groom. Frankenstein: Or, The Modern Prometheus: The 1818 Text. OUP Oxford, 2018. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=2245822&site=ehost-live&scope=site.